The biennial explores the links between various art forms and makes way for visual narratives that challenge established storytelling.

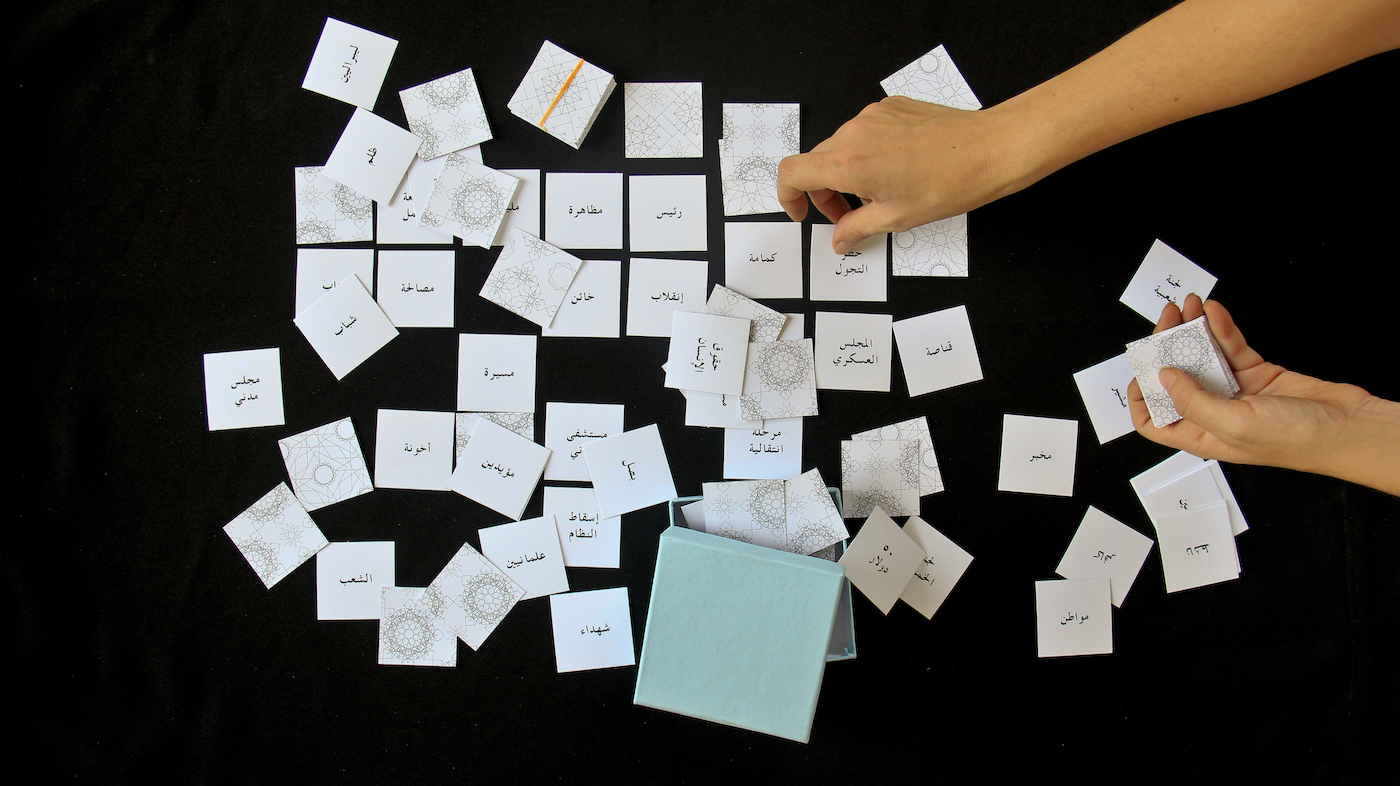

Amira Hanafi, A dictionary of the revolution. Vocabulary box (2014). Courtesy the Artist.

Titled The Words Create Images and running from November 17 to December 17, the 5th Casablanca International Biennale explores fields of text, words, signs, and language. Many of its works approach colonial linguistic legacies in Africa, asking how language influences thought systems and, by extension, discourses and interpretations of artworks, in both its material and metaphorical senses.

Curated by the Cameroonian art historian and critic Christine Eyene with assistance from Selma Naguib (Morocco), Patrick Nzazi Kaima (Democratic Republic of Congo), Onana Amougui Juste Constant (Cameroon), and Jacques-Antoine Gannat (France), the biennial is characterized by artworks that are conceptually and visually stimulating.

Large-scale exaggerated Black figures by Moroccan artist Khadija Tnana at the BIC Project Space hang loosely on transparent material. Swaying gently in the lobby, they point to discrimination and its attendant issues as hands painted in red pop out in a bid to offer support, which the figures appear to reject. The painted figures, according to the artist, represent an enslaved woman she knew when growing up. She recalls the woman being isolated, always working and unable to fraternize with others. Tnana poetically confronts her audience with her presence, which is coded with traits of isolation, discrimination, and marginalization.

Also present at the BIC Project Space are pictures by Moroccan photographer Ziad Naitaddi documenting people’s lives through a movie-like research process. They take the form of a docufiction reflecting Naitaddi’s personal perceptions and beliefs: through a film-strip technique with images accompanied by texts, he presents images that he identifies with both emotionally and physically.

Reproductions of African Writers Series book covers and slideshow with photographs by George Hallett. Courtesy of BIC.

At the American Arts Center, three sections offer photography/video art, performance, and mixed-media works that cross-examine prevailing art practices, historical awareness, and various discourses that surround these topics. Other works either explore language as a conversational form or knowledge systems, and there is an immersive display of over thirty reproductions of covers from the African Writers Series, the Heinemann book series for which the late George Hallett made photographs starting in 1971. An accompanying book, published in 2006 (Wits University Press), contains more than 100 of his black-and-white portraits of writers from Africa, in particular South Africa. Its chronological order helps us see the changing conditions and roles of writers from the 1960s to the present.

Queer activist and artist Brandon Gercara shows works emphasizing the undercurrents of domination in a postcolonial context. They are directly related to the sexual diversity and multiplicity of genders with which people in the Indian Ocean Island of La Reunion identify. Gercara translated these ideas into a performance, creating a situation in which spectators have a heightened experience of their own gendered bodies. These bodies are confronted with sound, performative actions, video, and objects that mediate identification.

Brandon Gercara, Lip sync of thought. Installation view at Biennale Internationale de Casablanca, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

With a deep interest in sculpture and the inherent performativity of archives and memories, South African photographer Lebohang Kganye’s black-and-white photos at the So Art Gallery investigate the illusory history of so-called “keepers of light,” merging fictional characters with real ones and thereby inventing new histores. As in the work of US-American artist Kara Walker, these characters are presented as cardboard cut-outs and stand on their own. They are flooded with light to cast theatrical shadows, inviting visitors to walk in and interact with each scene.

Inspired by the Malian photographer Seydou Keïta, the US-American artist Aisha Jemila Daniels has madeportraits of people wearing vibrant patterns and traditional garb including headgear. They reveal a groove of emotional dynamics through how they interrelate jointly and severally, showing unity in the diversity of visual and cultural resemblances.

Conversations, dialogues, and workshops have taken place in various locations, including the Musée de la Fondation Abderrahman Slaoui, the American Arts Center, So Art Gallery, and BIC Project Space. Topics included “The Notions of Nomadism, Displacement, Diasporic Experiences and Cultural Crossings,” “Art Writing in Africa,” “Research, Formats and Collaborative Practices in Biennials in Africa and Around the World,” and “Language of Change.”

The Words Create Images offers various possibilities for scrutinizing the past and thus for facing the present. It has about it a ray of optimism – one especially relevant for up and coming biennials that are in the process of carving a niche for themselves in the ever-growing world of art.

Bamako and Dakar biennials have attracted huge attention in recent years due to a combination of factors, including curatorial teams from diverse countries. They have helped open up space for art festivals. Casablanca’s biennial has been presented with consistency – with an exeception of a break owing to the pandemic – and since moving into gallery spaces in various parts of the city it has created wide public involvement. It has also engaged in diverse events in between biennials. These signs point to a bright future.

The 5th International Biennale of Casablanca takes place in two stages, with exhibitions and events from 17 November to 17 December 2022 and from 9 February to 11 March 2023.

John Owoo is an English and French-speaking journalist from Ghana.

GIVING BACK TO THE CONTINENT

More Editorial