Our author Elisa Pierandrei spoke to visual artist Massoud Hayoun about his paintings, which aim to stand in opposition to anti-human politics and nihilism.

Massoud Hayoun, Sick of foul, I’ll take the goat, 2024. Acrylic on canvas, 36x48“. Courtesy of the artist. "A meditation on this year of big international elections ."

Elisa Pierandrei: Your acrylic paintings are seen as exploring belonging, identity, and systems of power. Are these topics important in your work?

Massoud Hayoun: People have told me I’m a mess of identities. I’m a middle-class queer Arab American North African man of Jewish faith living in Los Angeles, practically on the edge of all Western-drawn maps. I was raised by my Tunisian and Moroccan-Egyptian grandparents, while my single mother worked very hard to support us. I’m left-handed. The reality is that all of our identities are multilayered and complicated, even those who identify with the so-called majority. I think the otherness of my existence and my work resonates with people because we all occasionally feel lonely or alienated from the halls of power, regardless of our ethnic, sexual, gender, and religious identities.

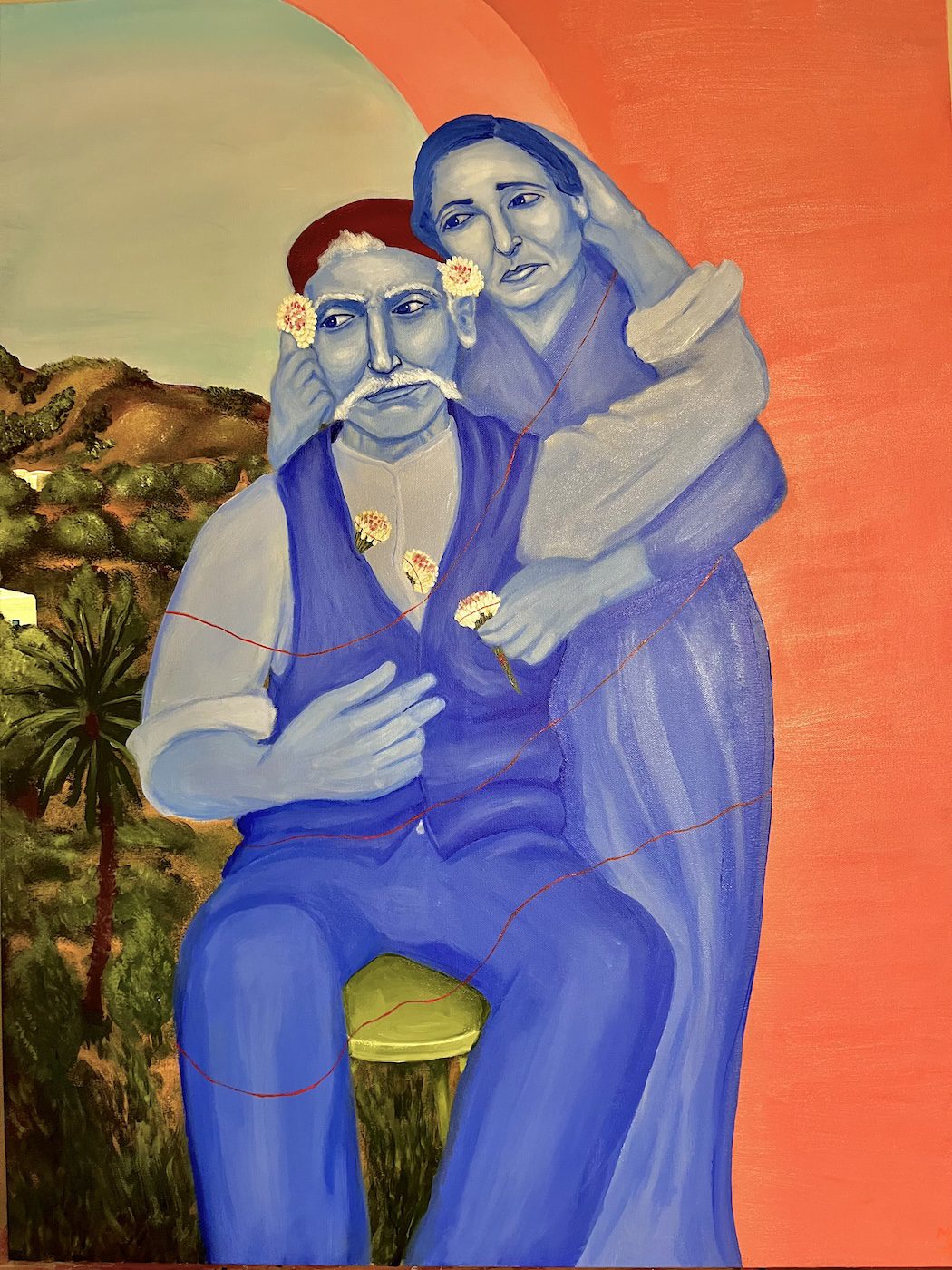

Massoud Hayoun, Alexandria, Momentarily, 2024. Acrylic on canvas, 48×36”. Courtesy of the artist. « This painting is an existentialist talisman. My grandfather, who raised me, was a diabetic Egyptian who loved sweets. When his doctor gave him only a few months to live, we bought him cake, and he inhaled it with the urgency of a man living not in the past or the future. That’s a heavy and a joyous thing. This painting is — / my paintings are — heavy and joyous. »

EP: Do you consider yourself a political artist, and if so what does that mean to you?

MH: Absolutely. And by identifying as a political artist, I’m just saying the quiet part loud. Politics is ultimately about our relationship to each other – particularly to those above and below us in the power structure. Every one of my paintings, even the most whimsical or humorous, is political. A great many artists shy away from explicitly acknowledging the politics and the sociology of their work. I don’t. Art should be accessible to a much broader audience than those who can access education and the time to read about art history and international affairs.

Being a political artist means I work in the tradition of political subversives who’ve come before. Some years ago Ai Weiwei endorsed a novel I wrote about China, and the force of speaking to him over FaceTime added fuel to my practice and led me to finally show professionally. Ai Weiwei describes the role of the artist as a countercurrent to the halls of power. I am that sort of gadfly. My work is frequently nourished by indignation and the need to stand in opposition to anti-human politics and the nihilism of the times.

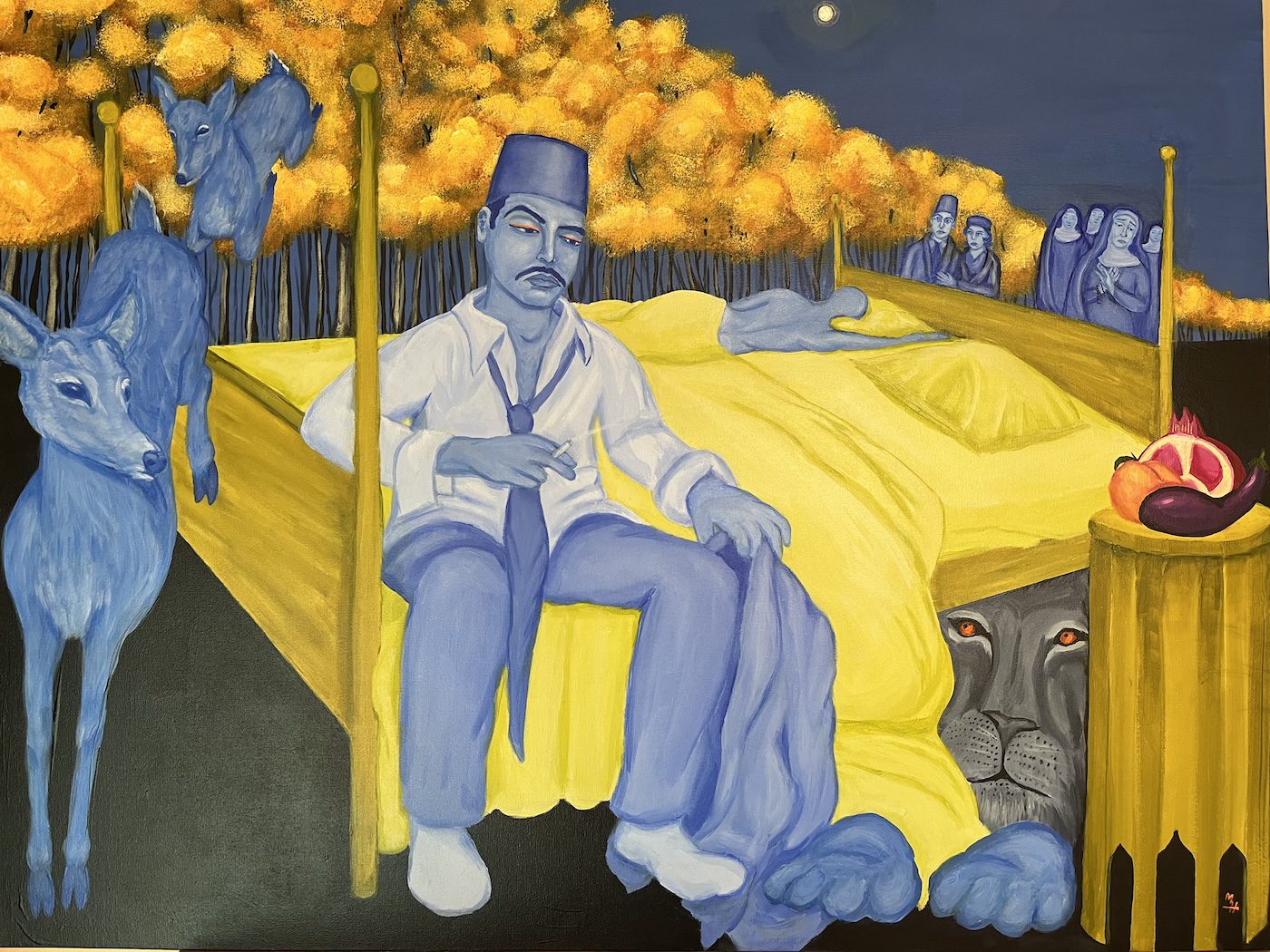

Massoud Hayoun, Bedfellows, 2024. Acrylic on canvas, 36×48“. Courtesy of the artist. « On the complicated act of enjoying life . »

EP: Looking ahead, what new ideas are you eager to explore in your upcoming projects, and how do you see your work evolving in response to the current global (and local) situation?

MH: I’ve painted pieces about the genocide in Gaza and this emotionally exhausting election, among other current events. In those works I’m dealing with brutal realities. Where it is possible – that is to say, not in any portrayal of genocide – to paint my works with a sense of humor and joy, I have. But it’s difficult to create a powerful work that addresses the terror of these times without plunging people further into our collective anxiety and depression. I am exploring new ways to do this and challenging myself to take on pressing topics with a view to uplift rather than to add to the world’s suffering.

Massoud Hayoun, uncynical Tunisian love painting – موسم المشموم. Acrylic on canvas, 36×48“, 2024. Courtesy of the artist. « My great great grandfather was the son of a polygamous Tunisian royal court dignitary. He himself was very monogamous. When his wife, who had a heart condition, died, he declared he would die a year later, and that’s what happened.“

EP: The figurative style of your paintings at times is reminiscent of classic canvases. What elements inform your visual art practice?

MH: I am a figurative artist. People and my interactions with them are the lifeblood of my work – my art and the journalism and writing that preceded it. Were it not for people and my simultaneous love and resentment of them, there would be no practice. One artist who has influenced my work is the Egyptian master Seif Wanly. His work imbues the human form with a great many – sometimes competing – human emotions. There is a melancholy that I find true in the art from Wanly and my Egyptian grandfather’s generation. At the core of Wanly’s work is a profound love of humankind – a desire to understand and to honor it.

Beyond the humans of my works, I use flora and fauna and symbols endemic to my family’s homelands in North Africa to tell distinctly North African and Arab but also universal and accessible stories. I often feel that I am part of a generation of North African and Arab creatives recentering our worlds away from Europe and North America, back to the source. We will be reckoned with.

Massoud Hayoun, Strangers in the night – نعيش في عيون الليل. Acrylic on canvas, 36×36“, 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

« On my way back to my Airbnb from a show in London, I encountered in a public park a large group of men cruising, like our forebears had in the pre-Grindr, pre-legalization of gayness era. I contemplated the reasons for this. It’s possibly the excitement of something so deeply anonymous and illegal. It’s perhaps muscle memory transmitted to us by previous generations. It’s likely a frustration with the dullness of hookups via apps and the Internet. But beyond that, there’s an underlying horniness and loneliness to old-fashioned cruising that is an expression of our humanity in its most undiluted, excessive form. That’s why it’s beautiful and worth honoring.

»

EP: You use a distinct style of bright blue, with touches of red, yellow, and green. What blue painting mean to you?

MH: In the way that poetry can be said to skim all the excess, every element of my works exists for a symbolic, metaphorical reason. Their aesthetic nature is significant but secondary. Colors always represent something, and the people I paint are blue because blue, with its highlights and shadows, is ethereal and ghostly. Most of the people I paint are long dead. Over time, I began to paint everyone in blue, even myself. I recognized that the me of those paintings has always existed in the past, is already gone. The blue people will be observed in the future, but be forcibly of the past.

Massoud Hayoun, Self-portrait with Janes, 2024. Acrylic on canvas, 30×40“. Courtesy of the artist.

« This painting is a meditation on current events in the U.S. regarding women’s reproductive rights and finding my place as an ally in that discourse who is also affected by the patriarchy, the shortcomings of the U.S. medical system in addressing the concerns of people on the margins of power struggles, and the waning separation of Church and State ostensibly guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. The Janes were a radical feminist group that provided safe, illegal abortions to women in Chicago in the 1960s and 70s. After the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court ruling that once guaranteed access to abortions was overturned, many new groups have begun to find ways to ensure that women in affected areas still have agency over their bodies, their futures, and their healthcare.

EP: Your book When We Were Arabs (2019) delves into the erasure of Jewish Arab identities. How has this project influenced your visual art practice?

MH: People have identified with that legacy since time immemorial, but recently there is an endeavor, even among non-Jewish Arabs, to ask what constitutes Arabness in much the same way that people in the Americas are asking what constitutes Latin-ness or Latinidad. I analyzed colonial-era policy documents and other historical texts to answer some major questions for myself.

That book is a starting-off point for what I’ve done since. It influences my work, and yet almost none of my artworks are specifically about the Jewish Arab community. The majority are about the diverse Arab peoples, without a particular focus on any one of our religious or other communities. My work is frequently about Arab femme-ness. But then it is also about masculinity and its undoing.

Massoud Hayoun is an author and journalist turned contemporary artist. Born in Los Angeles in 1987 and raised by Tunisian and Moroccan-Egyptian grandparents of Jewish faith who migrated by way of Paris, Hayoun’s work explores colonization, gender, and marginalized histories. He has had solo and group shows across the US, UK, Morocco, and Switzerland.

@massoud.hayoun

Elisa Pierandrei is a journalist and author based in Milan. Over the years she has gained an interest in the Middle East, Africa, and their Diasporas. She writes and researches stories across art, literature, and visual media. Pierandrei holds a master’s degree in journalism and mass communication from the American University in Cairo (2002) and graduated in Arabic language and literature at the Ca’ Foscari University in Venice (1998).

@shotofwhisky

INVENTER SON PROPRE TERRAIN

More Editorial