We spoke to the curator of Benin’s first national pavilion – none other than Azu Nwagbogu – about the concept, the artists, and the biennale.

Chloe Quenum, Epopée, 2023. ©Arthur Pequin.

Contemporary And: With co-curators Yassine Lassisi and Franck Houndegla, you are creating a pavilion around restitution and African feminism. How do the two topics come together?

Azu Nwagbogu: They converge and devolve seamlessly into the idea of a “[RE]turn,” with the consciousness of African feminism and the restitution of looted heritage and artefacts. With regards to advocacy around restitution, my curatorial practice has always been about the intelligence around epistemologies around restitution. Of course the shiny objects are important, but I want to focus on the activities we can engage in and learn through before the morality reckoning of restitution is accomplished. A perfect example is exploring Yoruba Gèlèdè traditions. A tradition steeped in the veneration of the mother (nature, mother earth, and female ancestry and knowledge systems), Gèlèdè also attends to the fragility of ecology, the planet, relationships, and all that we hold to be precious in a world where the effects of human activity on the planet are at the fastest and most harmful in history. It’s a challenge and an exploration of Indigeneity as an way to reflect on a viciously capitalist world. If our Indigenous knowledge systems are fragile and precious, how do we strive to restore and preserve them? So for us, restitution is not restricted to objects but includes knowledge systems.

I am grateful for the support of and collaboration with co-curators Franck and Yassine Lassisi, who are from Benin and have been completely invested in the curatorial concept and research.

Ishola Akpo, Erou Kékéré I, 2022. Painting on enamelled dishes. Variable dimensions. Courtesy of the artist and Sabrina Amrani.

C&: Fragility is something beautiful that enables change and transformation, but it can be also very painful, right? Why does the exhibition circle around it?

AN: As you say, in fragility there is also a space for transformation and trust. It is inherently paradoxical for in being fragile there is a strength. It seems to me that being vulnerable is seen as a weakness and hierarchies are built around that perception, but I find strength in vulnerabilities and genuine opportunities to grow and learn. I often think of clay objects that have survived millennia in all cultures – how fragile they are, and how despite that they have survived. The nurturing attention that enabled their survival is the sort of care that the planet, love, relationships, and our humanity need at this time. It is often the most resolute in their shape and form, the rigid and flexible, that snap and break. But the softer and more vulnerable, the memories, the truth, our feelings, empathy, and goodness, endure, return, and are restituted and made whole. You can see that I am an incurable optimist and besides what is the opposite of fragile? If you think about it, it really lacks a definite definition.

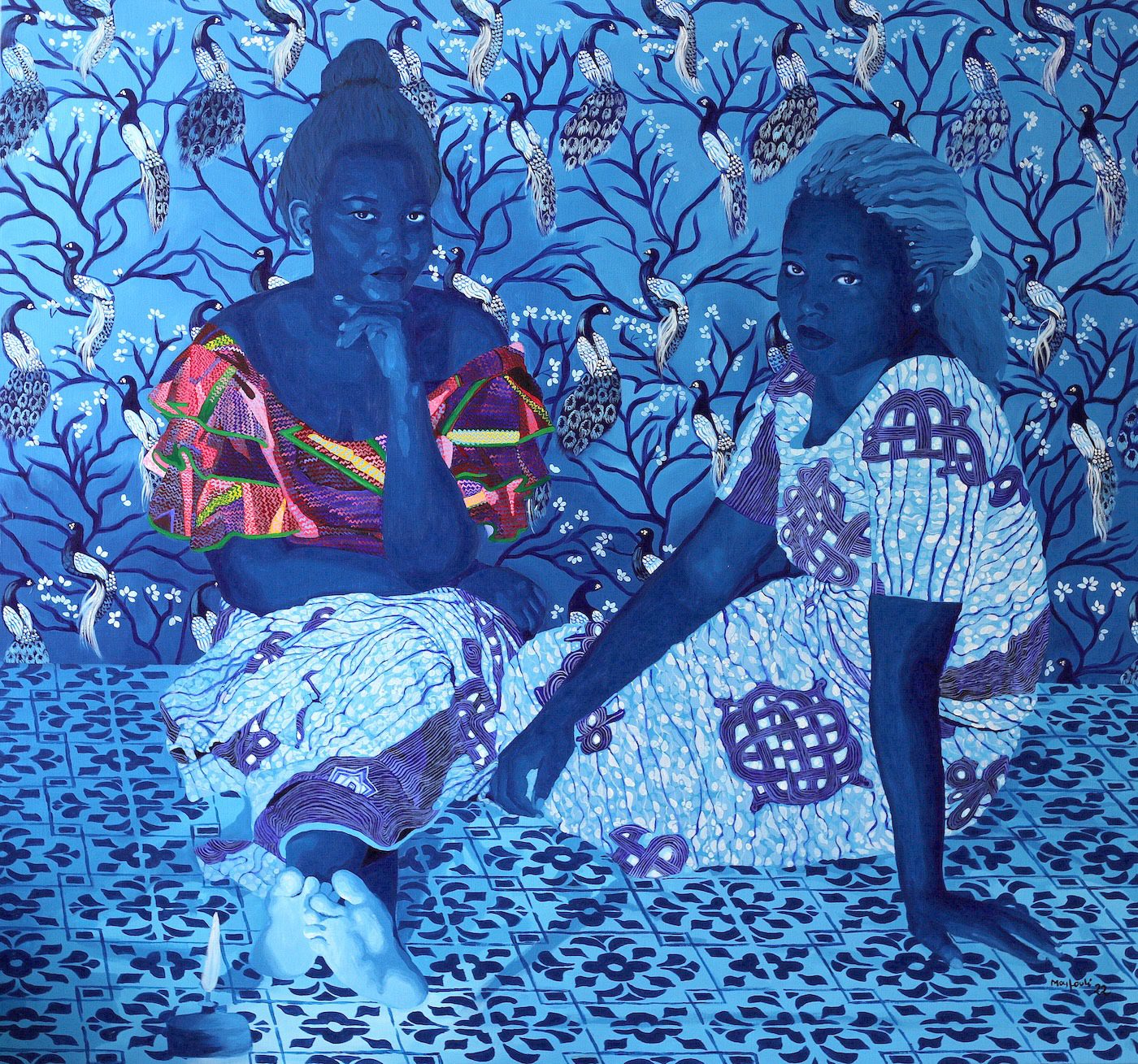

Moufouli Bello, Night Bello, 150 X 160cm. Acrylic on linen, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

C&: I like your selection of artists a lot. Romuald Hazoumé, Chloe Quenum, Ishola Akpo, and Moufouli Bello – they are all working with very different materials and come from different generations and backgrounds. Where do you see their connecting points?

AN: There is a clear intention that means that when you saunter into the pavilion you are encouraged to decelerate your movements such that you really experience the exhibition. The artists weave into each other’s narratives seamlessly and with a leitmotif that keeps the viewer engaged within its central idea.

The connection between all four artists is most certainly based within their understanding of our curatorial concept and the notion of rematriation. They are all concerned by our current ecological, moral, and political world challenges and accept that a shift of focus back to Mother Nature is key to finding solutions going forward. It is always Africa, the ground-zero for humanity and all global events. Here we will find the wisdom for survival through the return of our Indigenous knowledge systems. Hazoumé, Quenum, Akpo, and Bello’s work convene and there is a harmonization between their diverse styles. I often say that it’s a solo exhibition with four artists singing the same tune in different notes.

Romuald Hazoumè, Exit Ball, 2010. 210 cm. Photo Jean Dominique BURTON.

C&: It is the first time that Benin contributes a national pavilion to the Venice Biennale. What do you think this means to the local art scene on the continent?

AN: It is a momentous occasion. The government of Benin truly believes in its artists and the role of artists and intellectuals in shaping society. Having said that, Venice is not our center. But it is a significant launchpad for others to see and understand the history of Benin and the role of contemporary art from Benin. The local art scene should greatly benefit from this and I believe Benin is showing leadership on the continent with its approach to art and culture.

The 60th Venice Biennale will open from 20 April through 24 November, 2024.

Azu Nwagbogu is the founder and director of African Artists’ Foundation (AAF), a non-profit organization based in Lagos, Nigeria. He is also founder and director of the annual LagosPhoto Festival and creator of Art Base Africa, a virtual space for learning about contemporary African art. Nwagbogu was elected interim director/head curator of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art in South Africa from June 2018 to August 2019.

Interview by Theresa Sigmund.

60TH VENICE BIENNALE

C&’s second book "All that it holds. Tout ce qu’elle renferme. Tudo o que ela abarca. Todo lo que ella alberga." is a curated selection of texts representing a plurality of voices on contemporary art from Africa and the global diaspora.

RESTITUTION

More Editorial