Enos Nyamor visited "We Are Each Other" in Atlanta focused on the Clark's community-centric and participatory projects.

Sonya Clark, Detail of Madam C.J. Walker. Photo: Grid_o2. Courtesy of High Museum of Art.

US-American artist Sonya Clark’s vigorous vision is dominated by fabric, wool, human hair, silk, and beads. These are the conduits to Clark’s world of textiles – and what is a textile but an extraordinary phenomenon of connections fabricated by the repetitive and absorbing acts of weaving, of alternating series of warps and wefts, of fingers and hands rotating in patterns? Bonds are the recurring element of her practice, activated in community engagements, performances, and interactions. At the High Museum in Atlanta, Georgia, viewers are confronted with an acute awareness of bonds in the presence of grievances through a panoramic survey exhibition of Clark’s work, titled We Are Each Other and on view through 18 February.

Consider the iconic Gele Kente Flag (1995), displayed in the second hall in a circuit of compartments that each offer a distinct phase in her artistic expression. Presented initially as part of Clark’s thesis at Cranbrook Academy of Art, the head wrap designed out of pieces of the Star-Spangled banner and Kente fabric is indicative of her career-long exploration of the nexus between identity and representation. While its materiality articulates national symbols, its title is a blend of Asante, Yoruba, and English, suggesting a complementary representation of African identity in the US.

Sonya Clark, The Beaded Prayers Project, Installation view at Newark Museum. Courtesy of High Museum of Art.

In extension, Beaded Prayers (1998–ongoing), gathers buttons, beads, pins, cowrie shells, silk, and fabric through a participatory project. Grounded in the acts of knitting and weaving, of encircling, wringing, whispering, and kneading, it is a collection of messages and desires inserted into pouches, which are in turn arranged on panels of an earthy brown that create an immediately stimulating visual experience. These sequential actions are ingredients for rituals to thrive, movements planted into memory, in specific format, almost without alteration; accompanying words follow closely, hinged to a structure. Like rituals, the project reflects bonds fabricated, negotiated, and ultimately shared. The communal amulets themselves, dissolving in some broad effect of light in their grid, all equally blended, balanced, heightened, and not easily detached, radiate a beam of tenderness over little objects.

Sonya Clark, Hair Craft Project, Hairstyles with sonya. Photo: Grid_o2. Courtesy of High Museum of Art.

In Clark’s Hair Craft Project, here shown as the Hairstylists with Sonya (2014) and Hairstyles on Canvas (2013), the essence of human hair as a manufactured material – as a sum of ancestry, and therefore a result of a complicated natural identity-manufacturing process – lingers. In Hairstylists with Sonya, color photographs of hairdressers whose faces, asymmetrically arranged beside the intricate hairstyles that are the output of their hands, appear to fade into the glaring, vivid backgrounds. We see faces but not hands, yet there is a direct bond between tarsal and cranial. What minds fail to grasp might be encoded in fingers that memorize the patterns that are transplanted onto heads as astonishing hairstyles created from gravity-defying kinky hair.

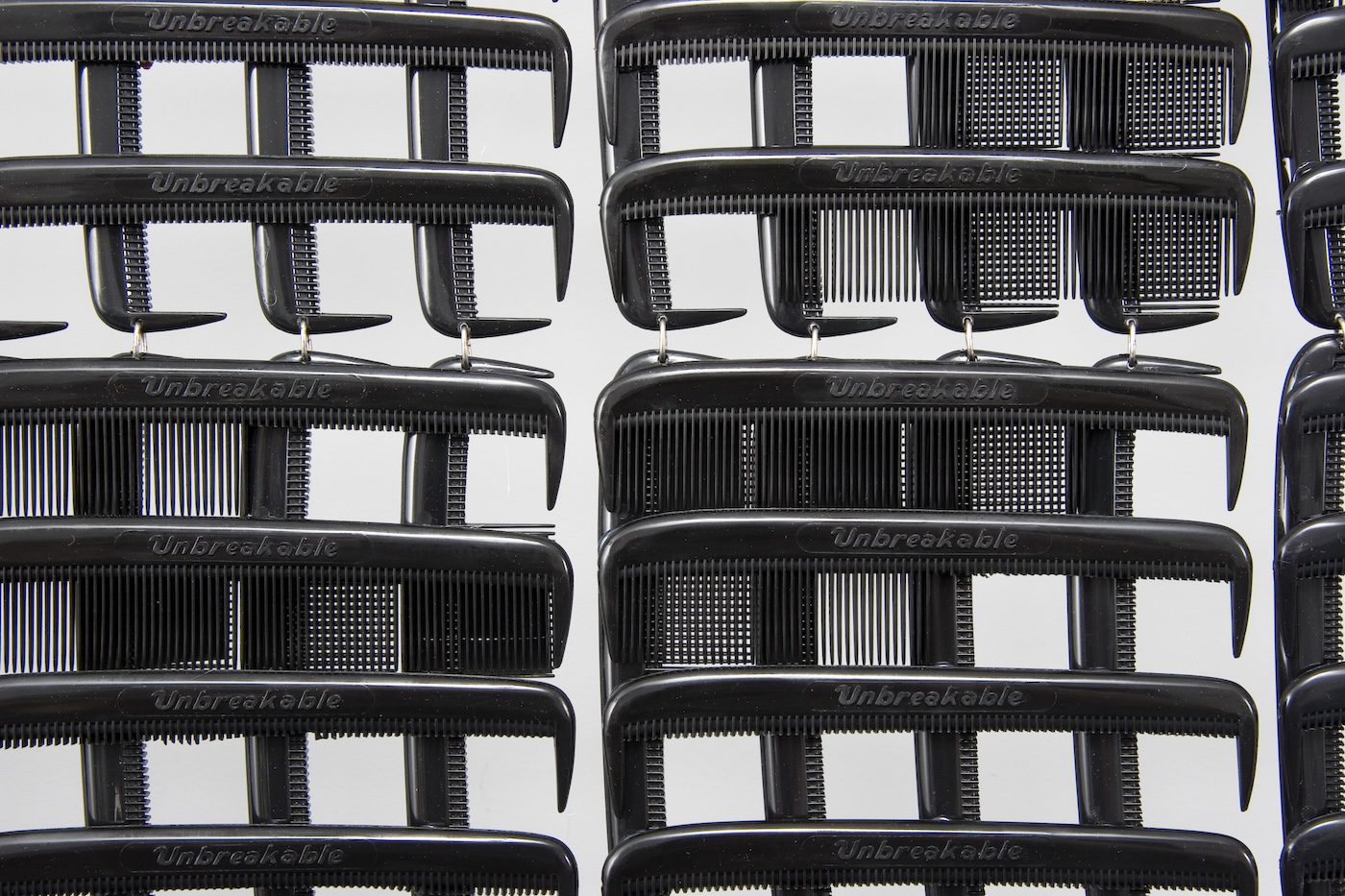

Sonya Clark, Madam C.J. Walker. Photo: Grid_o2. Courtesy of High Museum of Art.

Deploying combs as clues to achieving a particular hairstyle, but also as the item said to have produced the first self-made female millionaire in the US, Clark creates incandescent, flashing images that can only be momentarily captured. Black plastic combs are modified, through the selective removal of tines, and then arranged either vertically or horizontally to produce an image visible when observed from a distance – here the entrepreneur and activist Madam C. J. Walker (2008). The dark tones around the eye sockets suggest a pensive atmosphere; they inspire a sensation of eyes not looking just right. Other remarkable pieces in this series include the abstract Whole Hole and Hole Whole (both 2015).

Clark’s examination of African diasporic identities reaches a new level of articulation in We Are (2023), a translation of Gwendolyn Brooks’ poem Paul Robeson into video, inserted as a virtual nook in the exhibition space. As the performer Jennifer Harge rises and collapses, we are serenaded with verses. The background is powdered with fog. Challenging the natural law that governs falling bodies, the dancer is dressed in a woven fabric that codifies strangeness, making more extensive the poem’s emotional depth, its language of involuntary migration. Prolonged movements are captured in a series of oscillations which take time to subside; we experience the poem transformed into a longing that no movement can assuage.

Bonds are especially relevant when threats loom, and these are never too far off in the US-American South. The Confederate flag is still a contested symbol: one side claims that it is part of their heritage, yet it represents subjugation, humiliation, and shame. From this contradiction sprouts the interactive Unravelling (2015–ongoing), a community-led performance in which harmony is sought in the deconstruction of a Confederate flag – a subversive act of creating new bonds by breaking inadmissible existing connections forged through alienation.

Sonya Clark, Unraveling, Performance view. Photo: Grid_o2. Courtesy of High Museum of Art.

Directly related to Unravelling comes Reversals (2019), a video showing Clark’s performance that year at the Fabric Workshop and Museum. Dressed in a purified sacred garment, Clark uses a drenched replica of the notorious flag to scrub a floor dirtied with dust from Philadelphia’s Independence Hall and Declaration House; her endlessly futile process reveals a passage from the Preamble to the Declaration of Independence. The garment Clark wears is a replica of the dress worn by Black female custodian Ella Watson in Gordon Parks’ American Gothic, a 1942 photograph of Watson with a broom and mop in front of a giant US flag, its stripes spreading like swamp mist.

One of the most persistent questions in Sonya Clark’s practice concerns the shape and colors of the US flag. She unrelentingly searches for harmonic connection in the US, a nation that is a tapestry of identities, while also darting a critical eye towards the superficiality of social interactions – especially in the South, where a sharp contrast exists between actions and the realities that they obfuscate. She points at bonds that are meant to be severed, in relation to those that are to be strengthened and nourished. But her work is also many other things, all bound to an enormous spiritual energy. Such an art practice is an expression of hope, and since it is prompted by imperfection, it is melted into a kind of radiance that is not likely to arouse tension.

Enos Nyamor is a writer and journalist from Nairobi, Kenya. He works as an independent cultural journalist, with a background in information systems and technology. Currently he is based between New York and Atlanta.

INVENTING YOUR OWN GAME

FEMALE PIONEERS

More Editorial