An exhibition at the Tate Modern in London, curated by Zoe Whitley and Mark Godfrey with assistant curator Priyesh Mistry, investigates how African-American artists have chosen to engage with Black politics via visually impactful abstract and figurative works.

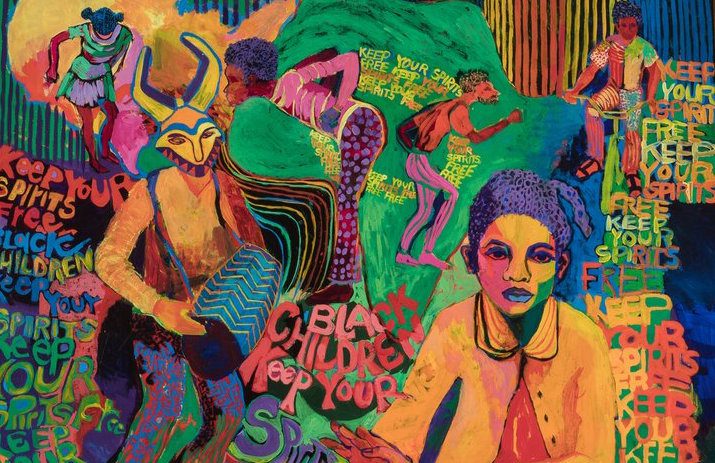

Carolyn Mims Lawrence, Black Children Keep Your Spirits Free (Detail), 1972. Courtesy the artist and Tate Modern.

The exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, on show until October 22, reaches us at a particularly prescient time. Drawing from works made between 1963 and 1983, this complex and multi-layered show raised a question for me that is as relevant now as it was then: what are the stakes for the Black body in the (former) West? Correspondingly, the ways in which artists of African descent in the Eurocentric world have chosen to engage (or not) with the political realities of their time and the formal innovations that might arise from these imperatives form the basis of the exhibition’s curatorial enquiry.

It is divided into twelve sections arranged thematically around individual artists, movements, or self-organized institutions. A significant amount of space has been devoted to ephemera, which enriches the works on display. Groups and collectives such as AfriCOBRA, Spiral, Smokehouse Associates, the Organization of Black American Culture, and the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition are contextualized alongside more familiar names such as Barkley L. Hendricks, Romare Bearden, and Frank Bowling. The result is a keen sense of urgency, in the interplay between the movement for social justice and arts practice (or indeed, art in the service of the movement), conversations between artists and artist-led groups, and responses to critics and friends.

A significant display of educational and propaganda ephemera from the Black Panther Party demonstrates their acute understanding of the importance of visual culture and visual literacy in developing politically active subjects. The Panthers also understood the power of “cool” and the impact of visual signs that circulated within a broader field of images. In contemporary parlance, the Panther “brand” – though not entirely unproblematic in itself – was utilized as a vehicle of the message; there are no empty signs here.

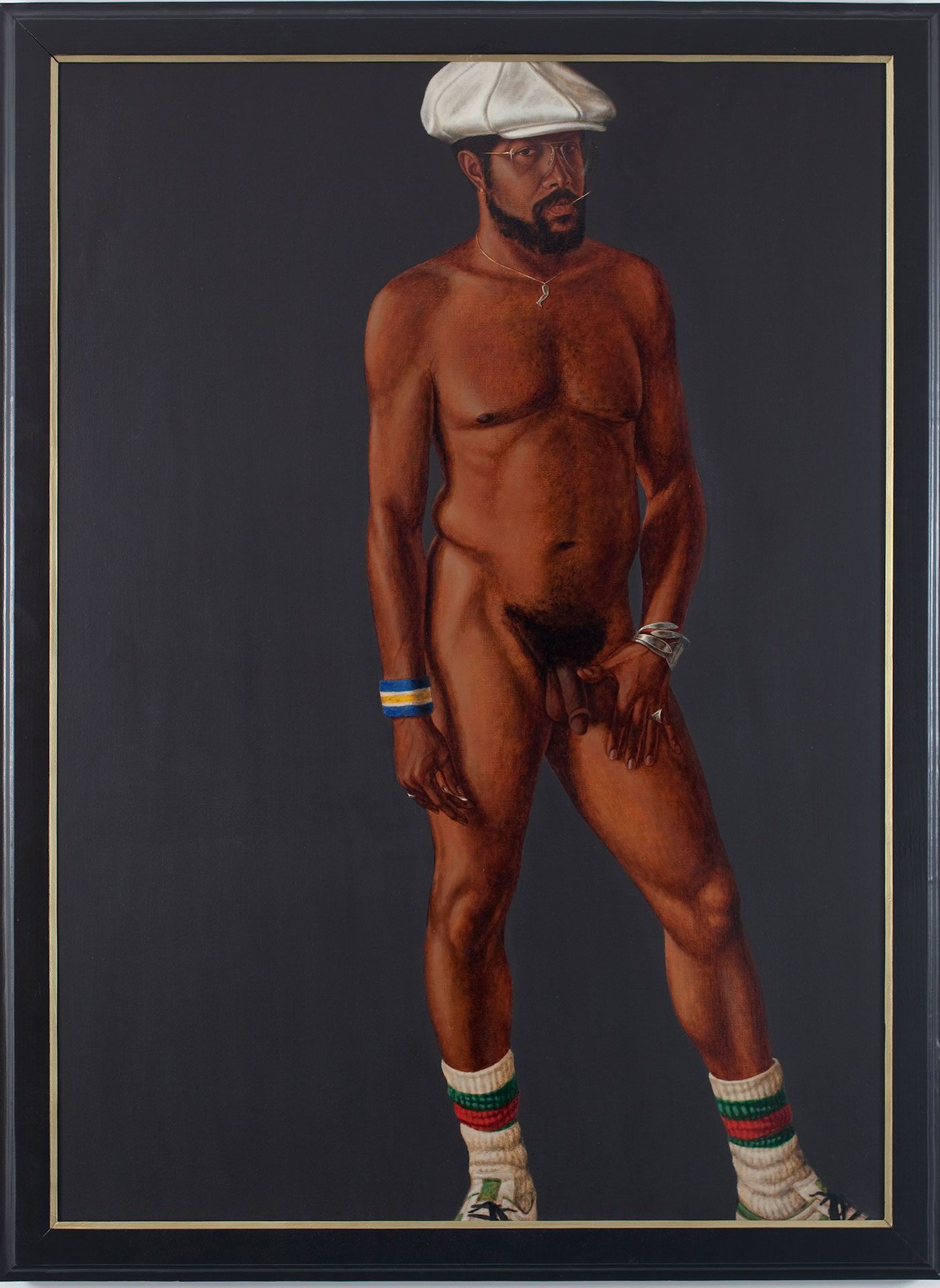

Barkley L. Hendricks, Brilliantly Endowed (Self Portrait), 1977, oil and acrylic on linen. Courtesy the artist.

This subversive embrace of cool is taken in another direction in Hendricks’ Brilliantly Endowed (Self Portrait) (1977), an oil and acrylic painting described by the exhibition label as a demonstration of swagger. Hendricks, naked apart from hat, socks, and shoes, gazes sceptically at the viewer, his left hand on his thigh diverting the gaze towards his penis. The work was made in response to an art critic’s description of the artist as a “brilliantly endowed painter who erred, perhaps, on the side of slickness.” It’s a witty work, a double entendre weaponized to challenge stereotype and convey confidence and self-possession, and the influence of Blaxploitation films is keenly felt.

One can also detect a strong Black feminist undercurrent to many parts of the exhibition with works by Betye Saar, including The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972). A mixed media sculptural work featuring a subverted depiction of the infamously non-threatening Mammy – transforming the docile archetype into an armed and ready revolutionary. Saar has a delightful room of her own, its mid-grey walls hosting a series of sculptural assemblages composed of diverse materials (leather, wood, bones, shells, fur, poker chips) evoking deities, rituals, and power with a masterful formal daring.

Emma Amos’ tender portrait of her child carer, Eva the Babysitter (1973), draws attention to the often hidden labor that allows many women, including the artist, to work. Amos’ contented young child sits at the right edge of the painting, while its subject is to the left, halo–like Afro puffed to perfection. The work’s warmth, empathy, and humanity is emphasized by the yellow-gold tone of the background wall.

Equally pleasurable is Art Is (1983) by Lorraine O’Grady, forty photographs from a series of 400 arising out of a performance during the African American Day Parade in Harlem, where dancers used gold frames to interact with the crowd. The photographs capture the community’s responses to being invited to “become art,” from excitement to indifference.

While the body is well represented, this exhibition also skilfully draws visitors’ attention to the history of abstraction. In light of recent controversies over the use or absence of Black bodies in relation to abstract painting (most notably the controversy of the Dana Schutz painting at New York’s Whitney museum), and the ahistorical suspicion of abstraction as a form of practice that manifest in some of the discourse, it is important that Black artists’ role as innovators in the field of abstraction is given due significance here through the works of Whitten, Bowling, and others.

Lorraine O’Grady, Art Is. . . (Women Crowd), 1983/2009. Chromogenic color print, 16 × 20 in.

Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York © 2015 Lorraine O’Grady/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Soul of a Nation is a superlative work of curatorial scholarship. Thoughtful, thought-provoking, and lovingly curated, it creates space for some often under-represented artists and movements within both their artistic and political contexts, and highlights the ways in which these frames intersect.

As I exited the exhibition, I made my way to the visitors’ comments board. “Black Lives Matter” features on many – the stakes of and for the Black body remain high.

Sonya Dyer is an artist, writer and occasional curator based in London.

More Editorial