Our author Gauthier Lesturgie takes a closer look at the work of the Berlin-based Portuguese artist Filipa César.

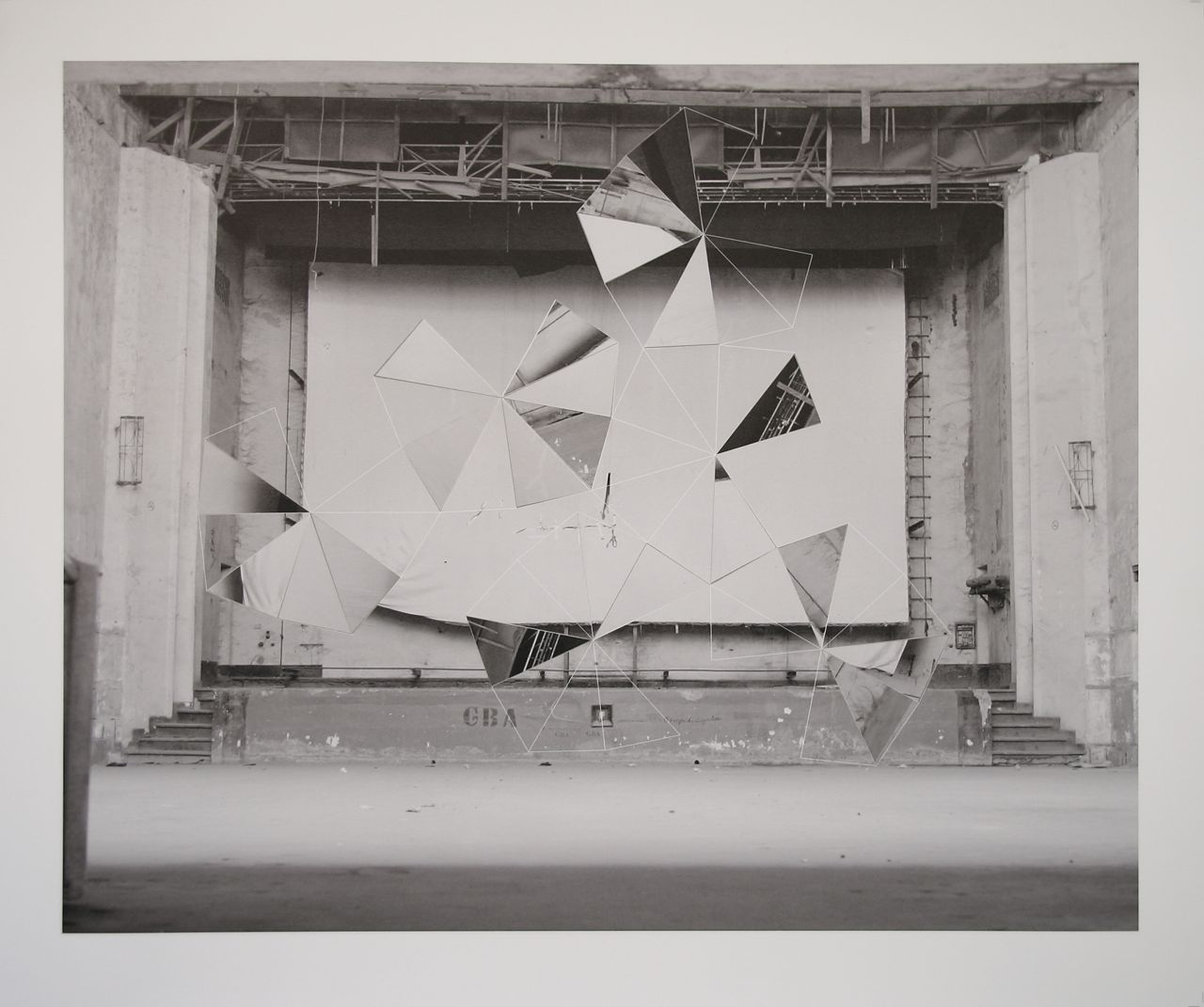

© Cristina Guerra Contemporary Art

“Man fears being engulfed by this mass of words. To safeguard his freedom, he builds fortresses..1”

In October 2012, the Portuguese government launched a “golden visa” program, enabling wealthy foreign investors to receive residency permits for Portugal. The investors obtain access to the European Union in exchange for spending sizable sums in the country. The subtitle Filipa César chose for the exhibition, “or the disposing of the discredited,” denounces the flip side of this “golden visa.”

The Portuguese government’s use of the word “golden” to attract investors leads us to a tangible interpretation of the economy. Taking this physicality as a point of departure, Filipa César interlinks a number of stories, notably the history of mining in Portguese colonies in Africa, that uncover troubling parallels with current affairs.

As explained in a typewritten letter shown at the beginning of the exhibit, the Berlin-based Portuguese artist conducted research in

Guinea-Bissau2 following in the footsteps of her father, who served in the military there from 1967 to 1969.

In her film essay Mined Soil, the show’s centerpiece, Filipa César alludes to Janus, the two-headed deity of Roman mythology, the god of beginnings and endings, passages and gates. While this symbolic figure can refer to the two sides of a border, the drawbacks of the visa and the necessity of considering the historical context, Janus also personifies subversion, a double identity, represented here by Amílcar Cabral, who is also known by his activist nom de guerre Abel Djassi.

A thinker, writer, agricultural engineer, and nationalist political leader, Amílcar Cabral was born in 1924 in Bafatá, Guinea-Bissau, to a Cape-Verdean father and a Bissau-Guinean mother. He studied agronomy in Lisbon, remaining there until his return to Guinea-Bissau in 1952. Until 1961 he worked for the Portuguese government, which commissioned him to compile a report on the state of agriculture in Portugal’s African colonies. His assignment enabled him to travel freely around the Angolan, Bissau-Guinean, and Cape-Verdean countryside. Over the course of his research and encounters with the rural population, he developed a critical attitude towards the colonial enterprise, which led him to cofound the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) with other independence activists in 1956. His work for the government was not solely a cover story, but in fact allowed him to develop an acute grasp of colonial processes in order to facilitate dismantling them. His research during the 1940s and ’50s afforded him a profound familiarity with the agronomic and environmental conditions of the countries and an understanding of their inhabitants. He was one of very few Africans to both study in Lisbon and have direct access to people in rural areas, allowing him to disseminate his ideas. He was assassinated in 1973, six months before the Guinea-Bissau achieved independence.

As he studied the condition of the land, Amílcar Cabral asserted that soil erosion caused or accelerated by human intervention was the primary, if indirect, reason for famine and drought in the countryside. He analyzed the direct relationships between what people were producing, their material interests, and their identities.

Taking after Amílcar Cabral and following his conclusions, Filipa César considers the soil, or in a larger sense the Earth, to be the underlying basis of multiple storylines: a resource to be exploited and profited from, but also an archive of memories. In the film Mined Soil, the sandy soil becomes a canvas for strategic plans. “The soil was the blackboard of the guerilla. Where the tactics of the mission would be drawn and easily wiped out.”

On the walls of the exhibit space, the artist has hung a group of collages called Operations comprising photographs of her research in military archives: schematics of mines operated by the Portuguese army juxtaposed against strategic drawings by the guerrillas of the independence movement. The artist’s aesthetic maneuvers immerse us in her investigations and formally reveal to us the overlap between these different events and uses of soil.

Filipa César uses this material as a clear metaphor for a stratified conception of history: volatile, superimposed layers marked by countless scars in a kind of palimpsest. Mined Soil embodies this concept visually by projecting the video onto the bodies of people reading the various source texts that the artist has collected.Read back-to-back, these quotes juxtapose and weave together the connections with no transitions, drawing together Amílcar Cabral’s research, Kwame Nkrumah’s analysis of neocolonial imperialism, and recent articles from Portuguese newspapers. The current, critical situation paralyzing the “poor” countries of Europe brings these thinkers’ ideas about neocolonialism to life.

In 2012, the Portuguese government launched operations for extracting silver, gold, and other metals in the Boa Fé zone of southern Portugal and authorized mining by the Canadian corporation Colt Resources. Over 2000 years after the Roman army operated mines in the same region, the extraction of materials from the earth exposes cryptic geopolitical issues that Filipa César decodes by referencing diverse storylines and inserting her own voice among them.

.

.

Gauthier Lesturgie is an independent art writer and curator based in Berlin. Since 2010 he has worked within several structures and projects such as the Galerie Art&Essai (Rennes), Den Frie Centre for Contemporary Art (Copenhagen) or SAVVY Contemporary (Berlin).

.

.

1Alain Resnais. « Toute la mémoire du monde », noir et blanc, son, 21 minutes, France, 1956.

2Colonie portugaise de 1879 à 1973.

More Editorial