Amandine Nana has opened a mobile cultural space that engages with Black art practices in contemporary and historical contexts.

Monika E. Kazi, Performance, Transplantation Gallery space in Montparnasse, before the exhibition hanging of "Sentiments Grandissant", August 2020

It is 1940s Paris and the neighborhood of Montparnasse is bustling with serendipitous meet-ups and conversations between artists that will seed movements yet to come. Some will be more remembered than others – specifically the white European male painters. But Beauford Delaney, Wilfredo Lam, and Gérard Sekoto were just a few of the Black artists who shaped the cultural landscape of this time.

In the essay “Moments of of A Shared History, African Artists in Paris 1944–1968,” art historian Maureen Murphy sheds light on this time: “Many of the artists who congregated in the city were labeled the ‘School of Paris’, a title that attempted to unify the diversity of their contributions and valorize the city’s identity. Artists from the colonial world, however, were not included in this category, even if their presence was undeniable.” The seminal journal Présence africaine was founded in Paris in 1947, and in 1957 organized the first Congress of Black Writers and Artists that convened writers such as Frantz Fanon, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Aimé Césaire, and Jacques Stephen Alexis, who discussed the place of their work in a world delimited by solely Eurocentric perspectives.

Massabielle Brun, Fanny Irina and Yanma, winners of the Transplantation residency grants for emergent black french women artists in partnership with Château de la Haute Borde

Over half a century later, curator Amandine Nana has been picking up this legacy by once again finding space in Paris for Black artists to be seen, felt, and remembered. As an art history student with a background in urban and African studies researching the forgotten histories of cosmopolitan artistic practices in Paris during the 1950s, Nana grew frustrated by the lack of resources in public libraries. After getting tired of having to search out copies of relevant texts for herself, she decided to start collecting texts in the hopes of creating a specialized Black art library. “I was already doing this work when I began thinking about proposing it to a traditional gallery or an art space,” Nana says. Then, in 2020, during COVID and quarantine, with Black Lives Matter happening globally and Justice for Adama on a national level, she decided to act on the lack of Diaspora cultural spaces in France.

The result is Transplantation, a Paris-based fugitive library, gallery, and cultural organization focused on the contributions of Black francophone art practices to an international diasporic scene. The first mobile experiment took place in the summer of 2020 as a residency and reading room/bookshop that culminated in a month-long exhibition, École Paris-BXL, at the heart of the historic Montparnasse district. With resident artists Mariama Conteh, Assia D., and Aminata N’diaye and the wider group show, which included local artists Cédric Kouame, Adam Bilardi, Maria E. André, and Anthony Ngoya. I, Nana explored the gap between neglected diasporic modern art histories in France and an emerging contemporary francophone scene between Paris and Brussels.

“The first experiment of Transplantation was about the context of Montparnasse as a forgotten site of Diaspora practices,” Nana explains. “The second edition was more about us coming back to familiar multicultural areas in Paris, like the first place where I settled with my family after arriving from Cameroon.” Opening in June 2022, this took the form of a six-week cultural space with an exhibition, reading room, and community program focused on Black French women’s contributions to art history as well as notions of transmission and belonging. Alongside her friend Mariama Conteh – former artist in residence, and now art and public associate for Transplantation – Nana developed a platform to highlight six female artists under twenty-five with one being local to the Saint-Blaise neighborhood and the rest from surrounding areas. The title, Sentiments Grandissants, drew on the popular love ballad by the zouk singer Karima to highlight another emergent practice that is currently being overlooked in favor of white or foreign artists in France. This second iteration of Transplantation also provided a mentorship program for the young artists, as well as studio space and accommodation for one week before the academic year began.

What differentiated Sentiments Grandissants from École Paris-BXL was the community engagement, the effort to connect with a neighborhood and people who don’t often seek out art galleries. Working with the local youth center Wangari Maathai, Nana and Conteh organized a series of drawing and photography workshops for residents aged seven to nineteen, drawing upon the diasporic African imaginary. “It was about popular, artistic, and cultural education in those areas that promotes African or Black artists, because a lot of diasporic people live in those neighborhoods. And we don’t have a cultural offering that fits with their identity,” Nana says. “I really wanted to come back to where I come from, the beginning of my immigrant story in France. I never lived in St. Blaise, but I knew about it through friends and I took playwrighting courses there as a teenager there.”

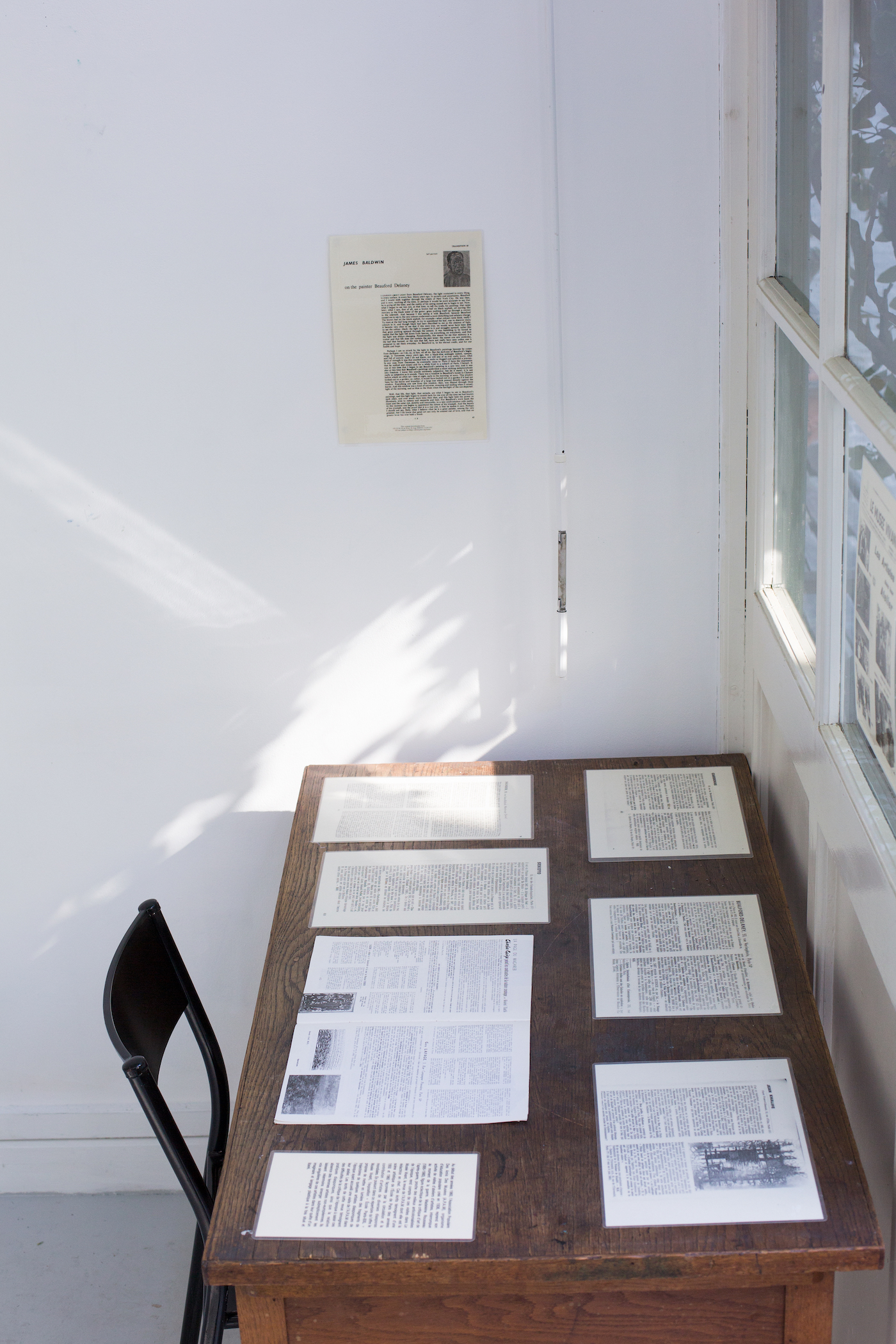

Curated table by Amandine Nana with her archival research on the 1950’s – 1960’s black cosmopolitan art scene in Paris, part of Ecole Paris-BXL, inaugural show of Transplantation in september 2020

When I spoke to her on Zoom it was the end of summer and Nana was about to move to New York for a master’s degree in art history at Columbia University. I could see her surrounded by boxes of books and belongings in the midst of packing up her life for a transatlantic shift. Speaking about her upcoming journey, we began discussing the differences in conversations on race in the United States and France. “I think that France really has an issue with its identity,” she says. “We can think about French-ness in a more nuanced way once we include the history of the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism – if we think beyond white French identities. Globally, I would say that a lot of people know about the Negritude movement, and after 2020’s Black Lives Matter it was quite fascinating for me to see how all those Black French writers like Aimé Césaire and Édouard Glissant were being quoted by young writers and scholars. But in France, we don’t think about them as part of French identity.”

In this next phase of her life and the development of Transplantation, Nana is on the lookout for Black spatial histories that are yet to be explored. She undertakes investigations collaboratively to build the sustainability of these experiments. “I realized that the mobile format is powerful because it allows me to keep exploring contexts like urban Paris, always creating new histories while experimenting progressively on what a diasporic cultural institution can look like. I like the idea of transplanting the thought – to have impact everywhere.”

Yaa Addae is a curator, writer, and artist who works as a community researcher at COMUZI. Their practice is informed by the liberatory power of the imagination,play, and restorative love economics: bringing love to the systemically underloved.

GIVING BACK TO THE CONTINENT

Listen to artist interviews, reviews, features, and opinions about crucial topics on contemporary art, to stay up to date with discussions surrounding art from Africa and the Global Diaspora.

More Editorial