What did you think of your year?

22 December 2016

Magazine C&

7 min read

. In July, Stevenson launched its winter exhibition, The Quiet Violence of Dreams, a multi-venue showcase of work by Lyle Ashton Harris, Turiya Magadlela, Zanele Muholi, Mmakgabo, Helen Sebidi and 15 other artists. The show’s name was derived from author K. Sello Duiker’s second novel. Published in 2001, the novel is set in Cape …

.

In July, Stevenson launched its winter exhibition, The Quiet Violence of Dreams, a multi-venue showcase of work by Lyle Ashton Harris,Turiya Magadlela,Zanele Muholi, Mmakgabo,Helen Sebidi and 15 other artists. The show’s name was derived from author K. Sello Duiker’s second novel. Published in 2001, the novel is set in Cape Town and explores what it means to be a new South African unencumbered by what Duiker, in a 2001 interview, described as “the shackles of oppression”. The novel’s chief protagonist is Tshepo, a gay man whose growing awareness of his sexuality engage him in what Duiker in his interview described as “a bigger journey about what it means to be Black, educated”. That journey is ongoing, especially for young South Africans, who in 2016 were involved in lowering university fees, decolonising the curriculum, and freeing their hair.

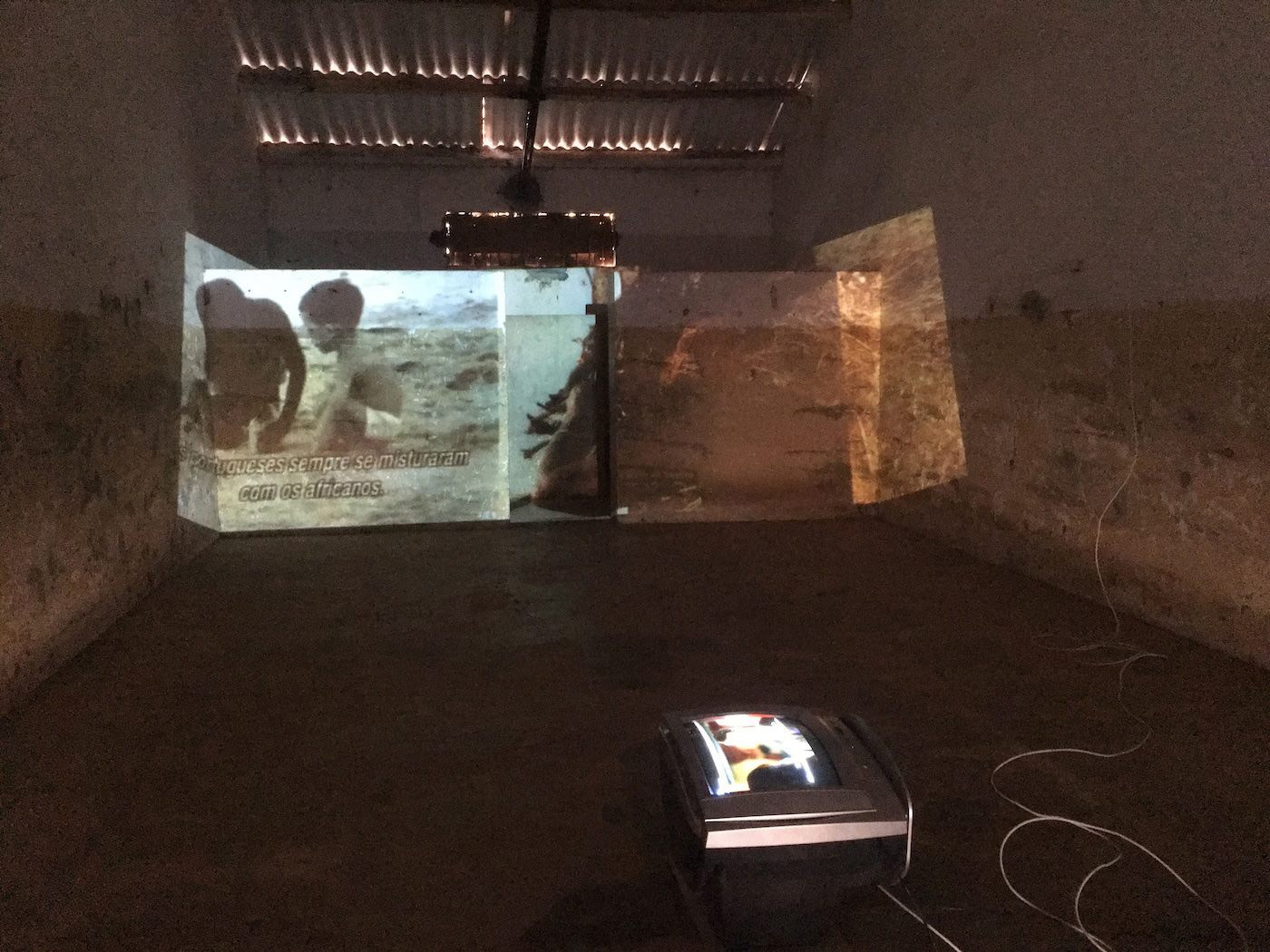

The outstanding artist onThe Quiet Violence of Dreams, curated by Stevenson’s Joost Bosland “in conversation” withMoshekwa Langa, wasUnathi Sigenu. In 2006, Sigenu, together with Kemang wa Lehulere, cofounded Gugulective, a brief-lived artist collective that gave momentum to a new wave of Black artists, writers and curators who, to repurpose something Duiker said in 2001, were “no longer willing to make love to [their] chains”. Duiker and Sigenu, along with writer Phaswane Mpe, musician Moses Taiwa Molelekwa and photographerThabiso Sekgala, are among a generation of post-apartheid artists who died far too young, sometimes of their own volition. Duiker committed suicide in 2005; Sigenu, a Buddhist, died under mysterious circumstances in 2013.

.

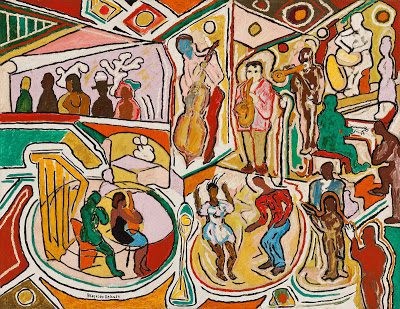

<figcaption> Untitled (Jazz Club), (c.1950). Oil on canvas signed lower left: Beaufort Delaney. Image courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

© Estate of Beaufort Delaney by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator

.

Sigenu was a sustained presence on the Stevenson show, with 24 untitled drawings from 2012 portraying running figures interspersed across the show’s three venues, including Stevenson’s Cape Town neighbour,Blank Projects. Additionally, Bosland also devoted an entire room to Sigenu’s work in Stevenson’s Cape Town HQ, showing four charcoal and pastel drawings and a grainy colour video describing a street performance at a marketplace. In making sense of Sigenu’s work, I resorted to Instagram, posting a detail of an untitled 2011 drawing. I used the word “extraordinary” to describe his deconstructed portrayal of a reclining female nude with four identikit-like studies of anonymously rendered male faces lined-up above the prone body. The drawing is an attempt to render visible conditions of pain, anonymity, entrapment, and eroticism, but is not reducible to any of these speculations.

.

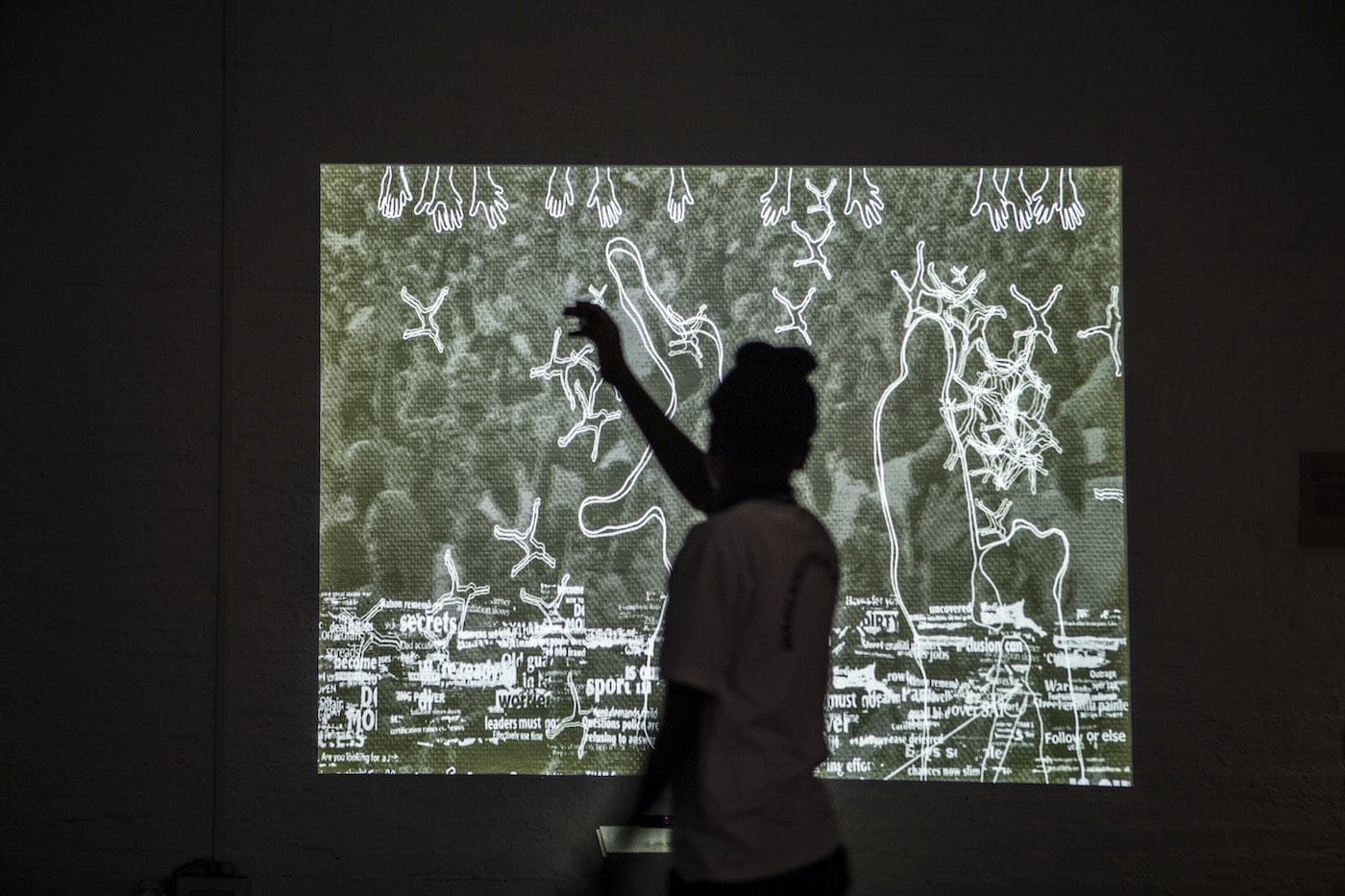

<figcaption> 9. Berlin Biennale für zeitgenössische Kunst / 9th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art 4.6.–18.9.2016 Alexandra Pirici Installationsansicht / Installation view Signals, 2016

.

Why do I mention Instagram? Well, this isn’t a review, merely a digression around a theme: 2016. What did you think of your year? You could, I suppose, answer that question by scrolling through the images on your Instagram account, or revisiting your timeline on Facebook. It is one way to access the highs, lows and in-betweens of a year – your year, my year, that interesting friend of a friend’s year too. We’re all note takers nowadays. In his wonderful 2011 essay “Fieldwork Notebooks,” anthropologist Michael Taussig tries to pin down the elusive quality of keeping diaries and taking notes. The moment an observation is processed, the moment it is written into being, offers Taussig, it disappears. “What disappears is a quality more than a fact.”

Recollection, speculates Taussig, drawing on something Freud once wrote, happens in the “interstices of notation” – in other words, recollection lingers between the claims and statements of the written. But what happens if you don’t make notes? Up until now, I had not written in any concerted way about The Quiet Violence of Dreams, only made brief notes. Speaking at a public event related to the exhibition held at Cape Town’s Book Lounge, I copied down critic Ashraf Jamal’s statement about “the fantasy of freedom, and then the fuck up of freedom”. I also listed the words used by Quiet Violence participating artists Jody Brand and Bronwyn Katz, who sat upfront with Jamal: “sexuality”, “brown body”, “fem”, “intersectionality”, “binary”, “queer body” and – a recurring word – “demonic”.

.

<figcaption> The Quiet Violence of Dreams, 2016. Installation view of Unathi Sigenu's The Beautiful Darkness, Stevenson, Cape Town. Courtesy of Stevenson

.

I heard many of these words used in 2016, notably at theBlack Portraiture[s] III conference in Johannesburg and in the various placards and statements on display at Cape Town’s premier art school, Michaelis, during its shutdown. Queerness, the thing Duiker’s novel foregrounds, also features in the biography of the exiled African-American painter Beauford Delaney (1901-79), whose work was the subject of a remarkable solo exhibition at dealer Michael Rosenfeld’s booth at the Art Dealers Association of America’s fair in the Park Avenue Armory. Should I have rather said I liked Ibrahim El-Salahi’s solo booth in The Armory Show’s Focus: African Perspectives? The line between promotion and criticality is an important one, albeit increasingly fuzzy as old media – along with its entrenched system of ethics – atrophies.

.

<figcaption> Ibrahim El-Salahi, Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams III, 2015, Pen and ink, 154 x 122 cm / 60 5/8 x 48 in. Image courtesy Vigo Gallery

.

In writing about art from South Africa for platforms such as this with addresses in the Global North, I am often asked to write in both modes, promotional and critical. Given my role as correspondent, I’m okay with that. But it can sometimes lead to a distorting sense that the salt borders of the African continent somehow contain the totality of my – and indeed your – experiences of the world. Duiker made this a point of deliberation in his 2001 interview. Speaking of Mmabatho, Tshepo’s worldly female friend, he remarked how she is “her own tapestry, having chosen things she likes about her culture and weaving them with other things that she admires about other cultures”. I like to think of myself this way too.

On my travels through other cultures in 2016, I liked: Dutch sculptor Femmy Otten’s painted sculptures on her show Days Undressed, at Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam; Alexandra Pirici’s choreographed performance cycle in the dark, Signals, included on the Berlin Biennale; and ceramicist Edmund de Waal’s Irrkunst at Galerie Max Hetzler, also in Berlin. I tried to photograph some of De Waal’s delicate black vessels, and failed. “Don’t take photographs, draw; photography interferes with seeing, drawing etches in the mind,” Taussig quotes Le Corbusier in his essay. I should draw more, but as anyone who follows me on Instagram knows, I make notes photographically. Each image is a virtual Post-it note, a reminder that I should as much as want to write about Jared Ginsburg, Banele Khoza and Pinky Mayeng, all names to watch in 2017.

.

Sean O’Toole is a writer and co-editor ofCityScapes, a critical journal for urban enquiry. He lives in Cape Town, South Africa.

Read more from

Identity

Flowing Affections: Laryssa Machada’s Sensitive Geographies

Kombo Chapfika and Uzoma Orji: What Else Can Technology Be?

Cabo Verde’s Layered Temporalities Emerge in the Work of César Schofield Cardoso

Read more from

Unathi Sigenu