Neelika Jayawardane, Africa is a Country Culture and Arts Editor, visited Bamako for this year’s Encounters Biennale of African Photography.

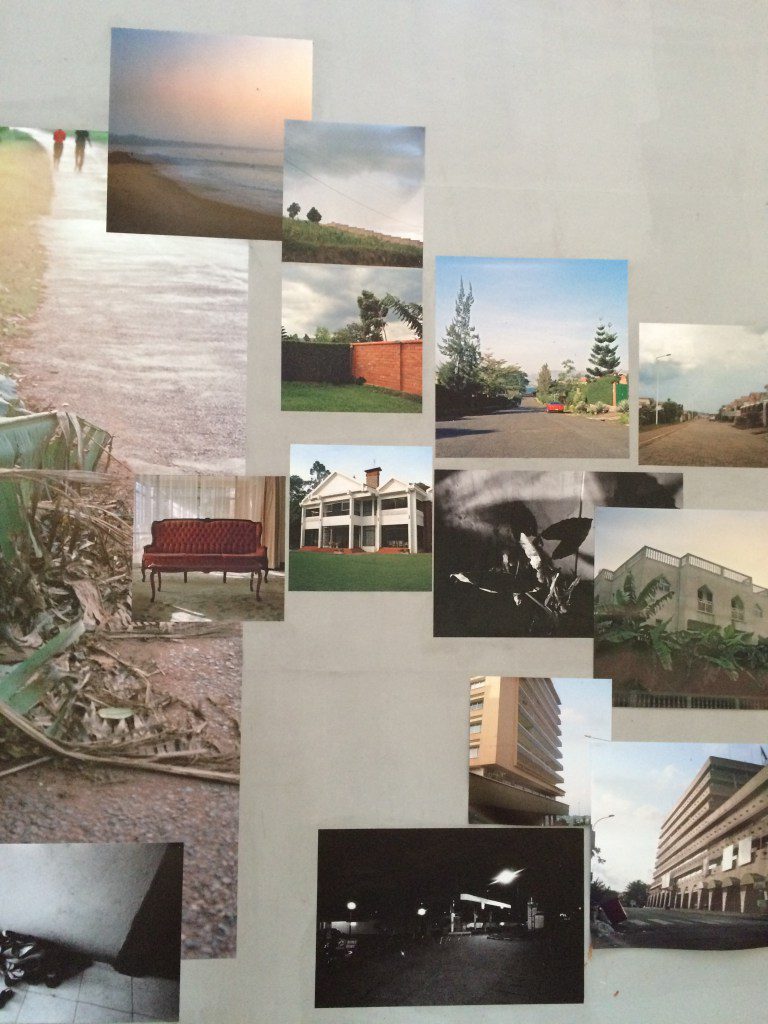

Mimi Cherono Ng'ok, Do You Miss Me? Sometimes, Not Always Installation view, 2015, Rencontres de Bamako. Courtesy Africa is a Country

In 2015, the tenth edition of the Rencontres de Bamako – Biennale of African Photography (popularly known as Bamako Encounters) returned to the global stage, self-aware and mindful of its relevance to the process of re-building Mali’s national unity. The overarching theme of the Biennale, “Telling Time”, meant that we focused our attention on the imperceptible presence of temporality in photographs – on the relationship between time and the photograph, between the self and the passage of time, and perhaps even the fragile bond between self and nation. To that end, Bisi Silva and her curatorial team selected a range of lens-based artists who had experience in documentary, performative, and conceptual photographic practices. The thirty-nine artists whose work is shown in Bamako work with all the innovative possibilities that the technology of photography and lens-based artwork offers us today, from old-school developed film to digitally manipulated collages, video work juxtaposed with still frames, stills from re-enactments of iconic Hollywood films, and fantasy vistas projecting Afro-futures.

Any photographer can tell you that the strictures of being successful – or trying to get there – include near-constant travel, jetlag, and aloneness: residencies, promotional talks, openings at galleries, art shows, festivals. One lives out-of-place, and out of time, performing a presentable, palatable version of self. Given these disjunctures in modern photographers’ lives, I wondered what it might mean for them to be engaged in “telling” time, Bamako Encounters’ theme, using a medium that is, essentially, about distilling time into a “still”. In stilling a moment in time through recording it in an image, we are engaging in a form of melancholia – an inability to let go of a past as time moves on. Our longing for that past is strong enough that it sometimes appears in our mirrors, and in frames of photography and film – uncanny visitors from histories we cannot untie from the threads of our present.

Some of the most powerful work at the Bamako Encounters remarked on the way that past attachments stay ever-present, using deeply personal reflections, meditating on the way that time – and the geographical, political, and genetic locations through which we have passed – keeps telling and retelling itself on our psyches and our bodies. Mimi Cherono’s collage of photographs, the first to greet the visitor in the cool, white exhibition tent, comments on that relationship with time in a way that is more indicative of melancholic presence – an inability to let go of a past that insistently wounded one’s present. Cherono’s work, Do You Miss Me? Sometimes, Not Always is an invitation, a secret garden of jewel greens overlapped by darkness and dappled light. “Do You Miss Me” consists of a selection of photographs taken in Kigali, Abidjan, Kampala and Nairobi, images of both cityscapes and suburban loneliness. They were taken during six months of travel, subsequent to the passing of one of Cherono’s close friends, South African photographer Thabiso Sekgala. These studies tell us stories of cities built by architects influenced by poor-man’s Bauhaus and post-colonial practicalities: minimalist, concrete, easily replicable. But Cherono also bookmarks structures that hope to escape that mediocrity, aspiring to something to do with indicating affluence: a white home with a double peaked roof, its white columns holding up twin stories, accompanied by an immaculate, close-cropped green lawn. In another photograph, a red brick wall shows us the perimeter of a property and the limits of its inhabitants’ freedom; an ornate, russet settee, devoid of a sitter, tells one just how uncomfortable this aspired-to comfort is. Shoes – heeled court shoes, kiddies’ sandals, and some fashion-conscious youth’s sneakers with Velcro tongues – are piled up at an entryway – awaiting their owners’ return. A red sports car barrelling down a wide avenue, past sleepy conifers and hedges, is reminiscent of Americana; a seashore with a couple walking in the distance could be a postcard: one of them is wearing a red shirt, the other is dressed in dark clothes, and their feet are catching the silver web of saltwater lapping the strand. The largest image in this collage is a close-up of banana leaves – broken and battered by rainstorms, some ragged by age, others choked by the undergrowth. Between them the head of a dirty white pony figurine – perhaps once part of a carousel – is poking out.

In the middle of that refulgent foliage and the decaying objects Cherono has imbedded a small, blurry black and white image: it is a photograph of a man who is either just waking up or feeling a little tired because it is late at night. The small shadow by his elbow indicates artificial light and therefore it is probably night. His slim body is lounging comfortably on a sofa, his elbow placed on a cushion, his head resting on his right hand. He smiles from some far-away place, already part of a history we are forgetting. But that smile-that-is-not-a-smile, more mysterious than that of any European Renaissance beauty, keeps hauting us.

Many photographers attending this Biennale had heard about Sekgala ending his life only a year before. Mimi and he were friends and collaborators on photographic projects; in fact, it was through Mimi that I learned of Thabiso’s death in October 2014. Looking at this image of a man who seems to be already fading into the undergrowth of an unkempt garden – symbolic of his blurred memory – I am immediately reminded of Sekgala and our collective narratives surrounding his absence. Yet, I wondered about the effectiveness of imperatives admonishing us to remember the past as an elixir against forgetting.

Other photographers interacted playfully with the presence of the past and the way that powerful cultural regimes imbed themselves into our imaginary. In Plantation Boy, Uche Okpa Iroha presented a series of photographs in which he inserted himself into stills from “The Godfather” films, appearing sometimes as a character in the background – a guest at a wedding, a silent witness to negotiations between members of la famiglia – and sometimes actively taking part in the action – intensely in conversation with a detective taking down the license plate details of a car, and bringing a bouquet of white tulips to a recently killed character, slumped over the steering wheel of a car.

Here, Iroha complicates the ubiquitous presence of the U.S. movie industry, i.e. Hollywood, on our collective imaginary: in his re-enactments of these iconic films, he “stills” them for a moment in order to make himself – the boy from the “plantation” – part of the narrative. In so doing, he makes us realize that we are not simply passive recipients of the imprint of the geopolitical west, but subaltern participants who speak back, act up, and insert ourselves without waiting for an invitation.

Monica de Miranda’s exploration of the impact of colonial-era and contemporary migration on the genetic and psychological strands of our bodies also works with shadows and disjunctures – but here, rather than depicting rupture through shadows, the artist illustrates the way in which violent breaks in our distant and not-so-distant histories reverberate in the present. De Miranda’s work comments, specifically, on what it means to be a part of post-colonial Lusophone communities – fewer in number than British or French colonies, strongly tied to their former colonisers through a shared language, violently enforced Catholicism, and genes. Unlike Britain, France, and the Netherlands, Portugal had a history of encouraging intermarriage with the colonised other in order to “improve” and civilise them.

During the two years it took for de Miranda (Angola/ Portugal) to do the research for her multimedia work, Once Upon A Time (2014), she travelled to and filmed her life in the post-colonial Lusophone communities in Angola, Cape Verde, Portugal, Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), and London (England). Her overall project includes video and several other media: an installation, a website, and a photographic series. De Miranda interrogates, through these multiple formats, what it means to embody transnational and transcultural identities – what it means to be a part of the metaphoric and geographic locations of Europe and Africa, and of Portugal and Angola in particular. At the Biennale, the photographic triptych Falling is affixed to a wall adjacent to a dark interior space where her video work is showing. Falling shows an abandoned ship rusting on a seashore and a woman wearing a white Grecian robe lying on the border between saltwater and sand. She is lying on her side, facing the ship, taking in the presence of this large, disused body.

The image of de Miranda’s body draped on the seashore with the rusting hulk looming in the background is so beautiful that one may be tempted to remain standing there. But the sounds of the ocean and seashore – ship’s calls and lapping water – beckon one into the dark room exhibiting de Miranda’s video work. “Once Upon A Time” includes a three-channel video, significant sections of which are shot from the inside looking out – often to the sea – showing views from the windows of de Miranda’s living spaces in different geographical locations.

De Miranda’s work is as intensely personal as it is political; in a way, it is a meditation on an unrequited love: this is the relationship that we – those who embody a multitude of home-spaces – have with our symbolically and psychologically significant, yet often uninhabitable, origins. They are homes that unhome us, though they are evident in the makeup of our bodies and our collective cultural memory. Rusted and leaking as it might be, we are dominated by this history; it looms like a hulking vessel, just out of reach, rusting into the ocean separating our realities and our longings. There is an ocean’s worth of yearning here.

M. Neelika Jayawardane is Associate Professor of English at the State University of New York at Oswego, and an Honorary Research Associate at the Centre for Indian Studies in Africa (CISA), University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa). She is Culture and Arts Editor at Africa is a Country.

More Editorial