Dignity Under Duress: Black Figuration Beyond the Global Art Market

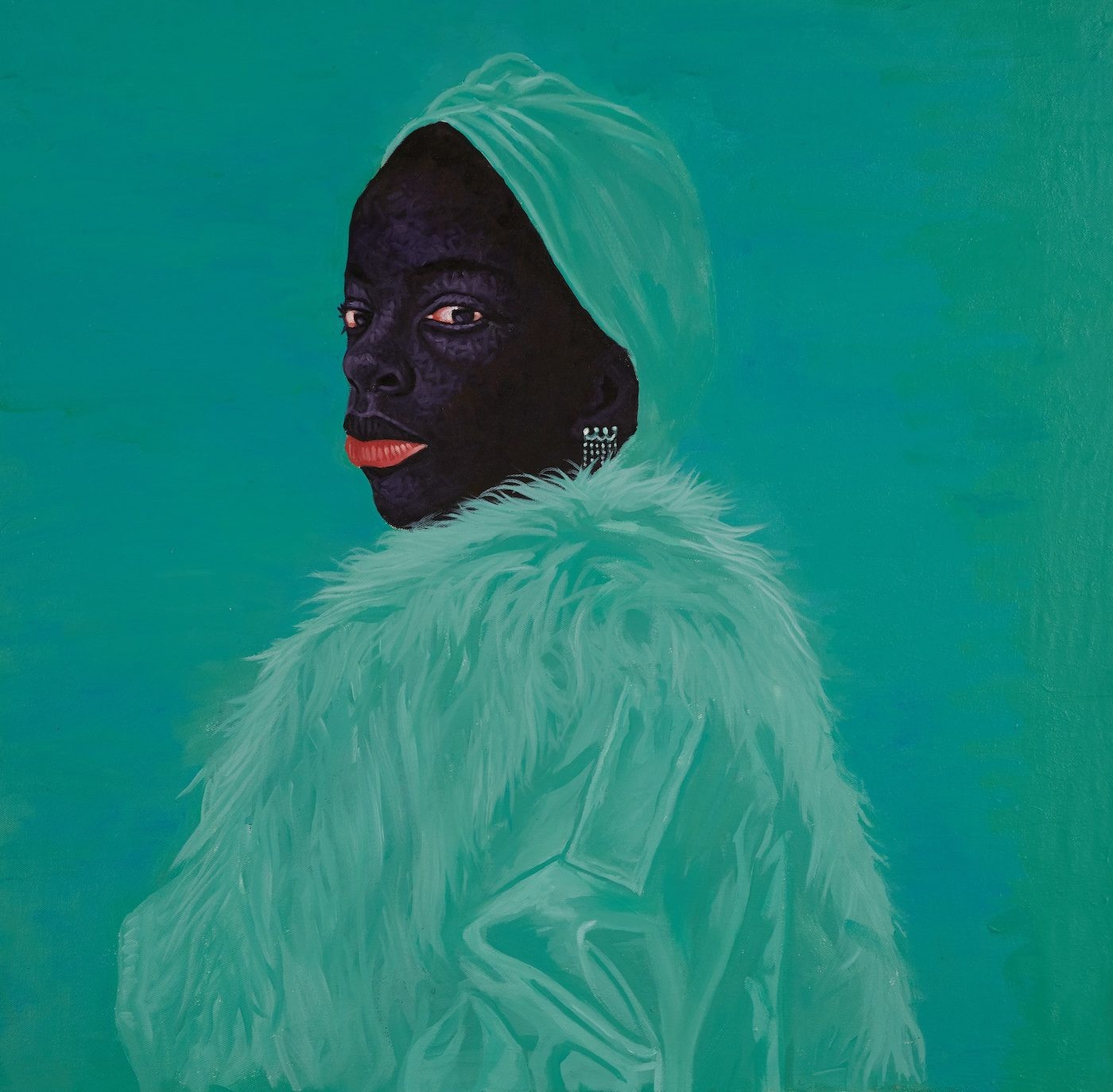

Kwesi Botchway, Green Fluffy Coat, 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 78.7 x 78.7 cm / 31 x 31 in. Courtesy of Gallery 1957.

The global market embraced art from Africa—but is that alone enough to sustain it? Writer Elikem Logan calls for a shift away from reliance on the altruism of Western institutions and towards an art industry beyond markets.

In March 2025, Wienerroither & Kohlbacher gallery unveiled a dazzling painting by Gustav Klimt at the TEFAF art fair, both in Maastricht and later in New York. The picture depicts William Nii Nortey Dowuona, a chief from the Ga ethnic group in the south of modern-day Ghana, who had been brought to Vienna in 1897 as an exhibit for a ‘human zoo’. Rendered in Klimt’s loose painterly style, the subject is draped in the ceremonial cloth still worn by Ga people today. The portrait radiates a quiet yet resilient dignity, despite the dehumanizing circumstances of Dowuona’s presence in Austria.

This reduction of the status of a ruler to an ethnographic exhibit reveals the paradox of colonial visibility. The colonial subject’s presence in global discourse is often possible only by passing through the interpretive framework of the colonizer – a framework that simultaneously enables recognition and constrains meaning. A sense of Nii Nortey Dowuona’s gravitas endures in this painting, but only through Klimt’s gaze, which transforms him into both subject and object, an artefact crafted to satisfy European curiosity. His dignity is circumscribed by a narrative that negates his autonomy.

The portrait’s quiet contradiction – dignity under duress – reflects the ongoing challenge for art from Africa: to be seen on the world stage, it seems that it must be shaped and often distorted by external systems of validation.

One example of this contradictory phenomenon is the defeatist narrative associated with Africa’s participation in the global art market. I was recently sent an article published by US magazine Vulture entitled “How the Black Portraiture Boom Went Bust.” Based on a small sample of Ghanaian artists, including Kwesi Botchway and Serge Attukwei Clottey, the article frames the market ascent of Black figurative art as a byproduct of racial reckoning following the 2020 killing of George Floyd. Supposedly, buyers keen to purge their white guilt flooded into the market for so-called Black art, only to flee in 2023 after a global market downturn.

On a basic level, the numbers tell a similar story. According to London-based market analysts ArtTactic, auction sales for modern and contemporary art from Africa fell 8% in 2023 to US $79.8m, then dropped another 45% to $43.9m in 2024. But beneath the top line, the reality is complex. Sales of twentieth-century African artists remain strong. Fairs dedicated to art from Africa, like the multi-location 1-54 and the Investec Cape Town Art Fair, post healthy results. In South Africa, Strauss & Co. has seen a rise in sales. In line with the wider trends in the global market, the overall volume of artworks sold in 2024 increased by 13%, even as the total value of those works fell.

There is a case for seeing buyers of art from Africa as motivated simply by guilt or financial gain rather than passion. Botchway himself alludes to this in the Vulture article: “There were collectors who didn’t even want to understand what the artist was talking about.” But this view overlooks the largely African collector base who continue to support the growing market. What we are witnessing is not the death of a movement but a shift in buyer attention away from ultra-contemporary hype – perhaps toward undervalued artists with deeper art-historical significance. There was some speculation in the market, but to describe Black figurative art as the brief beneficiary of a BLM-fueled trend is as lazy as it is limiting.

In fact, the rise of Black figurative art was and remains a landmark moment, one that gave global visibility to a generation of African and Diasporic artists on their own terms. It is much easier to label the phenomenon a trend than to consider why it was embraced, what it represents, and what its ongoing metamorphosis will produce. The forces that define an art-historical movement – artistic innovation, institutional growth, and cultural resonance – rarely make it into market reports.

The real issue here is not the fickleness of art markets, but Africa’s dependence on external gatekeepers to make sense of itself. There can be no doubt that Black art should receive critical engagement outside Africa, but African institutions must have the capacity to substantively shape narratives which sustain global acclaim for artists in Africa and the Diaspora. When Western galleries, collectors, and media hold the power to unilaterally anoint and abandon artists, those artists’ legacies become vulnerable to the whims of Western taste, fashions, and tokenism.

What is needed now is not retreat but recalibration. The path forward lies in building locally grounded, globally engaged, self-sustaining systems of validation. That means strengthening ties between artists, curators, critics, collectors, and institutions across the continent. It means investing in archives, exhibitions, publications, and education. It means forming a critical vocabulary that emerges from African contexts, not just in response to external attention.

Just as our Ga chief’s dignity depended on Klimt’s merciful gaze, Africa’s cultural self-image still leans on the altruism of Western institutions. The alleged smuggling of that very portrait sharpens the moral contradictions of Black figuration’s circulation — where works born of exploitation are laundered into masterpieces, their origins obscured as their value rises. This is the cycle that Koyo Kouoh’s historic 2022 show at Zeitz MOCAA, When we see us sought to break, reframing Black figuration as a century-long act of self-definition rather than a market-driven trend. Kouoh reminds us that the future lies not in visibility alone, but in power – African systems of authorship, accountability, and control. To build that future, we must finish what giants like Bisi Silva, Okwui Enwezor, and Koyo Kouoh have begun: a project of cultural self-determination.

About the author

Elikem Logan

Elikem Logan is an independent specialist and art historian primarily concerned with African modern and contemporary art.

Opinion

The Olympia Effect: Who Gets Credit for Sexual Liberation On/Off Screen?

A Collector’s Guide to São Paulo

An Exhibition Aims at Accessibility Against a Backdrop of Protest in Kenya’s Capital

Opinion

The Olympia Effect: Who Gets Credit for Sexual Liberation On/Off Screen?

A Collector’s Guide to São Paulo