The saxophonist and composer from Philadelphia speaks about his new album and how visual art informs his music.

Immanuel Wilkins - The 7th Hand (Blue Note Records)

Contemporary And: While touring with Jason Moran’s The Bandwagon, you became interested in the intersection of music and visual art. What sparked this interest, and how influential was Moran, who produced your debut album Omega (2020), and famously says: “Exhibitions during the day, gigs at night”?

Immanuel Wilkins: In high school I did my senior project on Jan Vermeer and was in love with the works of Rembrandt and Caravaggio. I wrote some music based on a piece by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and at Juilliard I also took art history courses. Jason would always be pretty adamant about me getting out and finding inspiration while on the road, before gigs. He would drag me to exhibitions, which was the kind of energy that I needed to thrive off when playing at night – because we played the same music every night.

I was also fascinated by studying the music of Ornette Coleman and Charlie Parker. I realized that they were very close with other artistic disciplines during their time. It feels like there’s more of a disconnect between music and art nowadays than there was then. For me, it was a conscious effort to find artists that were around my age or older, that I could get around and be inspired by and talk with and work with. I was like, “Man, I gotta kind of bridge that gap, you know?” I think Jason Moran is at the forefront of that.

C&: In your work with filmmaker and multimedia artist Cauleen Smith, the roles are reversed: your music inspired her visual artwork. How did you get to know each other, and how did that collaboration come about?

IW: Cauleen had an exhibition at the Whitney Museum that challenged me, so I reached out. I had some ideas that I had developed via a mood board for myself. I was like, “Look, Cauleen, I have all these ideas, can we synthesize this into some sort of project?”

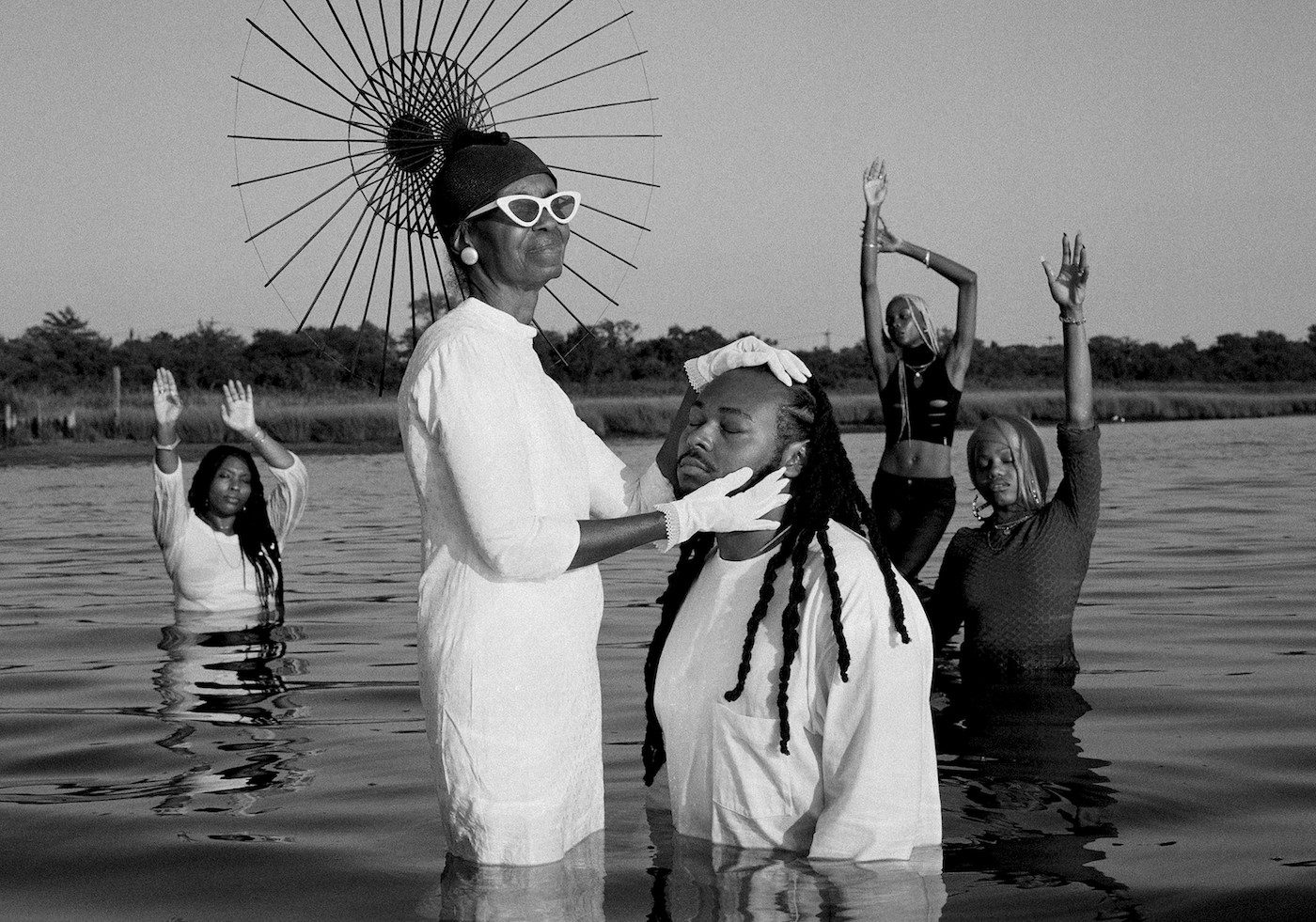

C&: The video [for the two singles “Emanation/Don’t Break”] really captivated me – the aesthetics, the narrative, the interplay of sound and image. The music seems to lead the way, carry the images, and there is a back and forth of images to the rhythm at the end, on point. Were you figuring out the visuals together?

IW: Cauleen was moving between LA and Chicago. I was moving between Philly and New York. So most of the work was remote, a lot of zoom calls, texting back and forth. I remember talking about the idea for the first song, “Emanation,” being about the power of gathering together. What if gathering could essentially produce some sort of emanation, right out from a source?

C&: What does emanation mean to you?

IW: It literally means that something jumps out from a source or originates from a thing, like a solar flare. Arthur Jafa often talks about emanations referring to Fred Moten. It’s something that kind of darts out from something else. There’s a Bible verse that talks about an emanation from the Holy Spirit. It says, when two or three are gathering together, there am I in the midst. That’s basically God saying that he emanates from this gathering. So a part of me was figuring out different visual symbols I could come up with, that felt like emanations.

C&: Could you describe these?

IW: For the first one I was thinking of water as a sacred thing with the idea of baptism in mind, but also as a central symbol of the African Diaspora and the transatlantic slave trade. Water inherently carries a transformative power. It can heal you, or it can kill you. The other element was air, and I examined how it replicates a feeling of a spirit. Air and wind as things that you can’t see, but engage with. Cauleen came up with the idea of fishing and kite-flying as tidal emanations out of water and air, people holding fishing rods or flying the kite. It’s really coded material that has many layers of abstraction, a real generative source of meaning.

C&: At the end of the film, the protagonists come in and out of the ropes of Double Dutch, two threads that form a bubble because of the fast swinging.

IW: Cauleen mentioned the idea of these women studying, reading books, being on this path to liberation. It was an overarching concept for the whole album, thinking of safe spaces. Double Dutch is a safe space on the street. It’s being played in the neighborhood, in somebody’s corner, a similar experience to that in hair salons. The gathering there feels safe.

C&: Was the album completely finished when you started working with Cauleen?

IW: The mood board was ready, before we even went to the studio. So I had an idea of the visual aesthetic as part of the meaning behind the music before we got in. In a way I was referencing the material before we had it. When I first wrote “Don’t Break,” which is based on Double Dutch, I remember my drummer told me, “Man, this song is like a dance, and you can’t break the dance.” That’s where the title came from. We simply can’t break the formation. I started thinking about all sorts of Black footwork and the correlation to shouting in church. I asked him to record some African drums, thinking about their role within diasporic spiritual practices. They are used to call down a deity, and whoever is dancing to the drums gets possessed by them. That happens in West African drumming, but also in Black churches – with shouting, and expressing the relationship between the shout, the beat, and the actual dance. I thought that was an interesting thing to correlate. So the theme became spirit possessions as central to the drums and the dance.

I took it a step further with line dancing, Double Dutch, or any sort of Black dance or Black footwork that was on my mind. Because like the stream of consciousness, improvisation happens in the confines of two ropes around.

C&: The music indeed goes on and on, never breaks, and the dancers try to stick to that rhythm with their footwork. It feels like a jazz improvisation.

IW: It is like a continuous trying, a continuous reworking of the same thing. That was another kind of narrative arc from Cauleen Smith. She was thinking of the process of Double Dutch as one of trying until at the end, so the dance basically keeps merging into something where the band drops out and it’s just drums.

C&: Was it clear to you how strong the images would influence the way your music is consumed afterwards?

IW: I think images are just as powerful as sound, people have a sonic memory just as they have a visual one. The video affects how people listen and consume. I want to be conscious about how I present my music and make sure it’s internalized in a way that makes the music speak.

Paola Malavassi (*1978, San José, Costa Rica) is a Berlin-based curator and author. Her research interests include music and dance with a focus on African American music and culture. Malavassi’s interdisciplinary approach became evident in her recent curatorial work such as “Stan Douglas: Splicing Block” (2019) and “APEX VARIATIONS” (2018) by the artist Arthur Jafa and the jazz pianist Jason Moran. She is founding Director of DAS MINSK Kunsthaus in Potsdam.

OVER THE RADAR

CONSCIOUS CODES

More Editorial