Rahima Gambo: The Purpose of a Broader Narrative

She started out as a journalist, but as a multimedia artist Rahima Gambo has expanded her range of expression. Her work now reaches from film projects to photo series that reflect the social situation in her native country, Nigeria. With C& author Wana Udobang, she speaks about education, her relationship with nature, and Boko Haram.

<p class="p1">Contemporary And: Sometimes there is an extractive nature about photojournalism, especially when it comes to trauma peddling. Your work subverts those traditions by focusing on other areas of your characters’ identities and lived realities. Did you ever worry about the lack of space for that kind of work?

</p>

<p class="p1">Rahima Gambo: When I was making my first project, Education is Forbidden (2015–16), I already felt very far away from journalism. I was losing a sense of purpose while producing a certain sort of narrative about the Boko Haram conflict that was in demand. A shift and a re-centering started to occur in my thinking, approach, and being, a shift that came very naturally. How others would perceive this change or if there would be space for it was secondary. My first intent for this new approach was for it to be autonomous, self-published, and accessible.

</p>

<p class="p1">C&: There is a certain kind of storytelling that seems expected of an artist who is African and identifies as a woman. Is this something you found yourself interrogating within your artistic practice?

</p>

<p class="p1">RG: I was aware of a certain type of expectation. And perhaps I fall into these expectations. But what matters most for me is that I’m making work that poses questions that I’m continually interested and intrigued by.

</p>

<p class="p1">C&: You have worked in the mediums of photojournalism, video art, and even conceptual art. What has been your process or journey to creating your own visual language?

</p>

<p class="p1">RG: My film project Tatsuniya (2017–ongoing) on Boko Haram wasn’t about an outside audience or observer, or even about producing usable information for the public. It was really about an engagement between myself and a group of girls, about creating alternative narratives together. I feel like the work we made – are still making – is a conversation with ourselves, with our own codes and inside jokes. My series A Walk (2018–ongoing) is also an interior dialogue, but one that I’m having with myself.

</p>

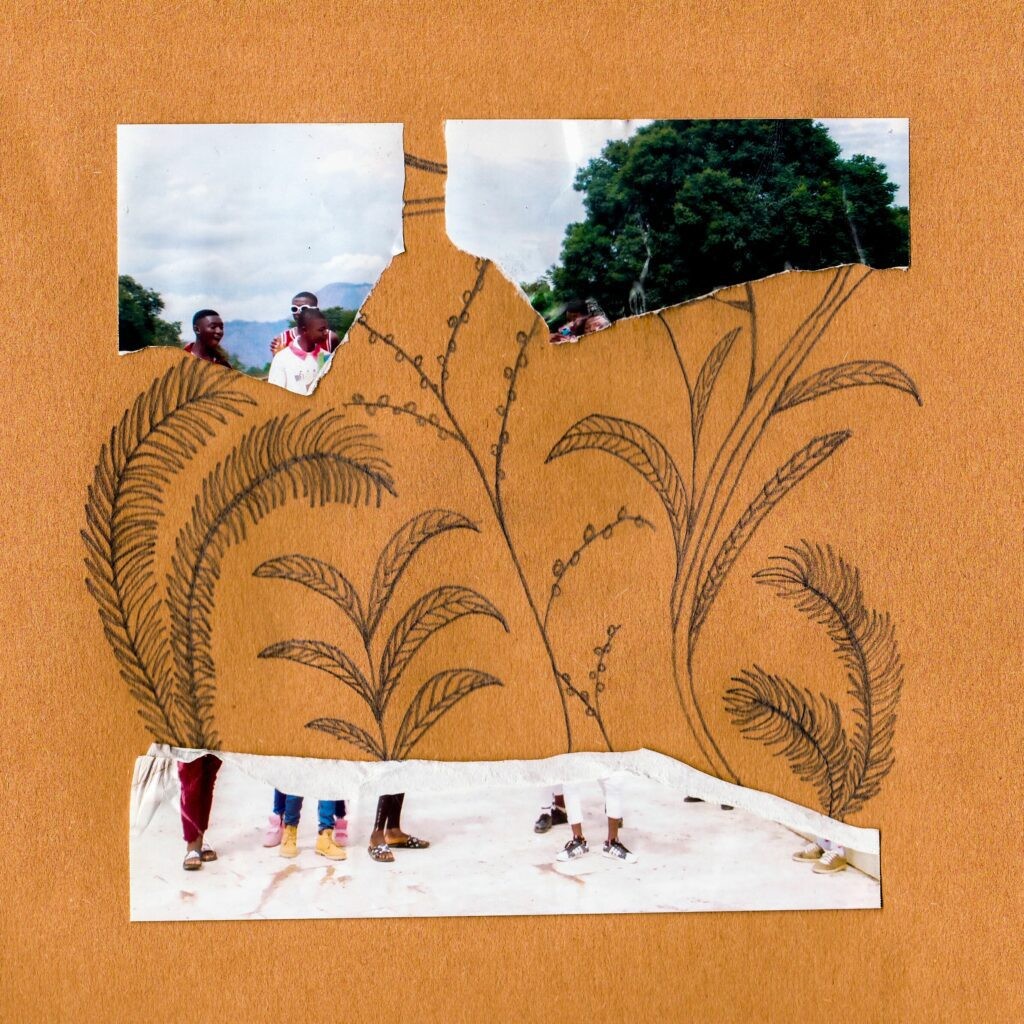

<figcaption> Rahima Gambo - From the project Tatsuniya. Courtesy of the artist

<p class="p1">C&: In A Walk you are documenting the sculptural forms of nature in both still and moving image, exploring memory in materiality, location, and dislocation. What inspired this current work?

</p>

<p class="p1">RG: I began walking obsessively as a daily practice in Abuja, where I live. At first I was walking to figure out things, but eventually the process of walking itself became my main focus. It forced me to be in my body, to be present and engage with my interior and exterior environment.

</p>

<p class="p1">Walking also refers to a specific encounter I had when I was beginning research for a project documenting the increasing use of female suicide bombers in North East Nigeria. I was thinking about the connection between women’s bodies and the landscape. I reflected on the inadequacy of a linear documentary or journalistic style to narrate horrific or disastrous events. And I thought about the possibilities of redefining photography and the narrative visual process for myself, to include my whole embodied present experience.

</p>

<p class="p1">I started to think of walking as a narrative mechanism or tool to approach these questions. The idea that I could interrogate space and experience through the concept of movement, or an action, was an exciting prospect. Walking was a way for me to disrupt and trouble the prescribed ways I had been taught about starting a documentary or photojournalistic project.

</p>

<figcaption> Rahima Gambo 'A Walk' (collage) Courtesy of the artist

<p class="p1">C&: Was the sculptural documentation intentional from the very beginning, or did it come about during the process of the walks?

</p>

<p class="p1">RG: The walk “sculptures” or “contained compositions” came from a place of experimentation. I wanted a way to capture A Walk in the way a photograph becomes a memento or symbolic of an experience, but not quite the event itself. The sculptures became a sort of snapshot of my walking experiences. I did A Walk over an eleven-day period at [alternative art space] The Treehouse Lagos. The plant sculptures I made each day became a slowly decomposing narrative documentation of these walks. The process of walking and picking up, gathering, or planting things, is such a natural action – it’s almost like my limbs knew exactly what to do without much conscious effort.

</p>

<p class="p1">C&: Through a visual stream of consciousness your series also reflects our connection with the earth and its ecosystem. Why do you think this is important in times like this?

</p>

<p class="p1">RG: While walking I was struck by how plants grow and adapt to our urban environments and how we respond to nature. I found myself looking for landscapes that were wild and unconfined by competing city structures. I had a craving to see a sort of pristine wilderness that mimicked a time when the earth was at its healthiest and respected, and treated with awe and even a little fear. When I did encounter landscapes like this, I felt nourished and reenergized by them. There always comes a point during long walks where I feel connected to the world around me. It’s the sort of sensitivity that we can easily lose, a sensitivity we need especially at this time of change and in an increasingly hostile climate.

</p>

<figcaption> Rahima Gambo 'A Walk' - installation view at Treehouse. Courtesy of the artist

<p class="p1">C&: You have used Instagram as a way to curate and share this work, giving it both technological and social elements beyond the gallery. How do you think these elements enhance the project?

</p>

<p class="p1">RG: Walking is such an ephemeral act, it’s difficult to capture its essence long after the walk is over. My mobile phone was a big part of figuring out how to document the project and share the experience with people. Especially because the process of walking is quite solitary and sacred for me. My phone happened to be the only tool I had with me when I first felt inspired to document a moment.

</p>

<p class="p1">A walk is also very much about the improvisation and impulsivity of moving through a space that is slowly revealing itself to you for the first time. The sculptures I made while walking would often be left behind as a sort of “offering” to the environments that I traversed, if I couldn’t bring them back with me. Instagram was the perfect platform to highlight the instantaneity of that concept.

</p>

<p class="p1">Rahima Gambo (b.1986) is a Nigerian photographer and artist whose work focuses on the everyday to social issues that looks critically at notions of documentary storytelling. She came to artistic practice through photojournalism and has been working independently on long term work that breaks away and questions it’s frameworks. Gambo uses her work to ponder on her environment, identity, history, memory, freedom, escape, healing and the spaces in between these things. She is interested in the long-term processes of documentary storytelling working with other forms such as drawing, video, sculpture and installation to trouble her narratives.

</p>

<p class="p1">Wana Udobang is a Nigeria-based freelance journalist, poet and documentary filmmaker whose work is at the intersection of women’s rights, social justice, healthcare, climate change, culture and the arts.

</p>

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas