Where the White Nile and the Blue Nile Meet

C& speaks to Ala Kheir of the Sudanese Photographers Group, a collective made up of a younger generation of lens-based artists striving for exchange and education in Sudan and beyond.

C&: What brought you to photography? How did all start?

Ala Kheir: That's actually a complex matter. I sought to escape a very intense academic life. And I'm not sure if it was by mere accident, but I found myself doing photography. Even before that, I had done a lot of photography; I enjoyed holding a camera and taking photos of my family and friends. It was in the last year of studying mechanical engineering that I started to take it seriously.

C&: How old were you?

AK: Nineteen or twenty.

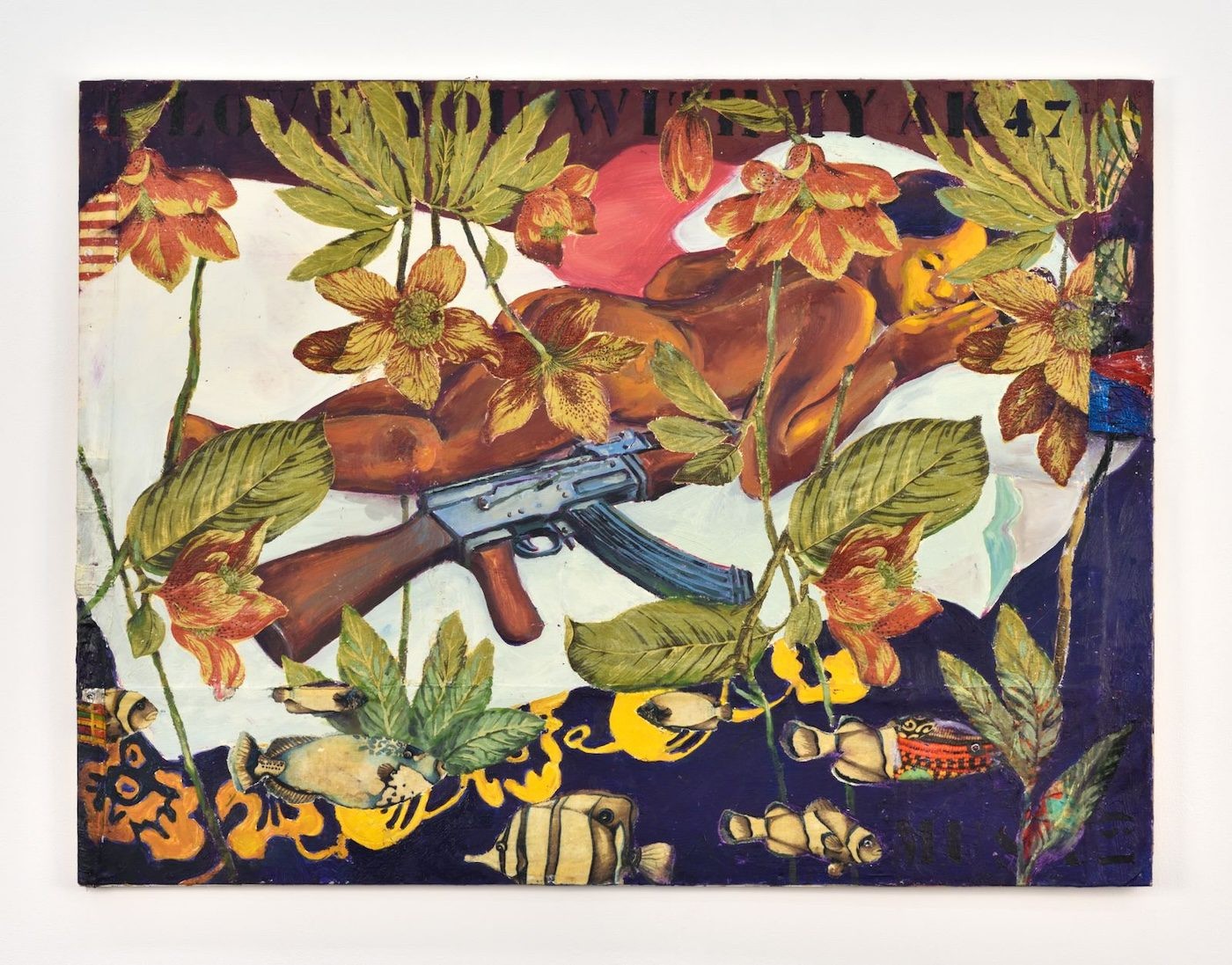

<figcaption> Ala Kheir, Public for Now, work-in-progress, 2011. Photo. Courtesy of the artist

C&: As of now, how would you define your artistic practice?

AK: Well, photography took over. And I would like to do even more. However, in a country like Sudan, I still have to do my full-time job as a mechanical engineer, and this actually supports my life as a photographer. One of the reasons I stay in Sudan is to continue do a lot of photography. I think if I was not in Sudan, I would not do as much photography as I do now. I need a context to which I am closely connected.

C&: Why do you think that if you left Sudan, you would do different things?

AK: Sudan is in a very complex economic situation. Most Sudanese are trying to leave the country for a better job. In my case, a job outside the country would mean going back to only working as an engineer. I would not have much time left to do photography. In Sudan, I am more in control of my time.

<figcaption> Ala Kheir, The Meeting Room, from Along the Nile series, 2016. Photo. Courtesy of the artist

C&: How would you describe Sudan politically and in terms of the contemporary art scene?

AK: The 70s and 80s were the golden age in Sudan, both for art and in general. After 1989, when Colonel Omar el-Bashir came to power by military coup, art was their enemy like any other form of freedom of expression. The attention to artistic expression started to diminish in Sudan, especially photography. Until 1990, photography was the major department in the Faculty of Art and then it was closed and became just a course. The art scene in general is not very vibrant these days and a lot needs to be done to bring it back as it was before. It is a little complicated to do so in an environment where the government does not want photography to grow. There is still that fear of photography. With the revolution of the Internet, now many people have access to education. Most of the photographers in Sudan are self-taught. This is also an advantage.

My friends and I started teaching photography as an art form and we founded a group called the Sudanese Photographers in 2009. It was just a place to meet all the photographers and share ideas. In 2012, we decided to focus on photography and education to promote photography in the country. I am not a classically trained educator but I found myself in this situation of having to teach, and teaching means you have to study more also. We are trying to revive the art photography scene in Sudan and trying to learn, educate ourselves, and transmit to others.

C&: Why does this fear of photography still remain in the country from after the coup?

AK: I think in the beginning of the 1990s, a lot of photojournalists took photos of what was happening in the country. The government reacted against those images that they did not want to be shown in the media. That is how the phobia started. This fear is still here, especially after the Arab Spring, as the regime saw what happened in other countries. When we go on a trip to take photographs, it is very common for us to be arrested and taken to the police station. It is not dangerous, but you lose time, they interrogate you. So they make sure you won't be motivated to go out and take photographs.

C&: Can you name any artists from the golden years in Sudan?

AK:Ibrahim El-Salahi is one of the leading artists from the golden years who had to leave Sudan for the same reasons, that the regime rejected art. He was part of the first generation of artists. But there are also people likeRashid Diab. All those are artists that were very successful in the eighties in Sudan. Most of them left Sudan and never returned, but some of them keep coming and going. That generation represents Sudan's golden age when art was very vibrant in the sixties, seventies, and even the eighties.

<figcaption> Ala Kheir, Untitled, from Khartoum to Addis series during Invisible Borders road trip to addis, 2011. Photo. Courtesy of the artist

C&: What kind of activities do you do in your teaching?

AK: We teach as a collective. For myself, I try to join as many workshops as I can outside Sudan in order to gain something new and increase my knowledge for my own teaching. In Sudan, we offer free workshops, about four each year. And if we get some good funding, we invite some leading seasoned photographers and other experts who are experienced to help us. Other than that, the workshops are usually led by older more experienced photographers who teach younger photographers.

In addition, I work withthe Centers of Learning Photography in Africa (CLPA). This is a project by the Goethe-Insititut that brings together photography education platforms on the continent as a network where we exchange ideas and teaching methodologies and also learn as trainers. So this can be a means to help each other in providing a better form of art education. The best thing is that we have the Market Photo Workshop as a longstanding, leading model. I believe their experiences are very useful to us.

C&: How do you attract your students?

AK: Through Facebook. The Internet helped us a lot to promote our group and also to find funding. We also have our own website now.

<figcaption> Ala Kheir, Mugran Foto Week 2016. Photo. Courtesy of the artist

C&: You also initiated an art festival. Can you tell us more about it?

AK: It is called theMugran Foto Week. The word mugran referce to the confluence where the White Nile and the Blue Nile meet. Mugran Foto Week is a collaboration between theSudanese Photographers Group and the Goethe-Institut in Khartoum. We have always wanted to engage the public with what we are doing in our workshops and Lilli Kobler, the then-director of the Goethe Institut in Khartoum, who we were also collaborating with, supported the idea of the festival. So that was the start.

In September 2016, we had the second edition of Mugran Foto Week. We exhibited results of a workshop series called City in Change that was conducted in 2015 by Michelle Lukidis and André Lützen. It was very intersting to see how the public react to photos of their city.

C&: Finally, do you think art can bring some kind of social changes?

AK: I think art generates awareness, and awareness is the beginning of change in societies. Art can do a lot more, send information and messages in a creative way. It is a tool and it depends on how it is used. And it is very effective sometimes.

Interview by Aïcha Diallo

Education

Nontsikelelo Mutiti Appointed Director of Graphic Design at Yale School of Art

A New School of Architecture Headquartered in Accra

Iniva introduces Sepake Angiama as new Artistic Director

Sudan

Sudan Art Archive Aims to Reclaim a Canon from Afar

Elsadig Mohamed Janka: Liminal Space is a Place of Creativity and Vision