In the “post-war” period, many pioneering Black artists were largely neglected by the Western art world despite their significant contributions, and persevered regardless. In the last ten years Western institutions have been waking up to these artists’ legacies. They are finally curating first retrospectives – and of course the markets have followed suit. In this series we chart their careers, highlighting their artistic evolutions and motivations in relation to the world around them. Here, we feature Alma W. Thomas, the first African American female artist to have a solo show at the Whitney, and her sustained admiration for the treasures of the natural world.

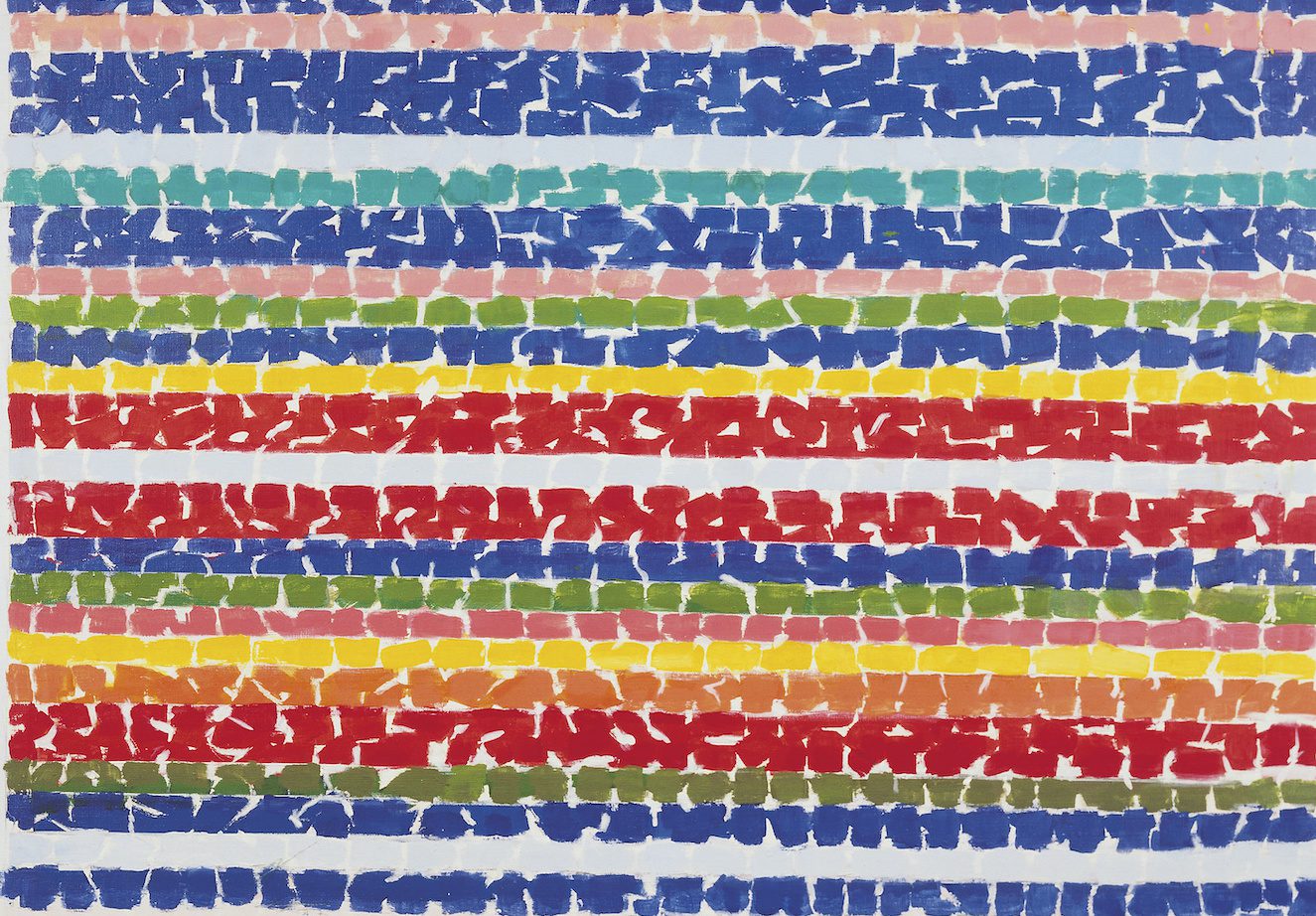

Alma Thomas, Air View of Spring Nursery (Detail), 1966. Acrylic on canvas. The Columbus Museum

In the last twelve years of her life, American artist Alma W. Thomas (1891–1978) pushed the boundaries of abstract art. Driven by a desire to produce works different from anything she had previously seen, Thomas dedicated her practice to challenging her creative imagination. Thomas is renowned for her distinctive dabs of paint, which produce brilliant rays of color across the canvas, a style developed late in life. The artist’s work perfectly captures the vibrancy of the natural world, which captivated her attention. Since her breakout debut in 1966, several major have art institutions recognized the artist’s extraordinary talent through acquiring and showing her works.

Born to two middle-class parents in 1891, Alma W. Thomas grew up in a Victorian-style house in Columbus, Georgia. From an early age, her life in Georgia and frequent visits to the neighboring state of Alabama exposed her to the beauty of nature. In the book A Life in Art: Alma Thomas, 1891–1978 (1981), Merry A. Forresta wrote that the young Alma W. Thomas “responded with uncommon interest and perception to the lush vegetation and the musical sounds in nature that filled [her] surroundings.” Despite these idyllic landscapes, Thomas’s parents sought a better life for their family. In 1907 the family settled in Washington D.C., hoping to escape the racial violence imposed on Black people throughout the American South, and to obtain safety and opportunity. The nation’s capital was legally segregated when they arrived; Black Americans were denied access to most libraries, theaters, museums, and universities.

Thomas was dedicated to her art education and challenging her imagination and creativity throughout her life. In 1924, she graduated from Howard University, the first student to come from their newly created fine arts program. Ten years later, she earned her master’s degree in education from Columbia University. While teaching art in Washington D.C. public schools, Thomas continued to nurture her own artistic interests. In 1948, she joined the Little Paris Group, a visual art workshop formed around Lois Mailou Jones. Its members – art educators and government employees – critiqued submitted artworks and publicly exhibited together.

Alma Thomas, Sketch for March on Washington, ca. 1963. Oil on canvas board. The Columbus Museum

Columbus, GA

In the 1950s and 1960s, Thomas attended art classes at the American University. The painting March on Washington (1963) typifies the artist’s favored style and subject matter at this time. In this work, Thomas depicts a crowd of people in an expressionist form, where bodies and signs are abstracted but still recognizable. The dark hues of blue and red give the work a somber tone that contrasts with her later color palette.

At the age of sixty-nine, after a thirty-five-year career as an art teacher, Thomas retired. From 1960 until she died in 1978, the artist produced her most important bodies of work. At American University she was introduced to the Washington Color School, a group that included Morris Louis, Kenneth Nolan, and Gene Davis. They were known for placing a greater emphasis on color than on form and structure. Thomas drew inspiration from the group’s use of color and geometry to create a new style of her own. Through smaller dot-like applications of paint, Thomas’s works came to project a sense of structure, lightness, and, despite her meticulous attention to placement and color choice, improvisation. With works such as Air View of a Spring Nursery (1966), Thomas expressed a sustained admiration for the treasures of the natural world. This work demonstrates what became her signature style: rectangular spots of bright blues, reds, and yellows create a spectrum of color stretching horizontally across the canvas. Thomas abandoned the defined forms of the landscape entirely to express the liveliness and harmony of nature through her mastery of color.

Alma Thomas, Snoopy Sees a Sunrise,, 1970. Acrylic on canvas. National Air and Space Museum Washington, DC

Her Space Painting series expresses the wonder and thrill of space exploration. As in her works about nature, Thomas’s exceptional understanding and use of color are clear in the work Blast Off (1970). Deep reds and blues are placed against one another on the canvas, creating a sense of tension. In contrast, a strip of light pinks and yellows bisecting the triangle suggests energy and movement.

This new artistic style was evident in Thomas’s first solo exhibition, at Howard University in 1966. The exhibition brought recognition to her creative innovations, but as an African American artist working at a time when Black people experienced discrimination and marginalization within many museums and galleries, there were significant barriers to exhibiting her works in major institutions. With the growing demand for racial equality within the arts and nationwide through the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, attitudes and practices began to shift. In 1972, Alma W. Thomas became the first African American woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. During an interview in connection to the exhibition, Thomas exclaimed: “One of the things we couldn’t do was go into museums, let alone think of hanging our pictures there. My, times have changed. Just look at me now.”

Since her death in 1978, the artist has been recognized through several significant exhibitions, and her work now belongs to collections such as the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the Metropolitan Museum, and the White House Historical Association. Alma W. Thomas’s singular artistic voice, mastery of color, and enthusiasm for life features at the exhibition Alma W. Thomas: Everything is Beautiful on view at the Chrysler Museum through 3 October 2021.

By Leslie Rose.

INVENTING YOUR OWN GAME

LATEST EDITORIAL

More Editorial