Looking at The Intersection of Time

While it feels like through regulations the experience of time is covering, it is still experienced differently. Some have too many, some far too little. It is a question of privilege, of class. How do we interpret and apprehend what we are seeing and experiencing? Are privileged notions of “time” becoming more important than others? …

While it feels like through regulations the experience of time is covering, it is still experienced differently. Some have too many, some far too little. It is a question of privilege, of class. How do we interpret and apprehend what we are seeing and experiencing? Are privileged notions of "time" becoming more important than others? Who can judge whose time is more "prescious" than the other? Who is allowed to judge?

Time to explore the unknown and to reframe what seems incontrovertible. To take a rest at the intersection of time. To get lost.

Jacob Lawrence, And the migrants kept coming, from The Migration Series, 1940–41.

<figcaption> Jacob Lawrence, And the migrants kept coming, from The Migration Series, 1940–41.

Jacob Lawrence portrayed the Great Migration in a 60-panel series, in which over six million African American fled from the rural south, caused by the poor economic conditions and the racial segregation to the industrial North.

“Following the example of the West African storyteller or riot, who spins tales of the past that have meaning for the present and the future, Lawrence tells a story that reminds us of our shared history and at the same time invites us to reflect on the universal theme of struggle in the world today: “To me, migration means movement. There was conflict and struggle. But out of the struggle came a kind of power and even beauty. 'And the migrants kept coming' is a refrain of triumph over adversity. If it rings true for you today, then it must still strike a chord in our American experience.”

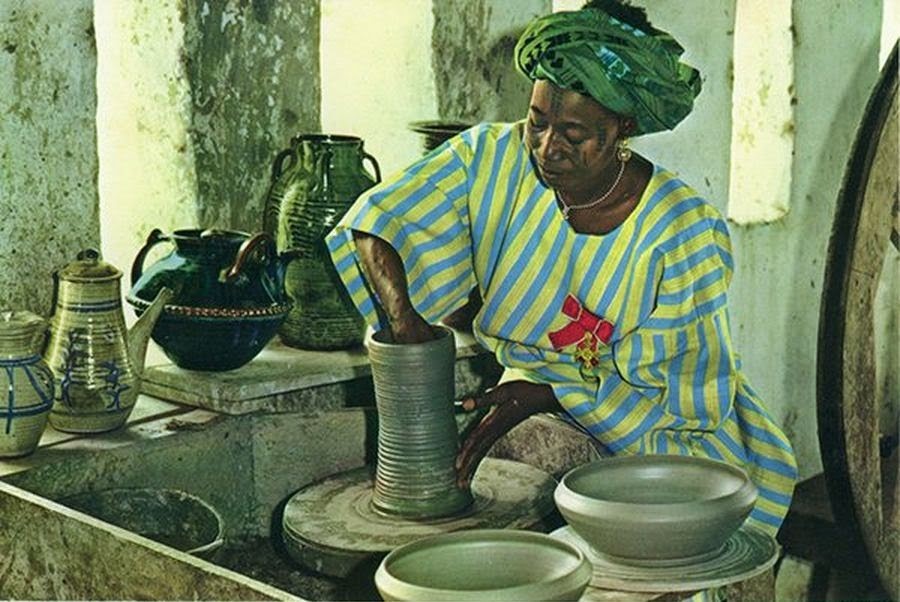

Lady Kwali (1925–1984)

<figcaption> Lady Kwali (1925–1984)

Ladi Kwali became the first woman to be trained in the Abuja Pottery Center in Nigeria and encouraged others to join, till 1965 a new pottery center was established, run by four women.

“Ladi Kwali’s hybrid technique blended the customary Gwari method and symbolic motifs ornamentation, which she learnt from her aunt from when she was nine years old, with Western techniques of wheel throwing and glazing, which she learnt from the Abuja Pottery Training Center, while still using the traditional open firing method with herbal glazes. Ladi Kwali’s artistry changed the face of modern pottery around the world. In acknowledgement of her achievements, Nigeria adorns the Nigerian 20 Naira note with her picture, the only woman to have such honor.”

https://artwa.africa/pioneer-of-modern-pottery-in-nigeria-bio-timeline-of-ladi-kwali/

Felicia Ansah Abban, Untitled, ca. 1960s – 1970s

<figcaption> Felicia Abban, Untitled, ca. 1960s-1970s, Photography, Courtesy Felicia Abban Estate

“It is through this lens, in these moments of (post-)production between fantasy and reality, that I think of Felicia Abban’s studio portraits. In a realm where we can see that stories can be created and future lives can be imagined.”

Billie McTernan on Felicia Ansah Abban

https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/felicia-abban-behind-the-scenes/

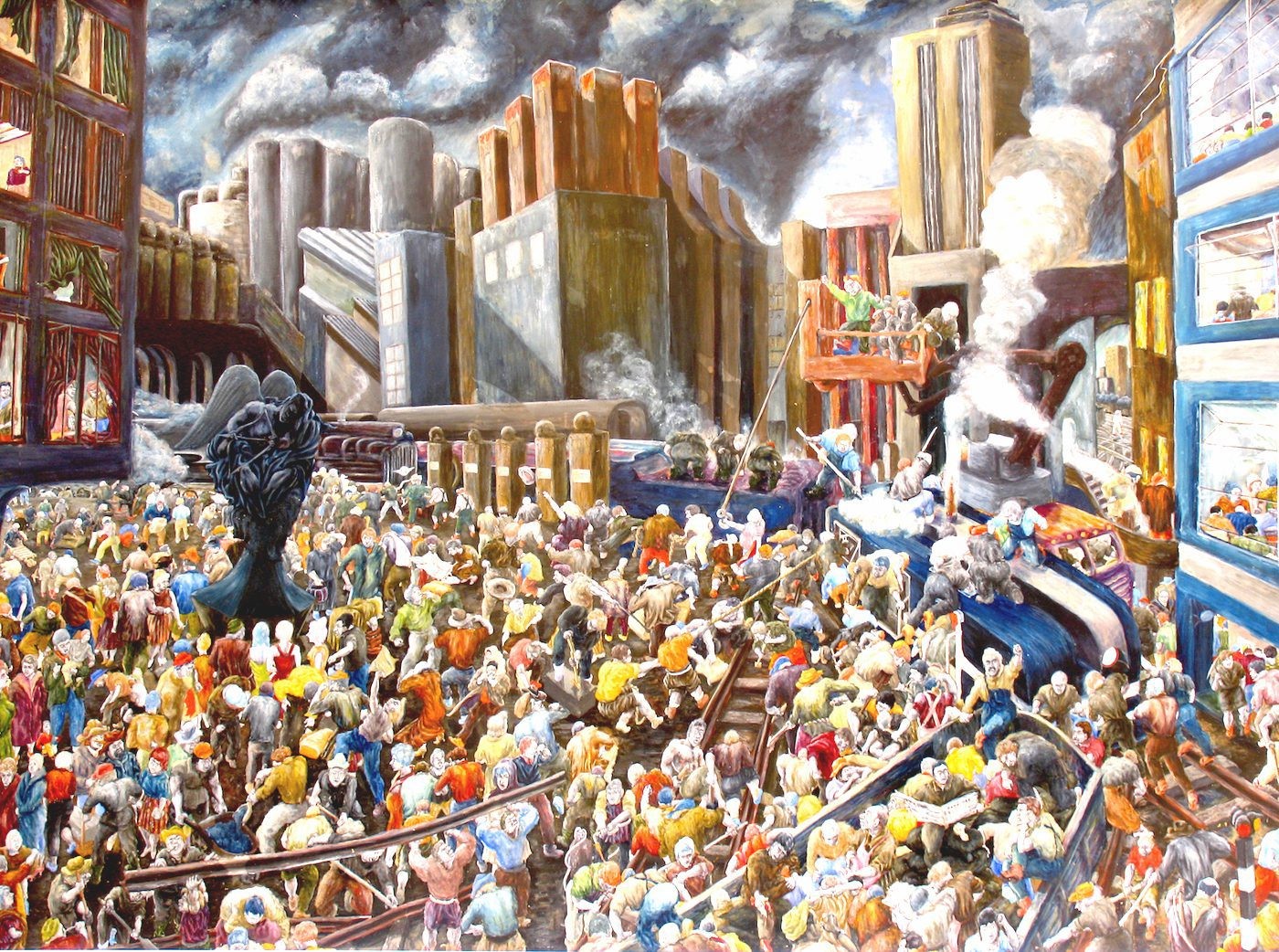

Henry Tayali, Destiny, 1957-1980

<figcaption> Henry Tayali, Destiny, 1975-80, oil on canvas, 58cm x 89cm. Courtesy of Zukas Family

“He created Destiny in his formative years, reflecting the things he used to see around him. Yet his arguments against racial prejudice, injustice, and poverty also found expression in his later works. Tayali responded to contemporary issues that concerned the African liberation, the post-colonial condition, and the welfare of the average person.”

Andrew Mulenga on Henry Tayali

https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/outside-the-spotlight/

Howardena Pindell, Untitled, 1972

<figcaption> Howardena Pindell, Untitled, 1972. Acrylic on canvas, 174.3 x 267.3 cm; 68 5/8 x 105 1/4 inches © Howardena Pindell. Courtesy the artist, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

“Even an informed visitor might not think of the phrase “genius artist” when looking at Pindell’s works in Victoria Miro gallery. Its association with male artists is yet to be broken even in these “woke” times.”

Sabo Kpade on Howardena Pindell

https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/the-consistency-in-howardena-pindells-art-and-defiance/

Charles Nkosi, Soweto at dawn, 1979

<figcaption> Charles Nkosi. Soweto at dawn, 1979. Watercolor and ink; 42 x 44 cm. Fort Hare University De Beers Collection, taken from De Jager, E.J. 1992. Images of Man: Contemporary South African Black Art and artists, University of Fort Hare Press: Alice, pg 184. © Charles Nkosi.

“Like many other Black artists at the time, Nkosi was compelled to make art in response to the conditions of his people. While many of his contemporaries were leaving the country, he chose to stay. This characteristic resonates throughout his work: a patient display of those who stayed.”

Bysame Mdluli on Charles Nkosi

https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/the-black-theology-in-sokhaya-charles-nkosis-paintings/

John Biggers, Mural Christa V. Adair, 1983

We don’t know how long it took John Biggers to create his impressive mural honoring the black civil activist and suffragist Christa V. Adair. But made in 1983, it is a detailed study of African-Amercian history and a critic of racial and economic injustice. Biggers is a pioneer in many ways. He was one of the first known African-American artists to travel to Africa and who incorporated African and African-American influences in his arts to tell stories that haven’t been told before with art.

"He just really was ahead of his time," Wardlaw said. "No one was talking about Africa as a place for knowledge, a place that had secrets about the universe."

Rosemary Karuga, Untitled, 1998

<figcaption> Rosemary Karuga, Untitled, 1998. 40x57cm. Courtesy Red Hill Art Gallery

“Karuga is a significant link between the past and future of women artists in East Africa today. She is also a respected innovator who dared to branch out and break new ground with her art, hence paving new pathways for others. Using the easily accessible material of newspapers and magazines, Karuga has over the years developed an approach to collage that at the time was unique in East Africa. Her images harness both extraordinary detail and charming simplicity.”

Mbuthia Maina on Rosemary Karuga

https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/rosemary-karuga-unearthing-hidden-artistic-treasures/

Akinbode Akinbiyi, Victoria Island, Lagos, 2006

<figcaption> Akinbode Akinbiyi, Victoria Island, Lagos, 2006. From the series Lagos: All Roads. Courtesy the artist

“What matters is being sincere and aware of the inner impulses that course through us all when making images. It is not the environment that determines the approach, but rather how you stand in relation to yourself and what you want to say, to see, to create. My approach to mentoring is to gently urge younger colleagues, to hear their inner voices, see their inner eye, and take it from there. The location of teaching is of little importance.”

Akinbode Akinbiyi in conversation with Rahima Gambo

https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/camerawork-now/

Pascale Marthine Tayou, Branches of life, 2014

<figcaption> Pascale Marthine Tayou, Branches of life 2014, ifa galerie Berlin. Photo © Elsa Guily

“In the end I would like to whisper to you the summary of the history of the ‘colonial ghost,’ shake the tree to free it of some of my evils that lurk day and night in our collective memories, talk about haunting and injustice without making new victims, reveal a few lines of the secrets hidden in my bedside notebook, sing the heart of my choruses without any grudges, deliver you to yourselves… ”

Pascale Marthine Tayou in conversation with Elsa Guily

https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/rejoining-the-times/

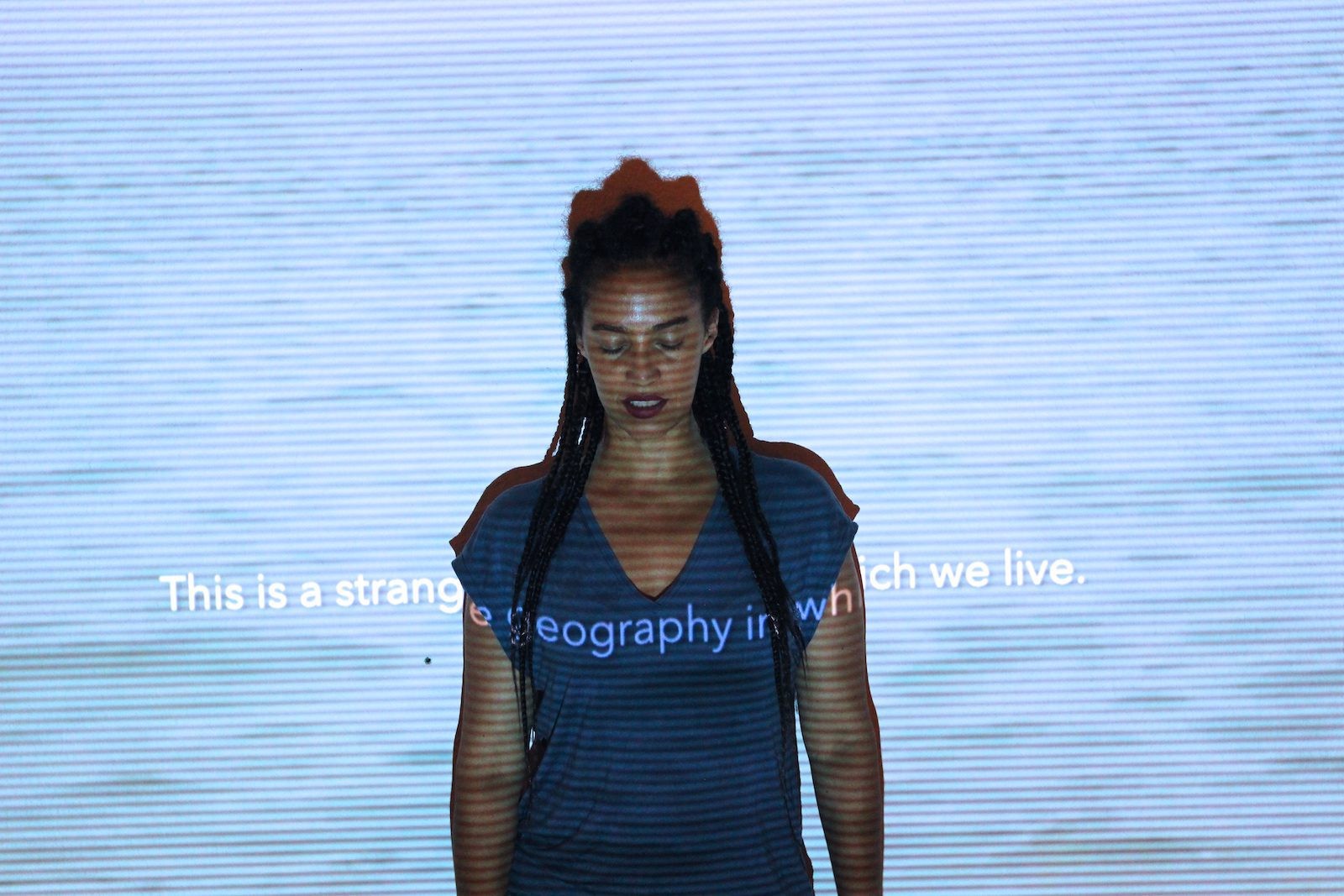

Grada Kilomba, Illusions, 2016

<figcaption> ‘ILLUSIONS’ by Grada Kilomba. Photo by Moses Leo (2016). Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery.

“And with the fact that the theory of memory is actually a theory of forgetting. We remember because we cannot forget. And this is the constant relation between the past, present, and future. As a Black female artist, I often feel like living in a space of timelessness.”

Grada Kilomba in conversation with Theresa Sigmund

https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/living-in-a-space-of-timelessness/

Jota Mombaça, The Feel of a Problem, 2018

<figcaption> Jota Mombaça, The Feel of a Problem, Berlin Biennale 10 #1 Public Program. Photo: Anthea Schaap

“I really think it was because somehow I felt that day that, no matter how, I had decided to fight against the coloniality that I was holding within my body. And even if this struggle cannot be overcome, as it is mostly frustrating, contradictory, complicated, and self-destructive, it is however a struggle that is worth fighting.”

Jota Mombaça in conversation with Will Furtado.

https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/exploring-the-body-as-colonial-occupation/

Alisha B. Wormsley, There are Black People In The Future, 2018

<figcaption> Alisha B. Wormsley, There Are Black People in the Future. Part of Manifest Destiny, curated by Ingrid LaFleur. Image by Alessandra Ferrara, Courtesy of Library Street Collective, Detroit.

„If there are no black people in your vision of the future, it is —most certainly—the past.“ - Eric Otieno on Alisha B. Wormsley’s site specific installation There are Black People In The Future

https://www.sleek-mag.com/article/afrofuturism-kunstlerhaus-bethanien/

Michael Armitage, The Promised Land, 2019

<figcaption> Michael Armitage, The Promised Land, 2019. Courtesy the artist and White Cube Gallery

Michael Armitage makes oil paintings on Lubugu bark cloth. Every painting starts with the process of making the bark cloth, where the bark is peeled off the tree, soaked, burned, beaten so it turns from a hard bark to a soft cloth. Each painting takes several months and sometimes years. The artist wanted a material that from the start would undermine the fact that these are paintings. Because painting on canvas has a very specific story, that is connected to certain cultural questions and associations, he didn’t want to deal with.

https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/michael-armitage-painting-from-afar/

David Alabo, Sablier, 2019

<figcaption> David Alabo, Sablier, 2019. Digital Art Print. Courtesy the artist

“(Afro-Futurism) calls on us to ask what freedom for Black people will look like in the future. Futurism and Surrealism are similar in that they both rely heavily on the speculative—endless possibilities that continue to change, with time as the main influence.”

“Afro-Futurism is more than an aesthetic trend—it’s a beacon of hope and an escape from the harsh realities of the now.”

David Alabo in conversation with Russel Hlongwane

https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/black-mirrors-and-afro-surrealism/

Black Quantum Futurism

[video poster="https://contemporaryand.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Bildschirmfoto-2020-06-05-um-13.29.13.png" width="3256" height="2160" mp4="https://contemporaryand.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Black-Quantum-Futurism_01.mp4"][/video]

“We reappropriate time as a weapon and tool to fight back against temporal oppression.”

Clara Hermann: Can you give examples for the temporal technologies Black women have developed to ensure the quantum future(s)?

Rasheeda Phillips: Any and everything! Our writing, our music, our hairstyles, our art, the way we dress, the way we talk, our rhythms and movements. All the ways in which we modify time and survive through the oppressive linear timeline in a world that actively tries to erase us from the future.

Rasheeda Phillips in conversation with Clara Hermann

https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/black-futurism-technologies-of-joy/

Opinion

The Olympia Effect: Who Gets Credit for Sexual Liberation On/Off Screen?

A Collector’s Guide to São Paulo

Dignity Under Duress: Black Figuration Beyond the Global Art Market

Opinion

The Olympia Effect: Who Gets Credit for Sexual Liberation On/Off Screen?

A Collector’s Guide to São Paulo