L’exposition rend hommage à l’artiste ivoirien le plus important du vingtième siècle et témoigne de son importance dans l’histoire de l’art, écrit Sabo Kpade.

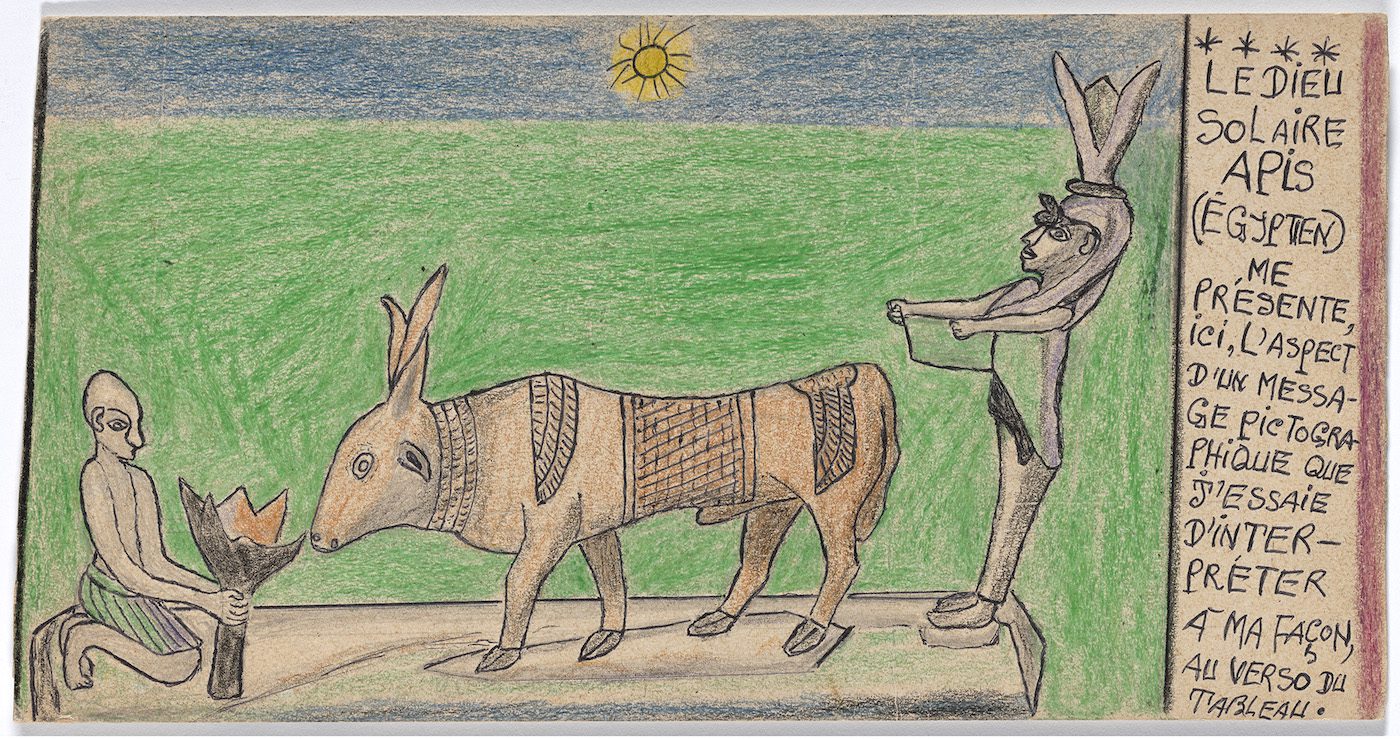

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré. Le Dieu Solaire APIS (Égyptien) me présente, ici, l’aspect d’un message pictographique que j’essaie d’interpréter à ma façon, au verso du tableau from Connaissance du monde. 1991. Colored pencil and ballpoint pen on board, 6 ⅜ × 12 ⅜” (16.2 × 31.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art. © 2022 Family of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré

La production prodigieuse de Fédéric Bruly Bouabré (1923-2014) et ses préoccupations sociopolitiques et culturelles constantes ont depuis longtemps établi sa réputation d’artiste d’importance nationale et internationale. Pourtant, des réticences quant à son manque de sophistication, perçues ou réelles, ont poursuivi sa longue carrière. La simplicité de ses dessins colorés, les objets quotidiens qu’il choisissait souvent comme sujets et le carton bon marché sur lequel il travaillait ont conforté cette vision persistante vis-à-vis de son art.

En outre, le projet de l’artiste ivoirien, qui associait verve artistique et cartographies anthropologiques, a suscité peu d’attention institutionnelle aux États-Unis. Ses nombreuses expositions individuelles et collectives ont eu lieu principalement en Europe et dans son pays, la Côte d’Ivoire. À partir des années 1990, il est devenu une figure familière des importantes études sur l’art africain, ainsi que des expositions internationales telles que la documenta, la biennale de Venise et la biennale de Gwangju.

Installation view of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: World Unbound, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 13, 2022 – August 13, 2022. © 2022 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Robert Gerhardt

World Unbound, la première rétrospective de Bouabré en Amérique du Nord, est une tentative de reconsidérer et de repositionner l’artiste ivoirien comme une figure majeure de l’art africain du vingtième siècle.

Exposée jusqu’au 14 août au Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) de New York, la rétrospective est conçue par le curateur d’origine nigériane Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi. La nomination de Nzewi comme curateur au département de peinture et de sculpture du MoMA en 2019 a coïncidé avec la donation de quarante-cinq œuvres d’art contemporain par Jean Pigozzi, collectionneur italien d’origine française et héritier de la société automobile Simca. Une œuvre clé de la collection est l’Alphabet Bété (1990-91) de Bouabré, une table alphabétique pictographique destinée à son groupe ethnique Bété en Côte d’Ivoire.

« L’objectif de World Unbound est de porter un regard critique sur l’importance de son œuvre », déclare Nzewi, « afin que la pleine mesure de Bouabré soit représentée dans l’histoire de l’art. » À cette fin, la sophistication simplifiée de l’artiste en tant que dessinateur est mise en avant, tout comme le contrôle épistémologique qu’il exerçait sur ses créations de mondes uniques. Cette initiative s’inscrit dans la volonté du MoMA de diversifier le récit dominant de l’art des vingtième et vingt-et-unième siècles, explique le curateur. « Il est également important pour moi de veiller à ce que, lorsque nous accueillons ces voix, elles soient représentées selon les termes de l’Afrique », ajoute Nzewi.

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré. « Ô, Dear black power, if you sit on “world‑trone”, let “God” to lead peacefully your heart, in love of human‑kind of all colour: Aie l’amour de toute humaine couleur!!!! » from Connaissance du monde. 1993. Colored pencil, pencil, and ballpoint pen on board, 11 ⅞ × 9 ½” (30.1 × 24.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art. © 2022 Family of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré

Couvrant cinq décennies, cette vaste rétrospective réunit certains des premiers dessins de l’artiste (Semence de la vie, 1977) et certaines de ses dernières œuvres (La démocratie c’est la science de l’égalité, 2010-11). Ses thèmes sont très variés : scarifications tribales (Musée du visage africain, 1991-97) ; hommage à la féminité (Hommage aux femmes du monde, 2007) ; anciens systèmes de mesure africains (Poids akans pour peser l’or, 1989-90) ; et motifs naturels de naissance et de décomposition (Relevés des signes observés sur oranges, 1998-2008).

Chacun des deux espaces qui composent World Unbound est lié par une œuvre centrale de l’œuvre de Bouabré. Alphabet Bété (1990-91) est un système d’écriture qu’il a inventé afin de transcrire en texte le système de connaissances orales des Bété, son groupe ethnique. La « version œuvre d’art » exposée constitue un ensemble tentaculaire de 449 dessins réalisés sur de petits cartons rectangulaires qui arborent une variété d’images illustrant, entre autres, l’anatomie humaine, des outils agricoles et des produits alimentaires, chacune étant associée à un syllabaire Bété. Dans la deuxième salle se trouve Connaissance du monde (1987-2008), un ensemble de trente dessins à travers lesquels Bouabré traduit des idées et des croyances liées notamment aux notions d’autonomie et de liberté civile. Fruit d’une gestation de vingt et un ans, cette œuvre est présentée comme un projet de vie pour l’artiste, qui documente et retranscrit le monde matériel et les formulations idéologiques à l’aide de son idiome artistique singulier.

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré. « GBRÉ=GBLÉ » N° 118 from Alphabet Bété. 1991. Colored pencil, pencil, and ballpoint pen on board, 3 ⅞ × 5 ⅞” (9.8 × 14.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art. © 2022 Family of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré

L’une des stratégies de Nzewi consiste à présenter l’œuvre de Bouabré selon des regroupements thématiques qui la rattachent à l’ontologie Bété, de sorte que les projections individuelles d’universalisme de l’artiste se trouvent exaltées. Si cette démarche était adoptée en Europe occidentale, où la familiarité avec l’art de Bouabré est plus solidement établie, elle pourrait sembler peu inventive ou audacieuse. Mais en guise d’introduction à un public étatsunien, les regroupements chronologiques soignés permettent d’examiner et d’expliquer les systèmes de croyance ivoiriens et le milieu dans lequel il a réalisé son art.

Nzewi et son équipe du MoMA ont choisi de manifester la « pleine mesure » de Bouabré à travers la création de Digital Bété, une installation interactive qui nous invite à créer des mots et des phrases en anglais, en utilisant les caractères de l’Alphabet Bété. Grâce à un QR code, nous pouvons faire des sélections, aidés par les prononciations de la voix de l’artiste. Une double lecture sur le développement des systèmes d’écriture est subtilement créée par le jumelage de Digital Bété et de plusieurs manuscrits de Bouabré des années 1960 et 1970, exposés dans des vitrines. Le plus enthousiasmant réside peut-être dans le regard privilégié que nous portons sur les débuts expérimentaux de la création d’un univers singulier chez l’artiste.

Installation view of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: World Unbound, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 13, 2022 – August 13, 2022. © 2022 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Robert Gerhardt

Dans World Unbound, les préoccupations plus larges de Bouabré concernant la production de connaissances et la transmission culturelle et, par extension, l’essence même de la vie, sont particulièrement mises en avant. L’exposition révèle un artiste largement incompris et donc mésestimé. Maintenant que l’étendue de sa carrière est substantiellement cartographiée, la réussite singulière de Bouabré peut être pleinement reconnue.

Sabo Kpade est un écrivain culturel de Londres.

Traduit par Gauthier Lesturgie.

More Editorial