Bill Clarke on the exhibition 'The Unfinished Conversation: Encoding/Decoding' at Toronto’s Power Plant gallery

Sven Augustijnen, Spectres, 2011. Installation view: The Power Plant, Toronto, 2015. Courtesy the artist; Jan Mot Gallery, Brussels. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid

Inspired by Encoding/Decoding in the Television Discourse (1973) by the Jamaican-born, U.K.-based cultural theorist Stuart Hall (1932 – 2014), this exhibition illustrates how relevant Hall’s ideas about the production, circulation and interpretation of media messages remain today. In that essay, Hall analyses how information contains messages the media wants us to take at face value, and argues that we can re-interpret information through the lens of our personal experiences. He also suggests that we can change hegemonic ideas through collective action.

Most of the artists in The Unfinished Conversation: Encoding/Decoding could be considered part of the African diaspora, but considering the show strictly in those terms feels limiting. Rather, the lives of specific people of African descent, including Hall, are used to parse questions of how we preserve alternate histories of world events and make them known, especially when faced with dominant, post-colonial views of history that often exclude other perspectives.

Shelagh Keeley, 1983 Kisangani, Zaire, 2015, Installation view: The Power Plant, Toronto, 2015. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid

1983 Kisangani Zaire (2015), a series of photos by Toronto-based Shelagh Keeley, sets the tone of the show. Images of crumbling Belgian modernist buildings, taken by the artist covertly (since photography was forbidden there at that time), depict a history that continues to inform the country’s ongoing political unrest.

Hall and his ideas are introduced in The Unfinished Conversation (2012) by British artist John Akomfrah. The three-screen projection examines, though Hall’s life, how one’s sense of identity is not fixed but adapts to personal, social or political circumstances. Against a modern jazz soundtrack, Hall talks about his class-conscious family and his role in the New Left movement. Most relevant is Hall’s belief, expressed in a 2004 BBC radio interview, that “another history is always possible.”

John Akomfrah, The Unfinished Conversation, 2012. Collection of the Tate: Jointly purchased by Tate and the British Council, 2013. Installation view: The Power Plant, 2015. Courtesy the artist; Smoking Dogs Films; and Carroll Fletcher, London. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid

Image Keepers (2010) by Zineb Sidera expands upon Hall’s statement poignantly. In it, we meet Safia, whose husband, Mohamed Kouachi (1922 – 1996), was a leading photographer in Algeria. During the War of Independence (1954 – 1962), he captured images of soldiers and civilians, Resistance members (such as philosopher Frantz Fanon), and world figures supportive of Algerian independence, like Che Guevara and Egyptian President Nasser. The Kouachis supported liberation, but Safia claims her husband was never a combatant; taking pictures “was his way to fight.” Safia is now the caretaker of this valuable, but decaying, archive, trying to preserve it with little support. Mohamed’s work is evidence that “another history is always possible”, but Safia’s situation shows how histories become lost.

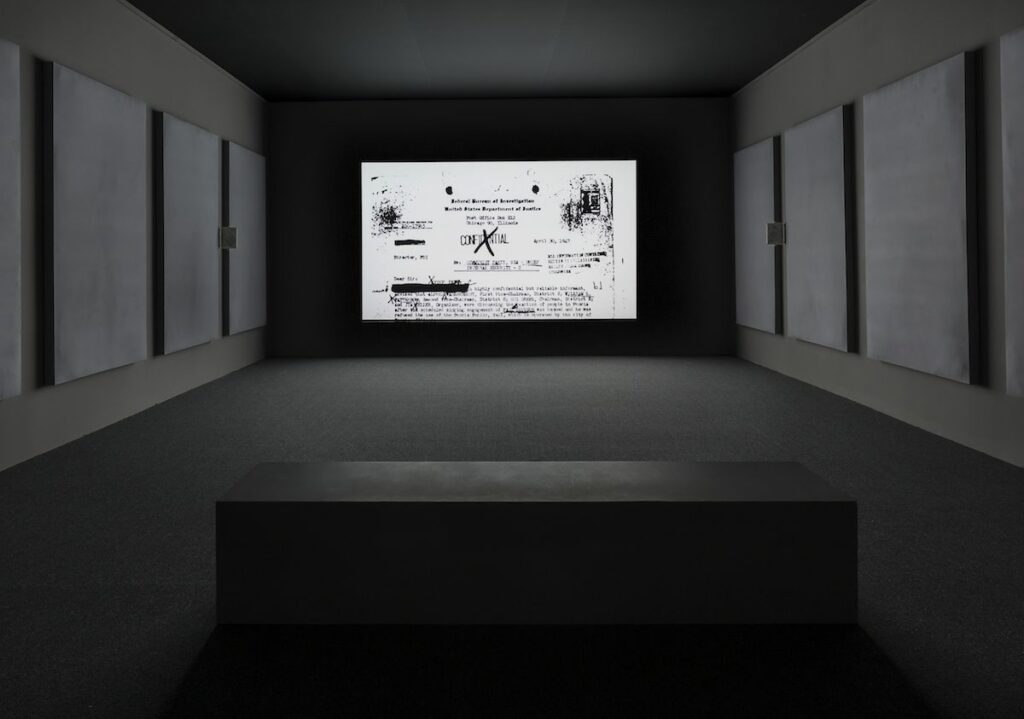

Steve McQueen’s End Credits (2012) is a five-hour scroll of documents compiled by the FBI about the African-American entertainer and activist Paul Robeson in the late-1940s. The video exposes a tool used by governments to rewrite history; in the FBI’s hands, Robeson’s support of “worthy causes” becomes “Communist activity”. Another Black American the U.S. government monitored was Martin Luther King, whose speech Why I Am Opposed to the War in Vietnam (1967) is combined with a Jimi Hendrix performance in Terry Adkins’ Flumen Orationis (2012). King’s oratory reveals truths about America’s involvement in Vietnam, and envisions an alternate history of the U.S. as a “moral example to the world” rather than as a nation succumbing to racism, economic exploitation and militarism. “Our government and the press generally won‘t tell us these things,” King proclaims. “The truth must be told.”

Steve McQueen, End Credits, 2012. Installation view: The Power Plant, Toronto, 2015. Courtesy the artist; Marian Goodman Gallery, New York / Paris; and Thomas Dane Gallery, London. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid

Whose right it is to tell this “truth” is the question raised by Sven Augustijnen’s documentary Spectres (2011). The film’s central figure, Jacques Brassinne, was a high-ranking official in the Belgian Congo when Patrice Lumumba, the country’s first democratically elected Prime Minister, was murdered in 1961. For 30 years, Brassinne conducted his own investigation into Lumumba’s death and published a doctoral thesis on the topic. The film follows Brassinne as he visits others who were there at the time, including Lumumba’s widow. Brassinne seems earnest in his intentions, but he is ultimately a problematic figure – a well-off European writing the history of a culture to which he doesn’t belong.

It is said that history is written by the victors. In Society must be Defended (1975-76), Hall’s contemporary Michel Foucault lectured about the risks of historicism and how the winners in a social struggle may use their dominant position to suppress the losing party’s version of events. Like Hall and Foucault, we must be alert to forces that twist historical narratives in their favour. Because, as is also said, there’s two sides to every story.

.

The Exhibition The Unfinished Conversation: Encoding/Decoding opened on January 24th and is still on view until May 18th at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, Toronto, Canada.

.

Toronto-based arts writer Bill Clarke has contributed regularly to several publications, including ARTnews, Canadian Art, Modern Painters, C Magazine and Art Review. He is also the editor of the online visual arts magazine Magenta.

More Editorial