Absent Figures: The Difficult Questions Restitution Raises

Being asked to call something an object can be troubling, as evidenced in Invisible Inventories, an exhibition at Nairobi National Museum that raises questions about looted Kenyan artifacts. Awuor Onyango guides us through the exhibition and its conception to make visible the certainties and uncertainties within the current phase of decolonial action.

At the Invisible Inventories exhibition opening, I’m handed a tote bag marked “ARE WE STILL PROTESTING THIS SH*T?” and an 86-page zine detailing some of the academic research and imaginings undertaken by the International Inventories Program (IIP). The databases of the 32,501 Kenyan objects identified across thirty European and North American collections thanks to the IIP’s two-year research project are not available to the public, but the exhibition hopes to open up exploration of their findings despite this bureaucratic setback.

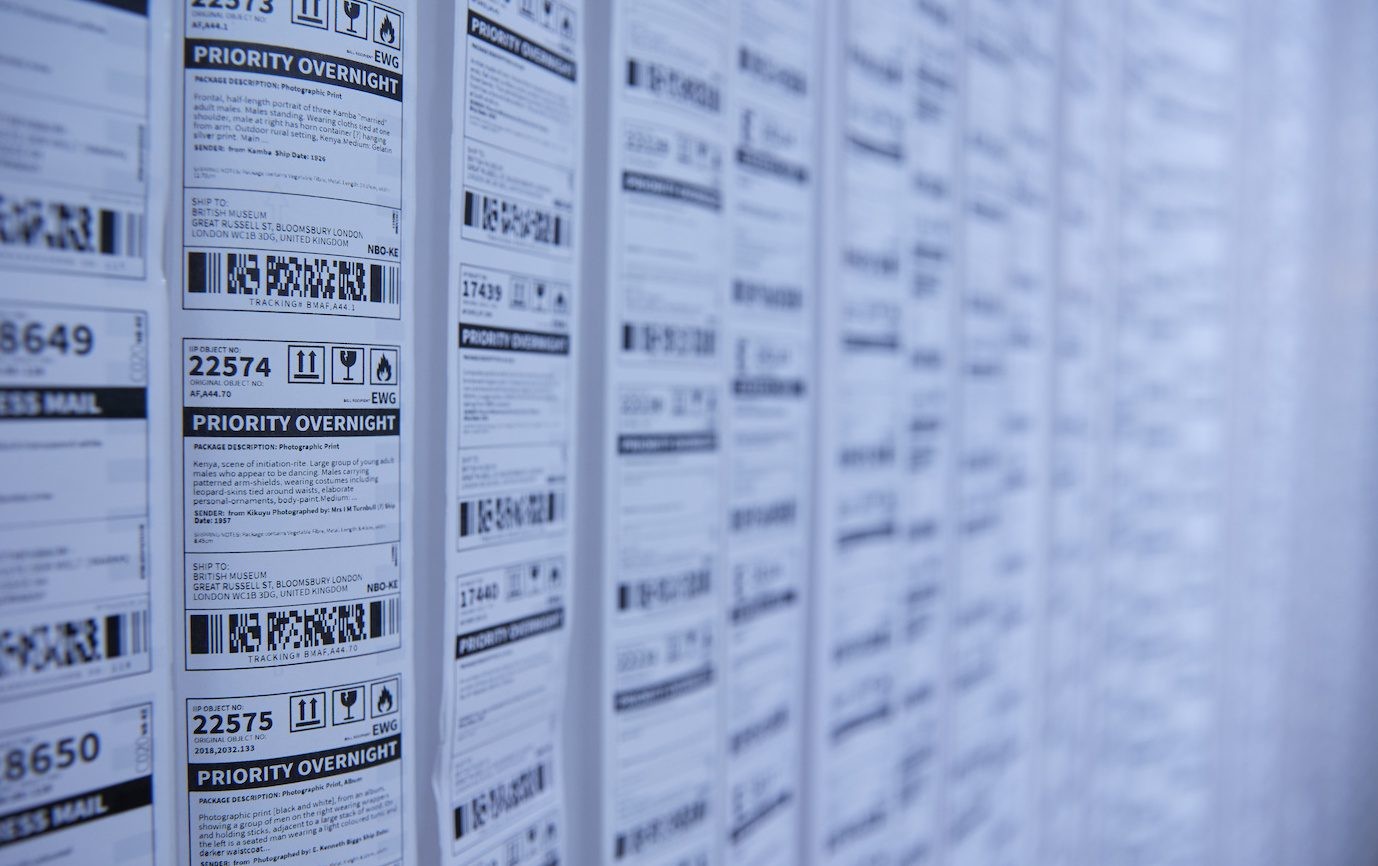

Either side of the exhibition space are curtains of paper swinging softly in the wind – shipping labels. Each label reports the object’s place in the database under “IIP Object Number,” a package description identifying what the object is, some “anthropological” notes, sender information, date sent, and delivery address providing a glimpse into the database and a horrifying estimation of exactly what we know to have been lost.

[cand-gallery image-no=1]

“The extraction was a massive project,” says Jim Chuchu of the Nest Collective, a Nairobi-based artist collective that’s been part of the project since its inception in 2017. Jim points out that due to space restrictions the shipping labels on the walls represent just about 2000 of the 32,501 items identified.

IIP Object 17742 reads: “Arrowhead (with Clan marks) made of wood. See-’Wat’ Clan Marks. These sticks which have papers round them were given me by the Bwana_ and procured by him from Magarini or Marafa. The names in Arabic character on the labels.”

I quickly realize the tote bag is too small to carry the rage triggered in me by the curtains of shipping labels, especially when I find that some have the objects blurred out, a compromise between IIP and museums that refused permission for these objects to be publicly named.

[cand-gallery image-no=2]

You can spend an entire afternoon looking through the labels, each a small crime-scene report relating not just to an object but to part of a dying spiritual tradition or design culture – dying because it is denied and made unavailable to a living people. Imperial, colonial, and other violence has dispossessed people of their meaning-making mythologies, philosophies, sins, and successes, replacing them with internalized colonial propaganda about their communities’ ideas of the world. Where do we even start to reckon with the shame and loss of the unknown, the banned, the made taboo, the stripped away, the repurposed in order to be more palatable? In the exhibition, Western institutions’ refusal to see these as losses for living people is emphasized by a row of empty museum displays with stickers by the side; altars to the absence of phantom objects.

“The thing about absence is you can feel it, you can see the corners and the boundaries, of it but you don’t know what the absence is,” Jim Chuchu says of the void that the lost ecosystems and cultures the missing objects represent, beyond the objects’ status as tangible entities.

It was impossible to borrow any of these objects for the exhibition, but the Nairobi-based Tuzi Collective offers another compromise. A few surreal collages further ground some of the objects, what they might have looked like while in use, who might’ve owned them.

[cand-gallery image-no=3]

“The tragedy is not that the objects aren’t here, the tragedy is that the knowledge systems and the cultures and belief systems that produce those objects don’t exist in the same way they did,” says Sam Hopkins of the Germany-based Shift Collective. “And they were demeaned, degraded and demolished in some cases, under a colonial system.”

Why can’t it be both? I quietly murmur.

For many communities across Kenya the tragedy is that the objects aren’t there, and that being expected to call them objects is difficult in itself. The Pokomo drum (the Ngadji) represents the Pokomo god’s voice. The head of a spiritual leader of the Nandi (Koitalel Arap Samoei) is part of his human remains, and his soul cannot rest without the proper burial rituals that require its return. The totemic tethers of dead family members of the Mijikenda (Vigango) were intended to continue the lives of the deceased and their association with the family, creating a family tree as well as facilitating the protection and prosperity of the living. Even those that are simply objects hold narratives, as Jim Chuchu says – tobacco pipes for women, for example, tell us something about what Kenyan women did for leisure, a narrative stripped from them by colonial torture camps and postcolonial nation-building.

[cand-gallery image-no=4]

“It is objects that should be home but aren’t, it is objects that are special, it is objects that are rare, it is objects that were taken under specific violent duress such as spoils of war,” Njoki Ngumi says of the objects in the database. “It is objects that have very deep significance to the people, and it’s very difficult to call these items, like human remains…”

Vigango tethers can be found in “Swahili-inspired” boutique hotels as well as in museums, the violence of seizing the remains of Black people’s souls and displaying them as aesthetics completely missed by their collectors. The exhibition presents profiles of some collectors, such as Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, CBE, DSO – the man who invited Nandi resistance leader Koitalel Arap Samoei over for negotiations and then beheaded him, sending his head to London to be “studied.” Louis Seymour Bazzet Leakey was the most surprising to me – a radical revision of his history is presented in the same space where a national auditorium is named after him. And then there was W.J. Ansorge, writer of a book called Under the African sun; a description of native races in Uganda, sporting adventures and other experiences (1899).

[cand-gallery image-no=5]

“He never wrote this book for a universe where the descendants of the people he’s talking about would read it,” Njoki Ngumi says of Ansorge. “So it was really important for us as practitioners, who come from the place he derided while being ferried around in his little racist travel-influencer carriage, and whose ancestors he was saying all these ugly and unrepentant things about, to take the right to say what we want as well. While we’re still on that land, and there’s still access to that vile book, we should say what there is to say about him with all of the honesty that we can.”

Discourse on restitution is full of reasons why these objects shouldn’t be returned, aren’t necessary, aren’t wanted back badly enough, won’t be properly preserved – full of attempts to shoo away the void or repurpose it as necessary for creativity. One of the Shift Collective’s contributions to the exhibition, a topography of loss, is a Kanga, a Swahili cloth made for women, whose feature design is inspired by the hand-cut depressions in which Kenyan objects are stored in museums abroad. The message on the Kanga reads “Anadaiwa hata kope si zake” (That person is so deep in debt even their eyeashes are not their own).

[cand-gallery image-no=6]

“The way that we look at the objects changes, so they become evidence,” Simon Rittmeier of Shift Collective says of those stored in German cultural institutions. The language of “objects” is an obfuscating one: in this context nothing was ever simply that – even a piece of cloth could be rendered totemic depending on who gifted it and what message it carried. Restitution isn’t just returning objects, relearning cultural identities, reshaping voids, loss, shame, and violences, it is re-engaging with what’s possible.

“For me, African art, yes there’s art that sits on canvas and on sculpture, but then there’s also art that sits on people’s bodies, the things that people eat, things that people dance to, things that people say about themselves,” says Jim Chuchu. “A way in which we apply art to our body which contemporary societies have lost touch with, so we now look at art as being separate from the body. Perhaps we can move back towards bringing art and life together again, not separating them into a kind of industry for purchasing and trading.”

Awuor Onyango is a writer and visual artist who lives in the pagan citadel of Nairobi in neocolonial Kenya. She explores ways of storytelling in the East African tradition of lived art. Her writing leans toward the Afro-surreal, AfroSciFi, and Afro-speculative and has been published in various magazines. In 2017, she was longlisted for the Caine Prize.

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission