In the “post-war” period, many pioneering Black artists were largely neglected by the Western art world despite their significant contributions, and persevered regardless. In the last ten years Western institutions have been waking up to these artists’ legacies. They are finally curating first retrospectives – and of course the markets have followed suit. In this series we chart their careers, highlighting their artistic evolutions and motivations in relation to the world around them. Here, Liese Van Der Watt writes about Robert Reed’s critically acclaimed abstract paintings, which after a three-decade hiatus are being exhibited again in major shows.

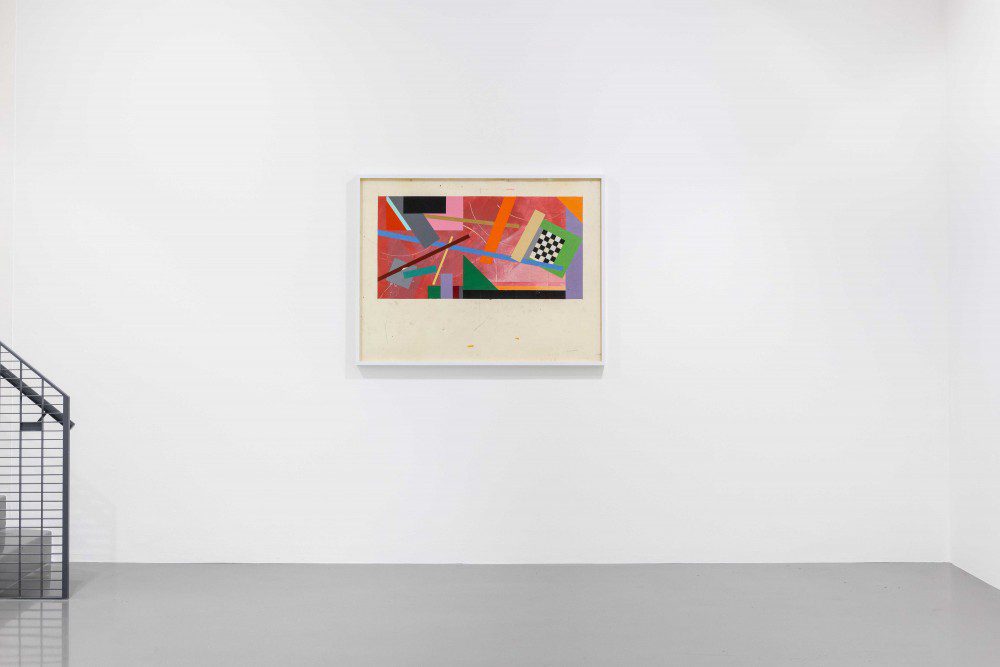

Installation View: Robert Reed: San Romano Series, Pilar Corrias, London. 12 April – 18 May 2019. Courtesy of the Robert Reed Estate and Pilar Corrias, London. Photo: Damian Griffiths.

In 1979 Robert Reed, American painter and adjunct professor of painting at Yale University, visited the National Gallery in London. There he encountered one of three versions of Paolo Uccello’s Renaissance masterpiece of complex perspective, The Battle of San Romano (c. 1438–40). Like many twentieth-century artists – notably Giorgio Morandi, Arshile Gorky, and Reed’s friend Philip Guston – Reed was struck by the density of this painting, impressed by what he described as “the activity, the clash, the pomp and circumstance… the organized confusion.” Reed would spend the next five years responding to Uccello, producing his San Romano series, ten large canvases of complex and colorful abstraction, with references to the physical world skilfully incorporated. When he exhibited some of these works in 1980 at a local gallery in New Haven, the Silvermine Guild of which he was a member, the New York Times described them as being “full of movement and many bright Aqua-Tec colors… good-looking, enormously clever paintings that are dazzling patterns of squares, slats, stripes, checkerboards and arcs, all beautifully balanced against each other.”

Installation View: Robert Reed: San Romano Series, Pilar Corrias, London. 12 April – 18 May 2019. Courtesy of the Robert Reed Estate and Pilar Corrias, London. Photo: Damian Griffiths.

Looking at these very accomplished large-scale works today, on show for the first time outside the US at London’s Pilar Corrias, one is immediately impressed by how contemporary they seem, while harking back to that emblematic US American era of abstraction and post-painterly abstraction. They are monumental in scale, reflecting in abstraction the lances, shields, spears, banners, and flags of the original Uccello. By and large surfaces are smooth with hard-edged areas where remnants of masking tape show, but these are interspersed with more physical brushwork, expressive and painterly, invoking the rich purples of an earlier series entitled Plum Nellie.

Why is it, then, that despite the Whitney acquiring one of Reed’s Plum Nellie works in 1973 (a particularly successful year in which he had three solo exhibitions), despite regular (if small) group and solo exhibitions throughout his career, despite being a student of and consequently an exemplary proponent of Josef Albers’ color theories, despite being an influential teacher to many generations of students at Yale including Stanley Whitney, Rachel Rose, and Tschabalala Self, and despite receiving many grants and awards, Reed is still relatively unknown? True, he was apparently a private person who liked the solitude of his studio in New Haven, but upon his death in 2014 his studio was filled with heaps of canvases, drawings, prints, and lithographs, many of which deserved to be in an institutional context. Why has his name not entered the canon of US abstraction?

Installation View: Robert Reed: San Romano Series, Pilar Corrias, London. 12 April – 18 May 2019. Courtesy of the Robert Reed Estate and Pilar Corrias, London. Photo: Damian Griffiths.

Reed was born in 1938 in Charlottesville, Virginia, and eventually graduated with an MFA from Yale. And although this sentence may appear to describe a seamless journey, it must have been a challenging one for an African American person who went from segregated schooling in the South to the seemingly integrated but still restricted context – socially and racially – of the East coast. Although the little that has been written about Reed does not mention any specific racial incidents, he is framed as an artist “forgotten” by history. The exact reasons for this can only be guessed, but it must be assumed that the US art world of 1960s and 1970s, an era of white male machismo, must have presented its own challenges and exclusions to an African American male. In addition, Reed chose abstraction, and thereby chose not to conform to the expectations – still rife today – that Black artists represent their experience of a racialized world. Staff notes from the 1973 Whitney show reportedly said they “struggled to find terms to describe his practise.” This, after Clement Greenberg’s writings on abstraction and then on post-painterly abstraction were widely feted in the US art world.

Installation View: Robert Reed: San Romano Series, Pilar Corrias, London. 12 April – 18 May 2019. Courtesy of the Robert Reed Estate and Pilar Corrias, London. Photo: Damian Griffiths.

Reed’s works were never completely non-objective though, they always retained their referentiality: they started in the real world with colors and memories of a childhood in Virginia, employing titles that made coded references to autobiographical notes, reproducing patterns from his children’s toys and chessboards, using color combinations of significant schools and colleges, making reference to other painters’ works that he admired. The eventual giant canvases of balanced, colorful, and harmonious abstraction, filled with interesting and surprising references, deserve to be written back into history.

Based in London Liese Van der Watt is a South African art writer and associate editor of C&.

This text was commissioned within the framework of the project “Show me your Shelves”, which is funded by and is part of the yearlong campaign “Wunderbar Together (“Deutschlandjahr USA”/The Year of German-American Friendship) by the German Foreign Office.

INVENTING YOUR OWN GAME

More Editorial