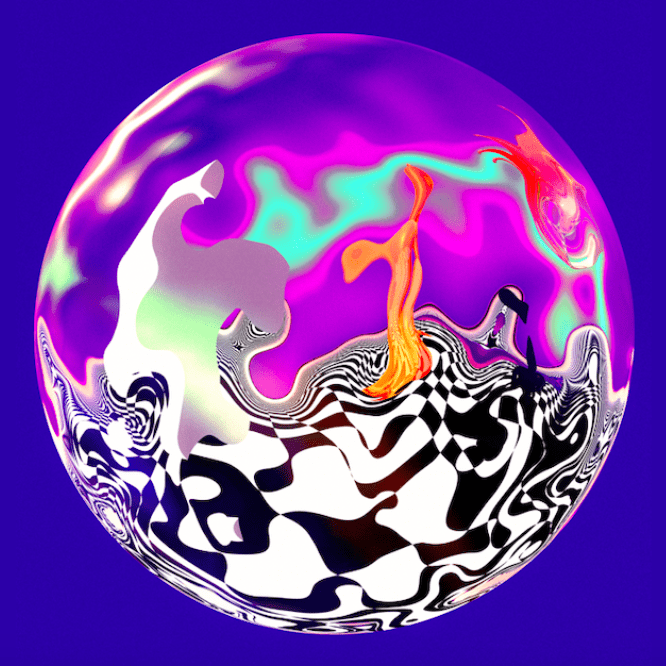

At the beginning of Sam Gilliam’s most famous series of work stands a coincidence. It happened in 1968 in the artist’s studio during preparations for an upcoming exhibition. Gilliam was fixing an unframed painting to the wall when one of the mountings came loose and part of the large canvas landed on the floor. The Drape Paintings series was born, and a new, sculptural moment in painting dawned. The series is characterized by its detachment from the classical frame, transforming the works into spatial experiences. Their installation-like character expanded the formal framework of the medium and propelled non-figurative art. It was arguably a significant, even radical development for post-1945 American abstract painting.

Sam Gilliam, 10/27/69, 1969, acrylic on canvas, installation dimensions variable, approximate installation dimensions: 140 x 185 x 16 inches, (355.6 x 469.9 x 40.6 cm), Collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, photography by Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

Gilliam was born in Tupelo, Mississippi in 1933 and has lived in Washington, D.C. since 1962. At the age of nine he moved to Louisville, Kentucky, where he completed his MFA and began experimenting with watercolors on paper while studying. Even then, his relationship with color and painting was defined by a deliberate loss of control that still persists. « You go with the flow, and you don’t have to play just for the accidental aspect. […] The real thing is not to have control of what happens, just to set it into motion,” he told Hans-Ulrich Obrist in a conversation in 2019.

So it is not surprising that the effect of the Drape Paintings is dynamic and lively. Their hanging is variable; where they are exhibited they adapt to their surroundings, which includes the space in their orbit.

It is often said that Gilliam’s painting style is inspired by jazz, since this musical genre is determined equally by clearly defined structures and by improvised variations and deviations. Structure and virtuosity merge, and experimentation is an essential part of further development. Thus, in 1967, Gilliam started staining untreated canvases with acrylic paint and then folded, scrunched, and deformed them, gave rise to the Beveled-Edge series, the iconic predecessor of the Drape Paintings. Colors blended, interpenetrated, and formed expressive, abstract worlds of color that were beyond the artist’s control, despite the regulated production process. Bright, partly fluorescent surfaces were created, which Gilliam then stretched onto specially made stretcher frames with beveled edges, giving the series its name.

Sam Gilliam, Untitled, 2020 watercolor on washi 39-1/2″ × 71-1/2″ (100.3 cm × 181.6 cm), paper © 2021 Sam Gilliam / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Gilliam’s early Washington years were formative for his distinctive style. Arriving in 1962, Gilliam was soon working in the context of Color Field painting, which had found its way to the city from New York. He worked alongside artists such as Kenneth Noland and Thomas Downing on the effects and aesthetics of large-scale areas of color. This was the same environment from which the six artists of the Washington Color school would emerge, whose movement would shape Abstract Expressionism until the 1970s.

In the mid-1960s, just as the US-American art of the time was about to reimagine itself in sculpture, happenings, performance, and action art, leaving painting rather neglected, Gilliam took it to a new level by tackling its very essence. « When I did the Drape Paintings, I wasn’t making sculpture, I was reacting against painting, » Gilliam said in 1989. This rebellion within his own field pushed it to its limits and drove his innovative role in US-American painting.

Sam Gilliam, Spring Is, 2021 acrylic on canvas, bevel-edge, 72″ × 72″ × 4″ (182.9 cm × 182.9 cm × 10.2 cm) © 2021 Sam Gilliam/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

While Gilliam’s production processes broke new ground, his works also caused surprise in terms of perception. When hung, the particular edge of the Beveled-Edge paintings and subsequently the sculptural Drape Paintings created an unfamiliar effect that literally stood out against traditional paintings. Much more direct, they invade the viewer’s space and confront them with intense worlds of color. Unlike paintings in the conventional sense, whose extent is predictable and content framed, Gilliam’s object-like compositions in expansive hangings make it impossible to grasp what the painting encompasses. Not only because of their humbling monumentality, but more importantly because of the unruliness that accompanies the liberation from their limitations. They exude the seductive thrill of uncertainty about what has been released with them, and this constitutes the irresistible attraction of the works.

Sam Gilliam has been part of the art world for decades – long before his work was shown at the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017, it was exhibited in the US Pavilion in 1972. But it was only in the last few years that it began to really be received in the context of the social and artistic developments taking place in the US in the 1960s. Gilliam’s individual formal language, which he worked continuously to develop, not only advanced non-objective art, but also set in place impulses for installation art of the following decades. His works incorporate the artistic influences of their time and transform them into something new, timeless, and it has lost none of its impact to this day.

Sam Gilliam’s work is currently on view at Pace Gallery in Seoul, South Korea from 27 May 2021 – 10 Jul 2021.

Ann Mbuti is an art writer and cultural publicist based in Zurich, Switzerland. Her work connects the dots in the arts and culture that form a larger picture of the contemporary.