Viva Africa Viva?

With the exception of the 2015 Venice Biennale curated by Nigerian-born Okwui Enwezor, who included a record number of African artists in his themed exhibition, Africa’s presence at the Venice Biennale has been mostly a narrative of absence and underrepresentation, often accompanied by non-official attempts by African curators and scholars to put the record straight. …

With the exception of the 2015 Venice Biennale curated by Nigerian-born Okwui Enwezor, who included a record number of African artists in his themed exhibition, Africa’s presence at the Venice Biennale has been mostly a narrative of absence and underrepresentation, often accompanied by non-official attempts by African curators and scholars to put the record straight. In 1999, The Forum for African Arts was established to increase the visibility of African arts at Venice leading to all-inclusive “African” exhibitions in 2001 (Authentic / Ex-centric curated by Salah Hassan and Olu Oguibe) and in 2003 (Faultlines curated by Gilane Tawadros). By 2007, the then director of the Biennale, Robert Storr, included a call for an official “African Pavilion” in his line-up and despite the manifest absurdity of representing an entire continent in one pavilion – in sharp contrast to the national pavilions of other countries (no less absurd, actually) – it represented an attempt to generate wider African participation in what is supposed to be a show of global art.

Fast forward to 2017 and there is need for a forum once again that invokes its predecessor through a similar sounding title: “African Art in Venice”, a hastily organised event (that proved tricky to get information about, or to attend) bringing together curators and scholars to discuss, once again, the dearth of African artists in Venice. Why? Because French curator Christine Macel has included only a handful of artists working on the continent in her main exhibition (including Abdoulaye Konaté from Mali, Silver Lion winner Hassan Khan from Egypt, Younès Rahmoun from Morocco), and only eight African pavilions made it to Venice.

Abdoulaye Konaté, Guarani (Detail) 2015. Image © Contemporary And

Of these, Kenya, Zimbabwe and Côte d’Ivoire mounted the tried and tested formula of the group show, the former two pavilions curated around themes engaging with the Venice context in mind, while Côte d’Ivoire presents a rather more generic show of artists based on and off the continent.

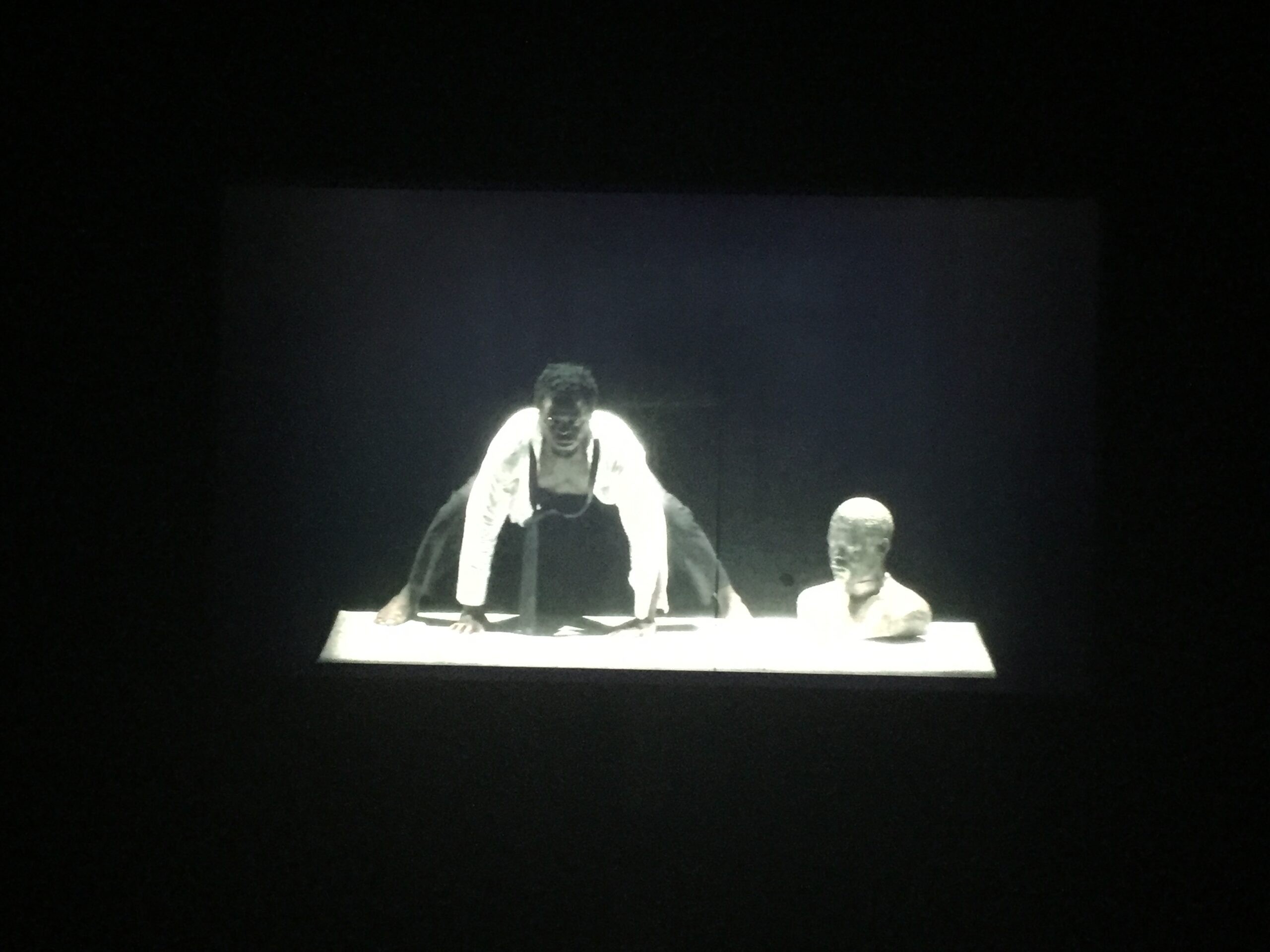

Nigeria, present at Venice for the first time, brought only three artists in a well-produced show complete with color catalogues, printed curatorial statements, and artist interviews. Entitled What about now?, the exhibition made the best of its somewhat random venue by using its three areas to represent past, future and present moments. Victor Ehikhamenor’s trademark sculpted and draped canvases fill the entire first room of the exhibition so that the viewer steps quite literally into the artist’s world of symbols from the shrines and churches of his childhood. The canvases are decorated with miniature copies of Benin bronzes, alternating with little round mirrors, immersing the viewer in Ehikhamenor’s mediation on colonial encounters. Up the stairs is a room showing video work of contemporary dancer Qudus Onikeku set in the present, followed by an installation by Peju Alatise representing the unencumbered dreams of the future of a girl-child working as a maid in Lagos – the easy beauty of the installation contrasting with the horror of the girl’s reality, but also invoking, for me, the still missing girls from Chibok.

Qudus Onikeku, Right Here, Right Now (installation view) 2017. Image © Contemporary And

After a rather weak group show in 2015 due to time and budget constraints, South Africa has come back with a tightly-curated show that “explores the disruptive power of storytelling in relation to historical and contemporary waves of forced migration”. Berlin-based Candice Breitz, a safe choice of an artist with a solid international reputation, addresses the contemporary part of forced migration in an impressively complex work that involves Hollywood celebrities re-telling the personal narratives of refugees. Although the work feels somewhat familiar within Breitz’s oeuvre that often deals with our obsession with media culture, it is an extremely strong work that challenges the viewer on many levels.

Polished, slick and fast-paced, Breitz’s work provides a striking contrast to Mohau Modisakeng’s very personal and poetic meditation on historical displacement brought on by slavery. In his trademark chiaroscuro tones, Modisakeng’s three-channel projection uses images of a sinking boat and various enigmatic characters to chart a metaphorical passage of departure and arrival, set to (what sounded like) a beautiful and contemplative soundtrack. Modisakeng’s work has to compete with the noise levels outside the Pavilion, making the viewing experience of his work less satisfactory than that of Breitz’s – a pity, as these two works could have been more sensitively balanced.

In a year of creeping and suffocating nationalisms, the creation of a Diaspora Pavilion is a particularly effective way of foregrounding global networks and displacement, trans-nationalisms and cross-cultural exchange, creating a contrast to the rather anachronistic notion of national pavilions. Supported by the British Council, curators David Bailey and Jessica Taylor have brought together a group of both established (Sokari Douglas Camp, Isaac Julien, Hew Locke, Yinka Shonibare) and emerging artists (Kimathi Donkor, Paul Maheke, Erika Tan and others) to reflect on the experience of Diaspora. As the participating artists seem to be mostly based around London – I’ve heard the show ironically being referred to as “the other British show” – and clearly indebted to the writings of Stuart Hall, Jean Fisher and other (British) theorists, this on-going project perhaps provides an opportunity to interrogate the particularly British inflection of the term Diaspora.

Dineo Seshee Bopape, mabu/mubu/mmu (Detail), 2017. Courtesy PinchukArtCentre.

Lastly, works by South Africans Dineo Seshee Bopape, Kemang Wa Lehulere and Ghanaian Ibrahim Mahama are also on show in Venice, outside the official election and as part of the Victor Pinchuk Foundation’s Future Generation Art Prize. Bopape, the winner of this year’s generous prize, has installed one of her inscrutable land-works filled with Ukrainian soil, generating associations that linger somewhere beyond words. Along with Lehulere and Mahama, she represents a younger generation of artists able to work on the African continent in local environments that are clearly supportive of their successful international careers.

It is perhaps this point that should be central to any forum on the African presence at Venice: what are the conditions, the collaborations, the networks needed to make it possible for young artists to work and stay on the continent, while maintaining dynamic international careers? The answer may partly be found in the kind of support that brought them to Venice: an important stage to participate fully in the global, while maintaining strong and unique positions in the local.

Based in London, Liese Van Der Watt is a South African art writer and associate editor of C&.

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission