Zohra Opoku: Empowering Children of Color to Love Themselves

In the run-up to our new edition, we spoke to the artist about her passion for fabric and photography, her childhood, and how her new work came about.

Julia Grosse: You just had a solo show in Dakar at Raw Material Company called WITH EVERY FIBER OF (MY) BEING, and I liked this detail in the press release: “Like a jigsaw puzzle, she recomposes her personal history, interweaving pieces of traditional fabric with family archives collected and engraved or silk-screened on canvas.” Why does physically working with fabric have such an impact on your practice?

Zohra Opoku: In most instances it is fundamental in my practice. Parts of my work explore the ability to express one’s identity, and identity can be actualized through textile. It brings me satisfaction to handle a piece of cloth and discover it from different perspectives – like how its textures have conversations with the imprint of the image, how its history and age add to the narrative of the work, and how its origin and type can influence a particular aesthetic of expression.

I have grown so comfortable with the marriage between my use of fabric and my use of photography that my subconscious mind is longing to recreate certain prints I from earlier phases of my practice. I spent a lot of time in the darkroom at the beginning of my art education, and right now I admire those developed images in particular. Because they were still in black and white, they remind me of photographs of my childhood. Surveying them, I travel to fleeting moments of my past and feel nostalgic as I work with new mediums. Recently I have introduced colors, making the entire process much more complex – I consider fabric dying and colors in a very meticulous way. I have further developed into a very large-scale screen-printing and alternative photo processes where I print onto textiles. This allows me to wholly connect my interest fields across mediums and ideas. As I screen print images onto fabric, the material literally absorbs the photographic image, reflecting how material can become imbued with meaning, memories, and history in society.

Installation View of „Zohra Opoku: With Every Fibre Of (My) Being“ at Raw Material Company, OFF Biennale Dakar, 2024. Photo: Delphine Buysse. Courtesy of RAW Material Company.

JG: You completed a degree in fashion at Hamburg’s University of Applied Sciences and briefly worked in fashion design. Why did you decide to shift your practice into visual art?

ZO: I studied both: fashion design and photography. And my exploration in fashion wasn’t brief. Initially I was focused and determined to become a fashion designer. I had the chance to work for almost ten years in exciting places in the industry as a stylist, designer, and creating marvelous window installations. I have never been fulfilled by the role fashion plays in society – it’s seen as a business more than a deep reflection of cultural development – yet for me it has such transformative power. As one of the most accessible forms of self-identification, it became my research starting point for my artworks. My practice explores the ability to direct self-identity, and textiles are the perfect vehicle for identity formation. My work with fabrics evolved naturally into a studio art practice and once I started printing I realized textile would always be a central medium in my work. It was a logical development, it all happened organically.

<p>

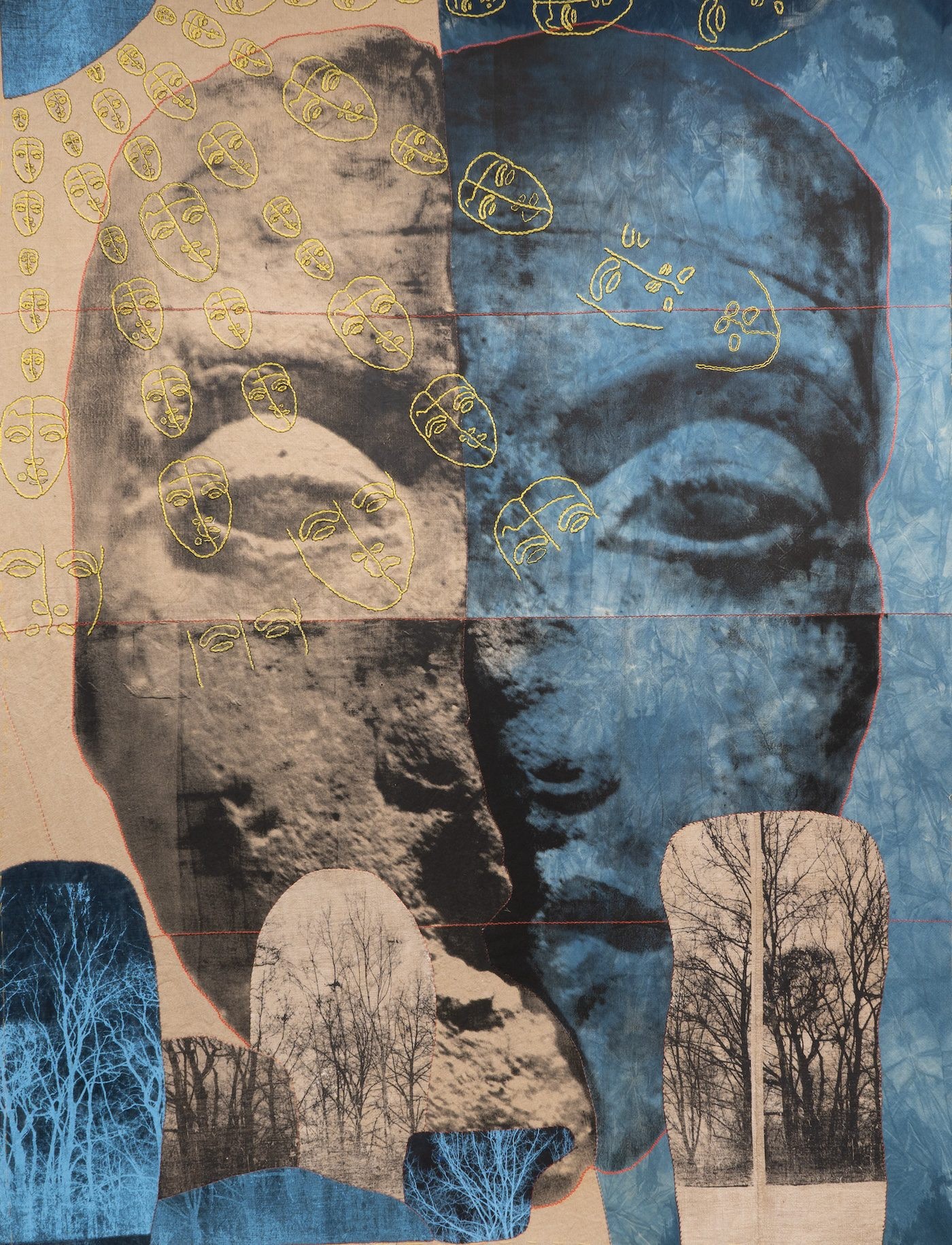

Zohra Opoku, ‘My head shall not be taken from me…’ [Extract from Chapter 43: Spell for ‘Not letting the head’ / An Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead/ The Papyrus of Sobekmose], 2024. Screenprint on linen, screenprint applications, hand embroidery, hand stitched. Courtesy of the artist and Mariane Ibrahim (Chicago, Paris, Mexico City)

JG: Your practice is always linked to aspects of your biography. Why is that important for you?</p>

ZO: It is processing and finally embracing the circumstances I was placed in. My Ghanaian father and my East German mother met in the summer of 1975 in Halle in the former East Germany (GDR) where they both were studying. I was born one year later. We were located behind the massive Berlin Wall of Communist East Germany. My father had to leave the GDR and return to Ghana when I was not even born. My mother could not follow and was left behind as a young mother. This became the remarkable story of my life. It has influenced my whole being, and my decision to become an artist and to explore belonging and identity.

Workshop with Zohra Opoku (right) and children. Courtesy of the artist.

JG: Tell me about your new ongoing work Give Me Back My Black Dolls. How did it start?

ZO: It was an idea I carried for a long time… I had a desire to put it into a meaningful and intentional process to be shared and to serve as inspiration. I do know that there are so many children of color or minorities living in places where it is quite difficult to relate to their environment and have trouble with belonging and connecting. On the other hand I observe how Ghanaian children have an inclination towards Westernized consumption as the Ghanaian government imports products and garments from other continents instead of promoting local makers and materials. This influx and reliance upon imported goods makes it harder for children to identify with their home culture. As a mixed-race child born in a Communist society, I collected some interesting related memories myself.

Contemplating the toys and dolls of my upbringing, I also brought in an 1845 German children’s book, Der Struwwelpeter by Heinrich Hoffmann, which had one story that was encouraging and empowering for me as a mixed-race child growing up in the 1980s in the then-GDR. When I identified myself with the little Black boy, I didn’t quite understand that the story was actually meant for the white boys teasing him and getting punished for it.

Dolls from workshop with Zohra Opoku and children. Courtesy of the artist.

The new body of work explores how consumption and mass media images in childhood can be detrimental to the identity of brown and Black children, which inevitably translates into adulthood. Through my experiences as a young girl and woman on my journey of empowerment, I have learnt to embrace myself, my skin tone, hair, and my body features. Through research, workshops with children, and collaboration with other artists, this project will materialize as an exhibition and eventually a publication that explores the roles of local and foreign dolls in shaping children’s identity, dreams, and visions.

JG: We’re thrilled that you are producing the next C& artist’s edition. Could you give our readers a hint about it?

ZO: The edition is a print collage titled Give Me Back My Black Dolls. It features a portrait of me as a child and serves as a first encounter with the visual composition of my new body of work of the same title, a quote from the poem “Limbé” by Négritude poet Léon-Gontran Damas. These works connect to my mission to encourage children of color to love and embrace themselves.

In the portrait I am two or three years old and stand in one of my favorite childhood places, the farm of my grandparents in Spreewald, which connects me to the most incredible memories before I started school in northern East Germany, where my mother moved to start her first job. The connection to nature, farming, and animals, as well as the familiarity of family handcrafts like knitting, crochet, embroidery, and sewing were strong there. I am wearing my grandfather’s garden boots. He was my hero in so many ways – I rarely left his side. Today I understand that when my identity started to get defined in my early years, everything was about that place. The shift and difficulties started with school when bullying, beauty ideals, and later puberty became daily challenges.

Zohra Opoku, 2024. Photo: So Fraiche Media. Courtesy of the artist.

The drawings featured in the edition are by my son Junior, who turns 20 this year. I have been making choices for him to be able to grow a strong mind as an African child, knowing who is and where he is coming from. Drawings featuring things he saw in our family home, a reality he was authentically living, and I love this for him – going out into this world very conscious of himself, his Ghanaian heritage, and the beauty and power of his Blackness.

Zohra Opoku (b.1976, German and Ghanaian; lives and works in Accra, Ghana) is internationally recognized for her work with textile materials and the interweaving of historical and personal themes, particularly in the context of contemporary Ghana. Her work is collected by renowned institutions such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Tate Modern and most recently The Centre Pompidou.

Julia Grosse is co-founder and artistic director of the platform Contemporary And (C&). She is a lecturer at the Institute for Art in Context at the University of the Arts in Berlin and Strategic Advisor at the Gropius Bau. Grosse studied art history and worked as a columnist and arts journalist in London. She has written and co-edited several books and in 2020 was (together with Yvette Mutumba) winner of the prize “European Cultural Manager of the Year”. In 2023 she curated John Akomfrah’s first big institutional exhibition in Germany, “John Akomfrah. A Space of Empathy”.

Learn more about the C& Artists’ Editionshere.

C& Artists’ Edition

C& Artists’ Editions #5 Zohra Opoku

Out Now! C& Artists’ Editions #4: Agnes Waruguru

Beyond What We See. Once Upon a Time, Once Upon a Future

Textile

C& Artists’ Editions #5 Zohra Opoku

Hamid Zénati. All-Over