Our author Gauthier Lesturgie takes a closer look at Otobong Nkanga's Pursuit of Bling...

Otobong Nkanga, In Pursuit of Bling, Installation view, 2014 / Berlin Biennale © Berlin Biennale

“We are at a moment, I believe, when our experience of the world is less that of a long life developing over time than that of a network that connects points and intersects with its own skein.”1

While on her first journey to Morocco for the Contained Measures of Tangible Memories project (2009–present), Otobong Nkanga (re)discovered the mineral “mica” at an herbalist’s in Marrakesh. This material, which she had already come across once before under other circumstances, brought back memories from a childhood spent in Nigeria. This material then became a springboard for thoughts and tales about her travels and exploits in different cultures and countries.

Although the mica, one of many substances collected by the artist, was intended for Contained Measures of Tangible Memories, it is the main subject for the eighth Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art at the invitation of curator Juan A. Gaitán.

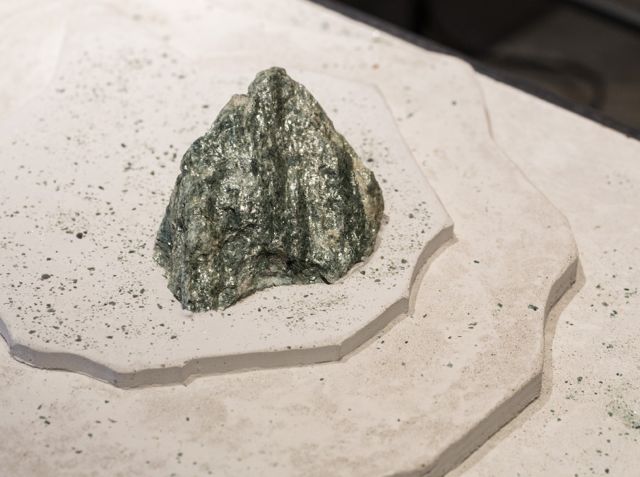

Otobong Nkanga, In Pursuit of Bling, Installation detail, 2014 / Berlin Biennale © Berlin Biennale

The word “mica” is etymologically descended from the Latin “micare” meaning “to shine” or “to sparkle,” an image directly evoked by Otobong Nkanga’s use of the word “bling” in the project’s title In Pursuit of Bling. Mica is a mineral whose flaky texture allows it to take many different forms. Its efficient heat and electrical insulation properties are harnessed in various types of construction and machinery, most commonly in the form of a leaf. It is used in powdered form as part of various types of cosmetic products, plastic materials, and industrial paints. When in its supposed “raw” form, which is more often than not polished and cut to size, the mineral is also used for its aesthetic qualities and in jewelry, items of clothing, and other accessories.

Owing to its incredible malleability and numerous useful traits, the material has been part of various historical, economic, cultural, political, and religious trades over the course of many centuries, which the artist has managed to explore, transform, represent, and connect to his own individuality.

Even at the start of the 19th century, mica was relatively expensive and rare in Europe until its value decreased drastically when large reserves were found in South America and Africa. This decline in price led to intense exploitation in various colonies by Western European countries, generating profound change on geographic, historical, political, economic, and human fronts.

Forming a complex of associations, this progression is created by a constellation of small platforms in black metal of different sizes all linked together. This recurring image in the artist’s work allows her to present a very diverse collection of documents, weaving together the relationships based on the mineral and its history (past and contemporary, collective and individual) in visions of varying clarity. The installation features the mineral itself both cut and raw, sculptures, cards, photographs, cosmetics, video footage of performances, poems, text excerpts, and even “X-rays” of mica plates. This impressive assembly of various mediums extends across the natural resource at the heart of an ingeniously interwoven system.

This accumulation develops vertically around an imposing hanging rug, which represents both the cartography and symbolism of the associated minerals on display around it.

Otobong Nkanga had already put forward her thoughts on the symbolisms of the stone and other ubiquitous elements of our environment during his 2010 exhibition “Make Yourself at Home.” These primal, fundamental elements ultimately created a sense of sentimental familiarity with the artist, no matter their geographies.

It is perhaps this last impression that, for much of her investigation, leads the artist to restructure and dismantle the “common” and “familiar” simultaneously and conceptually in an almost plastic way, opening various extended links.

The artist therefore once again thrives on an intimate and autobiographical intuition associated with remembrance and memory, its absences and recollections.

Born in 1974 in Kano, Nigeria, and currently residing in Antwerp, Belgium, Otobong Nkanga often considers his origins a primary focus of her research. Although far from fatalism, this conscious awareness of the importance of place invokes the theories of Édouard Glissant (1928–2011): “We cannot ignore place, or our own places. I always say that place is unavoidable but it is also unavoidable in the sense that we can’t go around it, we can’t enclose it…. In this sense, we are called upon to recognize all the places in the world, even with our imaginations, because all places in the world are engaging with and confronting one another this very day.”2

In light of this quote, the importance granted by the artist to the memories and remembrance allows her to weave together potentially infinite and ever increasing external associations, as shown by the thinker from Martinique.

As a method of construction of historical study, this approach differs from dominant discussions and accounts. This eighth Berlin Biennale aims to puts forward a nuanced illustration of these specific problems.

After a period of observing the German capital, Juan A. Gaitán is tempted to return, especially in light of current urban developments, to a certain notion of history brought about by previously constructed and established narrative systems. With the Ethnological Museum of Berlin in Dahlem as one of the main venues, the curator and his team have steered clear of head-on criticism, which is often non-constructive, preferring artistic strategies in line with the museum’s aesthetics that interrogate and short-circuit cultural representation. The curator prefers to explore the plurality of connections, methods that describe Otobong Nkanga’s intervention here to a tee.

Deleuze and Guatarri’s valuable notion of rhizome helps us understand the artist’s exhibition as a montage of a network with no beginning, no end, and no center – so essentially a construction of “only lines”3: characteristics that immediately go against those attributed to the story to favor the plurality of relationships.

And yet, one of the videos presented in the exhibition documenting one of the artist’s performances acts as a narration, or storytelling, by embodying another.

Wearing a sculpture made of green stone on her head, the artist positions herself in front of two Berlin churches with green bell towers. A poem in the voiceover tells us about this strange and “unknown” person. Thus Reflections of the raw green crown (2014) leads to a unique discussion about the raw mineral (impersonated by the artist) and its exploitation and transformation in the Berlin urban landscape (here, the roofs of the bell towers). This displacement is clarified by the reference to the town of Tsumeb, Namibia: “I think of Tsumeb, the land of Azutites and Malachite, that must have been where you come from, now empty, for all is gone.” Tsumeb, a mining town, was founded by the German colonial administration in 1905 and was one of the most prolific mineralogical sites in the world to undergo extensive exploitation by European countries. This imagined but well-executed encounter with Germany’s colonial past is revealing and illustrates another essential component of the artist’s creative process, which situates the place of invitation (in this case Berlin) as the first task in her investigation. This is about awareness and the importance of context: “Where am I showing? What kind of space is it?”4

Returning to Édouard Glissant’s philosophy, In the Pursuit of Bling can also be analyzed as an “archipelago” of aestheticism and thinking. Underground processes play a major role in Otobong Nkanga’s work. Édouard Glissant views this concept of intellectual approaches as evolving into a sense of multiplicity, in contrast to “continental” thinking, which views the world as a solid whole and attempts to deliver an “imposing synthesis.”5 In this light, the project presented at the eighth Berlin Biennale comprises a multitude of archipelagos in which the artist manages to unfold different nuances of our contemporary societies, from the mineral to its use, notably in the German context. Illustrating the many travels of one item, mica is itself a pliable material that lends its form to the image of the whole exhibition.

Otobong Nkanga, In Pursuit of Bling, 2014 / Berlin Biennale 8 — 29 May–3 August 2014.

1. Michel Foucault, Dits et écrits (1984), “Des espaces autres” (conference at the Circle of Architectural Studies, 14 March 1967), in Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité, no. 5, October 1984, pp. 46-49.

2. Édouard Glissant, interview with Laure Adler, “L’invitation au voyage”, Cinétévé/TV5/RFO 2004.

3. “Unlike a structure, which is defined by a set of points and positions, with binary relationships between the points and blunivocal relationships between the positions, the rhizome is made only of lines: lines of segmentarity and stratification as its dimensions, and the line of flight or deterritorialization as the maximum dimension after which the multiplicity undergoes metamorphosis, changes in nature.” In Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guatarri, translated by Brian Massumi. “Introduction : Rhizome”, A Thousand Plateaus : Capitalism and Schizophrenia., Minneapolis, University of Minnesota, 1987.

4. Otobong Nkanga, interview with Yvette Mutumba, Salon: The Global Artworld: Focus Africa, Art Basel, 15 June 2013.

5. Édouard Glissant, conference in the frame of the ITM’s seminar : « philosophie du Tout-Monde », 30 mai 2008, Paris, Espace Agnès B.

Gauthier Lesturgie is an independent art writer and curator based in Berlin. Since 2010 he has worked within several structures and projects such as the Galerie Art&Essai (Rennes), Den Frie Centre for Contemporary Art (Copenhagen) or SAVVY Contemporary (Berlin).

More Editorial