The Malawi-born, Johannesburg-based artist creates scenes of the domestic to celebrate the feminine and the unseen.

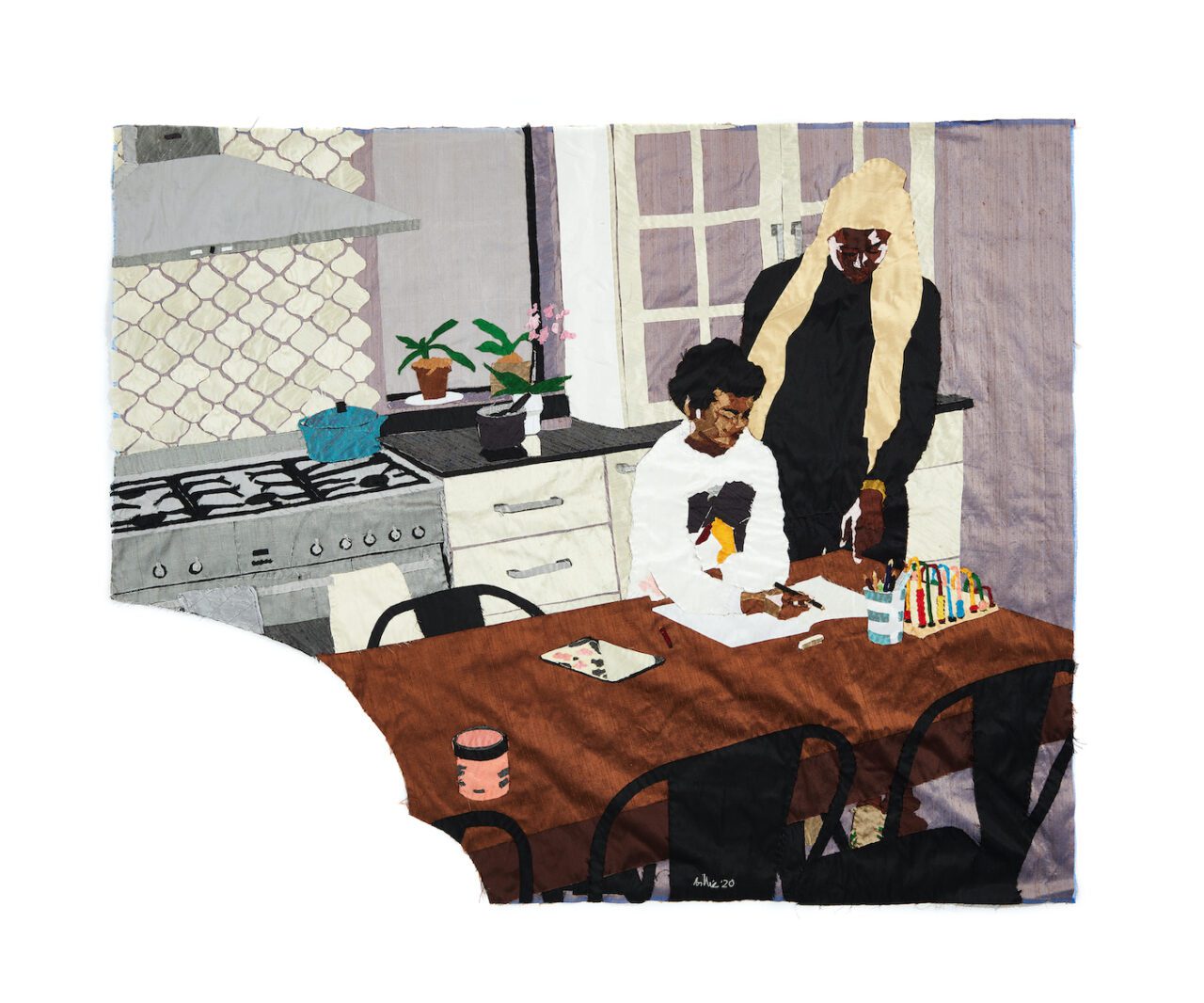

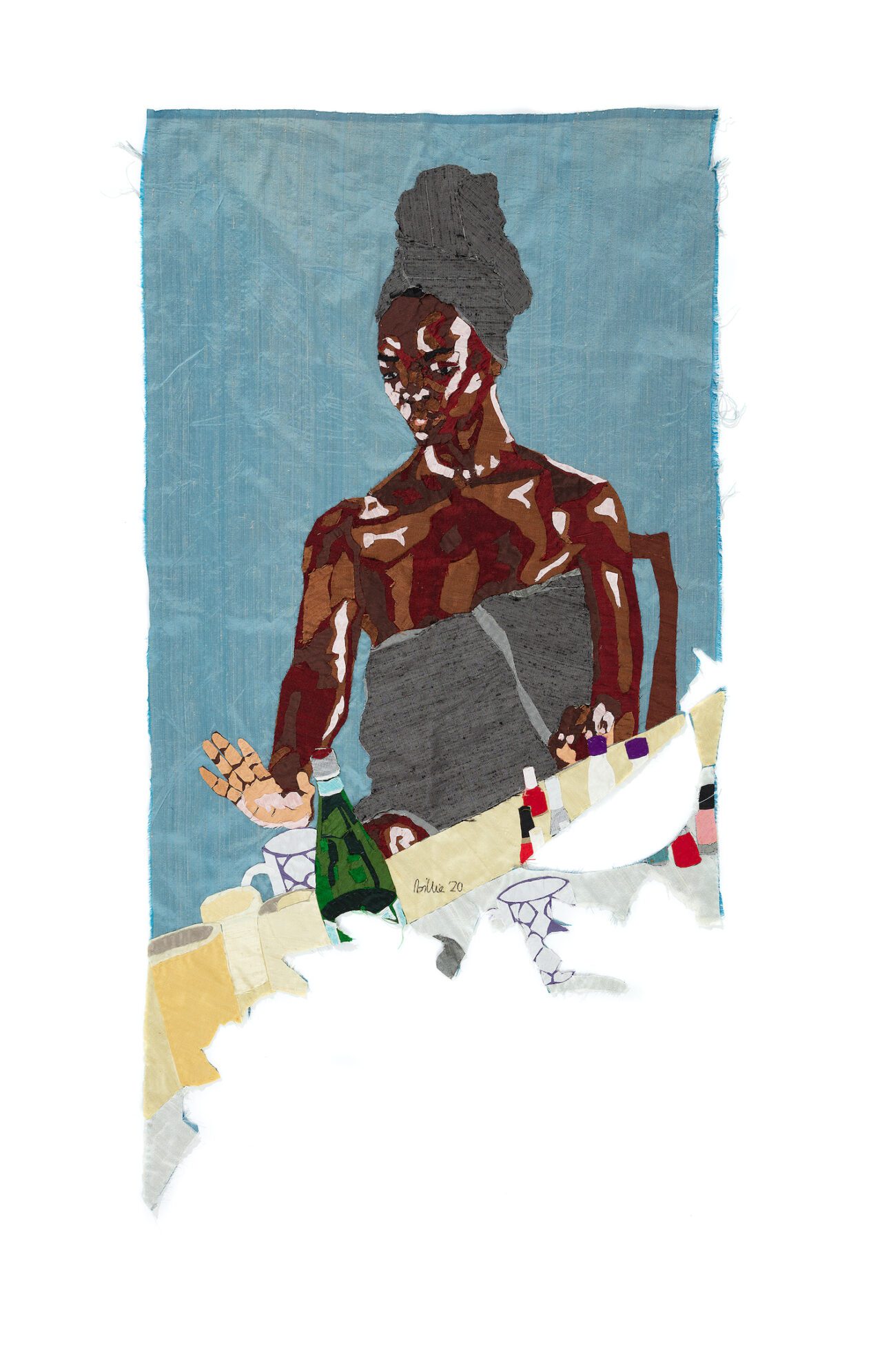

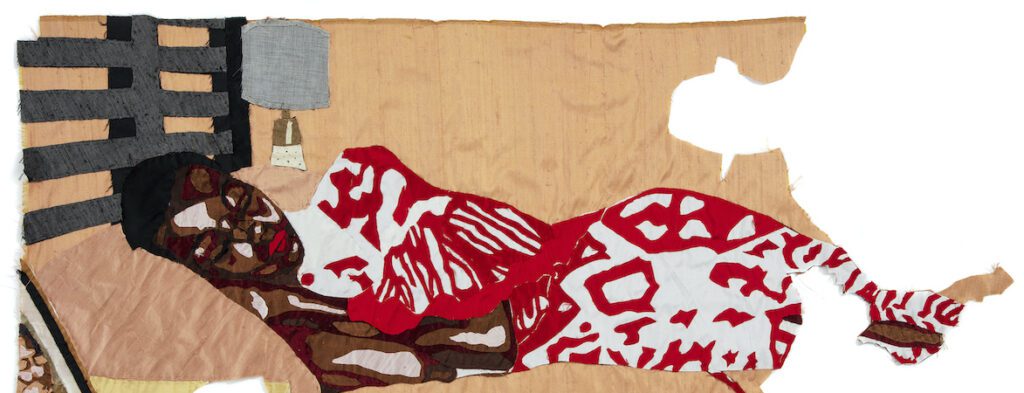

Through her work, Billie Zangewa shares personal memories and landscapes of the home that live in her mind. She collages layers of silk or carefully builds detailed tapestries by hand. Her work is intricate and mesmerizing, textured and dense in color. Although her subjects are everyday moments – people at rest, natural landscapes, a kitchen homework scene – they take on a more meaningful role when we see them as scenes that are often neglected in the broader contemporary art space, scenes in which Black women are the center. This domestic world is one which they have created, and not one imposed on them. The image of Black women as caretakers is one that we are accustomed to seeing in Western modernity, from Manet’s Olympia (1856) to the Aunt Jemima cooking brand; Zangewa’s refreshing take on domesticity, where a Black woman is seen enjoying her Sunday ablutions in Self-Care Sunday or sunbathing in Return to Paradise, is a contribution to transforming the art-historical narrative.

Zangewa’s earlier works depict remembered Botswanan animalsbotanical scenes, or Southern African landscapes. Since the birth of her son, Zangewa has employed the more overt scenes of the domestic to demonstrate her celebration of the feminine and her elevated choice of using materiality so often associated with the mundane or the unseen. Embarking on these more personal histories is a way of illuminating the work of the everyday that is so often overlooked and under-appreciated – the work that allows capitalism to function without pause. Her pieces made during the COVID shelter-in-place period show how our experience of work shifted, and the inequity within modern-day parenting. For women of color, Zangewa is really speaking to the heavy impact that the pandemic has had on the labor force, inside and outside the home.

Her intimate family scenes display nudes in quotidian moments. In Domestic Scene, a couple in the shower form a loving portrayal of bathing together but there is more to it than that. The figure on the right, presumably a man, has his hands up. Made in 2016, this piece might be referencing the multiple times Black men have been killed by police with their hands held high in the air. That gesture, evident in the murder of Michael Brown Jr, became part of the political movement responding to his and the continued killing of unarmed Black people in the US and across the globe. What could be seen as a tender portrayal of a couple takes on very different connotations through that haunting gesture, seen again and again in protests since 2014.

Work that involves textiles, or materials associated with craft more generally, was long regarded as feminine or not coming under the aegis of the contemporary art world. Zangewa embraces both the notion that her work is feminine and that fact that she belongs to a larger community of artists using those materials and techniques to critique capitalist patriarchy and uphold the role traditional feminine “crafts” could have in creating time away from the home, a sanctuary space for women experiencing domestic problems, and a way to speak to personal histories. Art that involves textiles now has a long history of political activism, and Zangewa’s collages belong to the cadre of contemporary artists – such as Shinique Smith, Diedrick Brackens, and Nick Cave – who use varying techniques to speak on Black bodies, visibility, and Black subjectivity.

Zangewa employs a laborious process of sourcing images, sketching them, and transferring that image to fabric through collage. The assiduity needed to re-create images through combining layers of silk appears simple, but is very complex. With silk’s fragile surface, stitching additional layers is time-consuming and prone to the creation of errors. Zangewa plays with materiality as she builds self-portraits and private family scenes that are familiar yet retain an air of disquiet. Scenes that are constructed by such fragile means speak to the tender nature of Black figuration and Black portraiture and to the way they should be held.

Billie Zangewa: Thread for a Web Begun, runs through February 27, 2022 at the Museum of African Diaspora in San Francisco.

Nan Collymore is a writer and an inter-disciplinary artist. She is interested in the body and land, and how the two co-exist. Her work is an attempt at creating a language that re-imagines the body as land and as a corporeal topography. She is the founder of small publishing house L’Habillement and lives in New York.

INVENTER SON PROPRE TERRAIN

More Editorial