Baloji and the Art of Averting the Evil Eye

Musician, filmmaker, and multitalented artist Baloji talks to C& about his first feature film and how the diasporic relationship gives access to an imaginary world that breaks free from shackles.

Serine ahefa Mekoun: Augure paints intergenerational portraits of four characters considered to be witches, battling against the prejudices and identity assignments that weigh on their destiny. What is the origin of this other mode of storytelling, which is reflected in your work by an invitation to dive into a multitude of universes all at once?

Baloji: I don’t come from a school where the method of telling stories was imposed on me, based on the movie classics that are presented, supposedly, as the only way of doing things. I opted for disruptive codes that do not necessarily correspond to a type of cinema instituted fifty years ago in accordance with a classical narrative approach. There are other ways of saying things that don’t go, for example, via a paean to slowness. We tend to forget the existence of Tiktok and the like—a scene can last for four seconds and you understand immediately what the character wants to say.

It all happened layer by layer, a little at a time, based on empirical experience, learning by myself. My career started out with music, then I did some graffiti and tagging, and after that I got into graphic design, by way of calligraphy, which led me to work with materials for making prints. That enabled me to understand a number of different art forms and as a result I ended up making the costumes for the film.

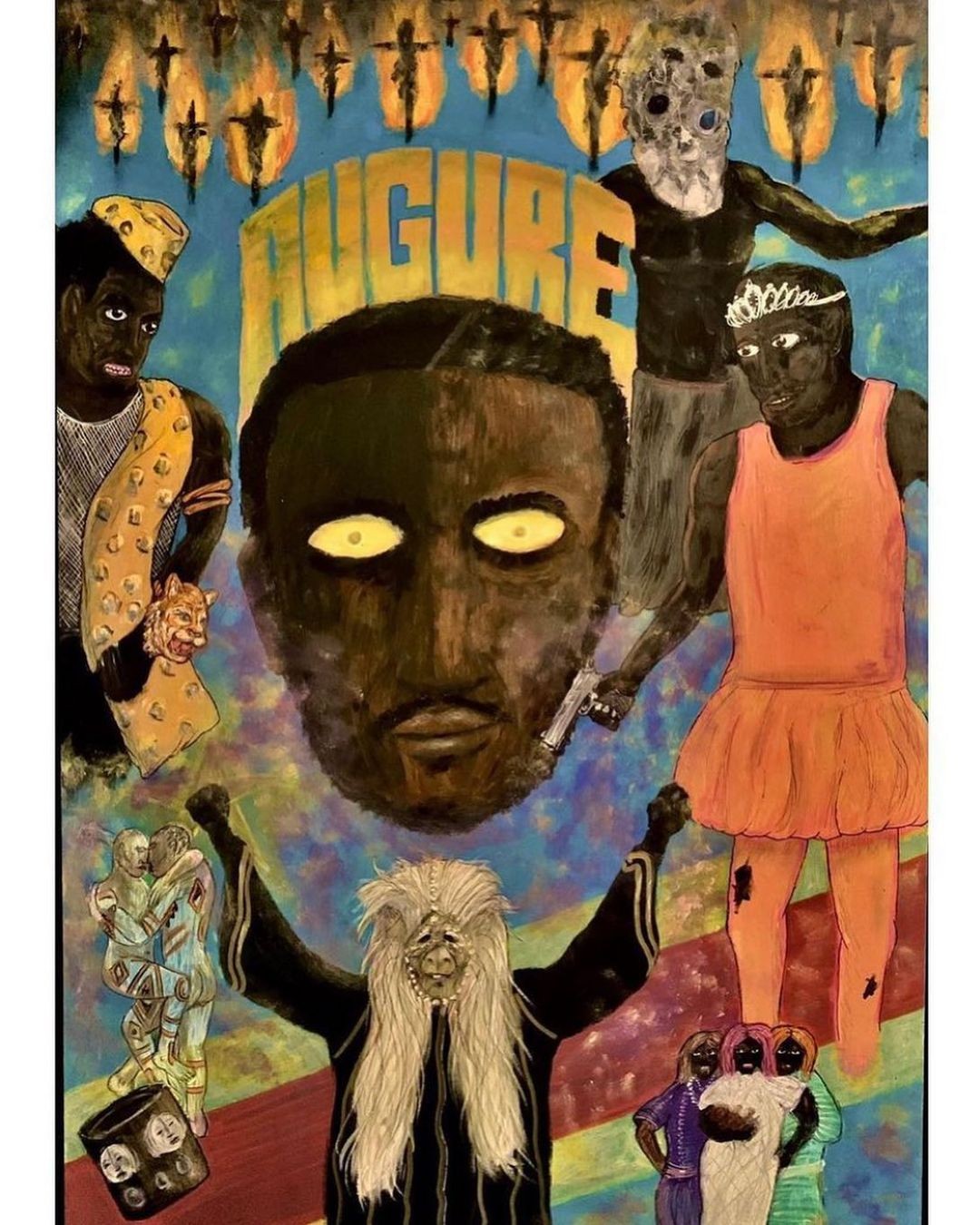

Baloji, Augure, Film Still, Production Wrong Men, 2023.

SaM: How does this tie in with the magical realism that you often refer to when you’re talking about your film?

B: In the film, we see, for example, a mother suffering from post-partum depression. If you don’t want your child, your body reacts. I start with the idea that her milk is purple in order to show how much everything is psychosomatic. Magical realism is a term that gets people to accept a cinematic language that is relatively uncommon outside of South America and Baroque Italian films. Over the last thirty years, I think we’ve spent a good deal of time watching hyperrealistic films in Belgium, and African cinema has remained very classical.

Aside from that, the whole point of the film is the interior/exterior aspect of the diasporic relationship. The gap between inside and outside allows you to create your own reality, since you’re managing a bit of both. And that’s most likely why I talk a lot about magical realism, which is the ability to access this space.

SaM: The film is set against the backdrop of the extractivist universe of mining in DR Congo, which has shaped people’s psyches and bodies at a fundamental level. Can you say more about this choice of setting?

B: I’m not out to suggest naturalism or realism or adopt an approach approximating a documentary idea. Of course, I grew up over there and I know people, but the film’s geography is dreamed up, as an amalgamation of Kinshasa and Lubumbashi, which are a long way apart geographically and politically. A sense of distance has been created between the Katangese and the capital Kinshasa. I grew up with this sensibility, which translates at the political level into the idea of isolating Katanga and, for example, refusing to share the language. I wanted to make it a single country, which is itself a role. The encounter between certain characters generates an awareness of how important mining is for the functioning of society and from a global standpoint: this connection reiterates the place that the work of Congolese miners has in keeping the world running—the extremely small within the extremely large.

Set still by Sackitey Tesa Mate-Kodjo

SaM: Black magic and bereavement are central themes in the film. What is usually viewed by society as sorcery turns out to be a chance for transformation in the face of death. Where does this vision come from?

B: Yes, the film seeks to be a space where grief can be transformed, in which we pay constant homage to those who have departed. It also sets itself up in opposition to the all-too-common idea that bereavement lasts a week, when it is actually a process that can last for years. It can disappear and come back at a moment you don’t expect it and carry you away. For example, one of the young characters, Paco, who is perceived as a sorcerer, has actually recreated an entire symbolic universe, permanently honouring his dead sister (involving a dress, a casket, and a pink crown—Ed.). The driving force behind my work—regardless of what form it takes—is poetry. For me, poetry remains "the politeness of despair". It means working on themes that would be too difficult for me to cope with if I approached them in a realistic fashion because that would be too clumsy. It's a way for me to defend myself.

Painting by Nelis Naessens

SaM: À propos of defending yourself, you’ve been talking on social media about all the struggles, obstacles, and structural classism you’ve had to face up to in order to bring this hybrid film into existence, a work that builds bridges between a diasporic experience and the African continent. Can you explain?

B: I've been confronted with lots of rules or people telling me that’s not the way to do it or, worse, making me feel like I didn’t have the skills to do it. Cinema is an artistic discipline with a kind of self-generated elitism. That’s why the word “classism” really touches on the key issue of racism—namely, making a distinction between a person’s level of education and the knowledge they have, which is violent. People would have you believe that there’s only one blueprint, only one way of financing a film or making art in general. As all our funding comes either from Europe or abroad, we are invariably obliged to tell stories that suit the people providing the finance. Luckily, as a musician, I managed to get out of the Belgian straitjacket at an early stage in my career. Once I realized that there’s a way of doing sixty shows a year in Africa without passing through Belgium, it was extraordinary. All this indicates that it’s possible to live as an artist on the continent, without needing to be validated by the West. But it takes a huge amount of effort to step outside of all that, because you’re always being brought back to that state.

Born in Lubumbashi (Democratic Republic of Congo) and based in Belgium, Baloji is an award-winning musician, a filmmaker, and a polymath artist. He works as an artistic director and costume designer for fashion and other forms of visual art. His film Augure has been shortlisted as the Belgian entry for the 2024 Oscar for Best Foreign Film.

Serine ahefa Mekoun is a multimedia journalist, writer, and producer working between Brussels and West Africa. She is interested in all the spaces where different futures can germinate and writes about creative communities and how they activate social change in postcolonial contexts.

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas