Antwaun Sargent: Tearing Down Borders Between Magazines and Museums

18 September 2020

Magazine C&

Words Will Furtado

8 min read

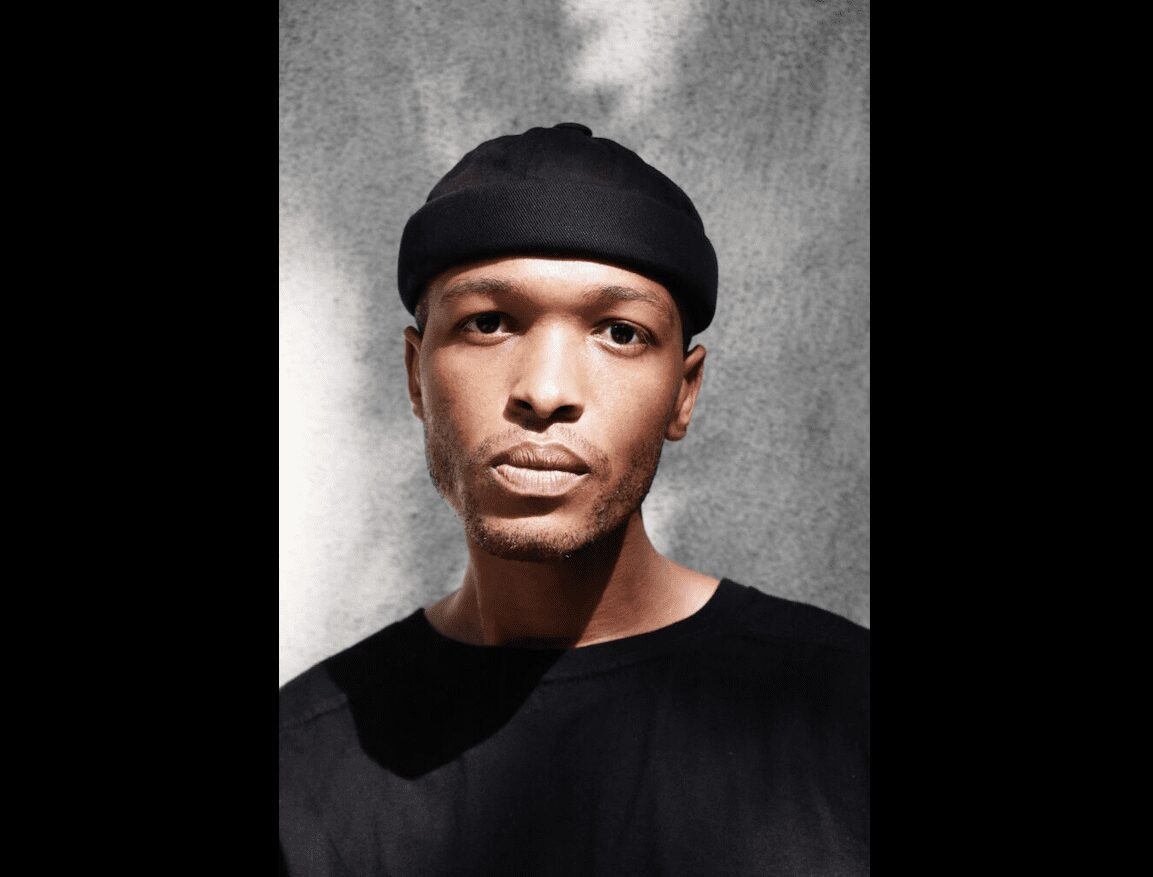

Still fresh from publishing his first edited photography book, The New Black Vanguard, Antwaun Sargent has curated the exhibition Just Pictures at projects+gallery in St. Louis, Missouri. We spoke to the New York curator about his international selection, and images that exist between the conceptual and the commercial.

Contemporary And: Could you talk me through your selection process?

Antwaun Sargent: With this generation you have to engage online, because that’s where many came to understand pictures, encounter photos, and exchange images. For me, also, there are no traditional gatekeepers there, there are no editors there, there is no directing traffic there, there are no curators directing what’s in and what’s out. So it allows for certain possibilities. And one possibility is that borders can be transgressed. National borders, borders between, say, art and fashion, borders between conceptual and commercial, borders between the magazine and the museum. You know, all of these borders become fluid.

And so to me this exhibition was always going to be a sort of international conversation. It was important to make sure that the artist selection reflected how we encounter engines, irrespective or regardless of national borders.

Joshua Kissi, When Kids Play, 2019. Courtesy the artist.

C&: So the online has been your primary mode of discovery for this show?

AS: There are artists I’ve encountered online, but there are also artists, like Joshua Kissi, who I’ve known for ten years. There are other artists whose works I first saw in a more institutional or gallery setting. It’s a mix of ways of coming to notice artists or know their work. It’s a mix between traditional and nontraditional spaces, like social media. They’re both super important ways of discovery, and I’m not interested in a hierarchy between them.

But then there’s also another organizing principle. With The New Black Vanguard, I started a conversation around young photographers from the African Diaspora. And all of these image makers are part of that Diaspora. You have Renell, who has roots in the Dominican Republic, Mous Lamrabat, who has roots in North Africa, Yagazie Emezi, who has roots in Nigeria, Ruth Ossai, who also has roots in Nigeria but also but grew up in London. It’s a real reflection of young photographers across the Diaspora. And not necessarily about social media or museums. Because these artists flow in and out of those spaces. It acknowledges the ways in which they have been able to circumvent and use these spaces to make sure that their images are being seen and making sure that their concerns are being grappled with.

Arielle Bobb-Willis

C&: You mentioned images situated between the commercial and the conceptual. What is the particularity of image creation in that space?

AS: I think the traditional art world separates the commercial from the conceptual. There’s a traditional photographic history that tries to say, well, this is the artwork and this is the commercial work. I think there’s something in allowing artists to push back against that distinction – this is all of my work and you have to grapple with all of it. There’s just something a little bit more honest in that.

But there are also other things. So you think about the Pictures Generation, Douglas Crimp, and how they were poking fun at advertising and using ads and sort of cockily available images to think about networks of desire and power. That’s now infused in the making process of these young artists. They are no longer outside of the making saying, “look at this, look at how advertising is affecting the way in which we perceive ourselves.” They seamlessly make that critique in their work by using the power of advertising in the language in which they create their images. Then they put it in museums and put it online, and in each of those contexts it comes to mean something different. That’s the power of these images – whatever space they show up in, they take on a new meaning. For example, the cover image for The New Black Vanguard is from Tyler Mitchell’s photographs for Vogue – a beauty ad and a lipstick ad. But you don’t get that on the cover of Vogue.

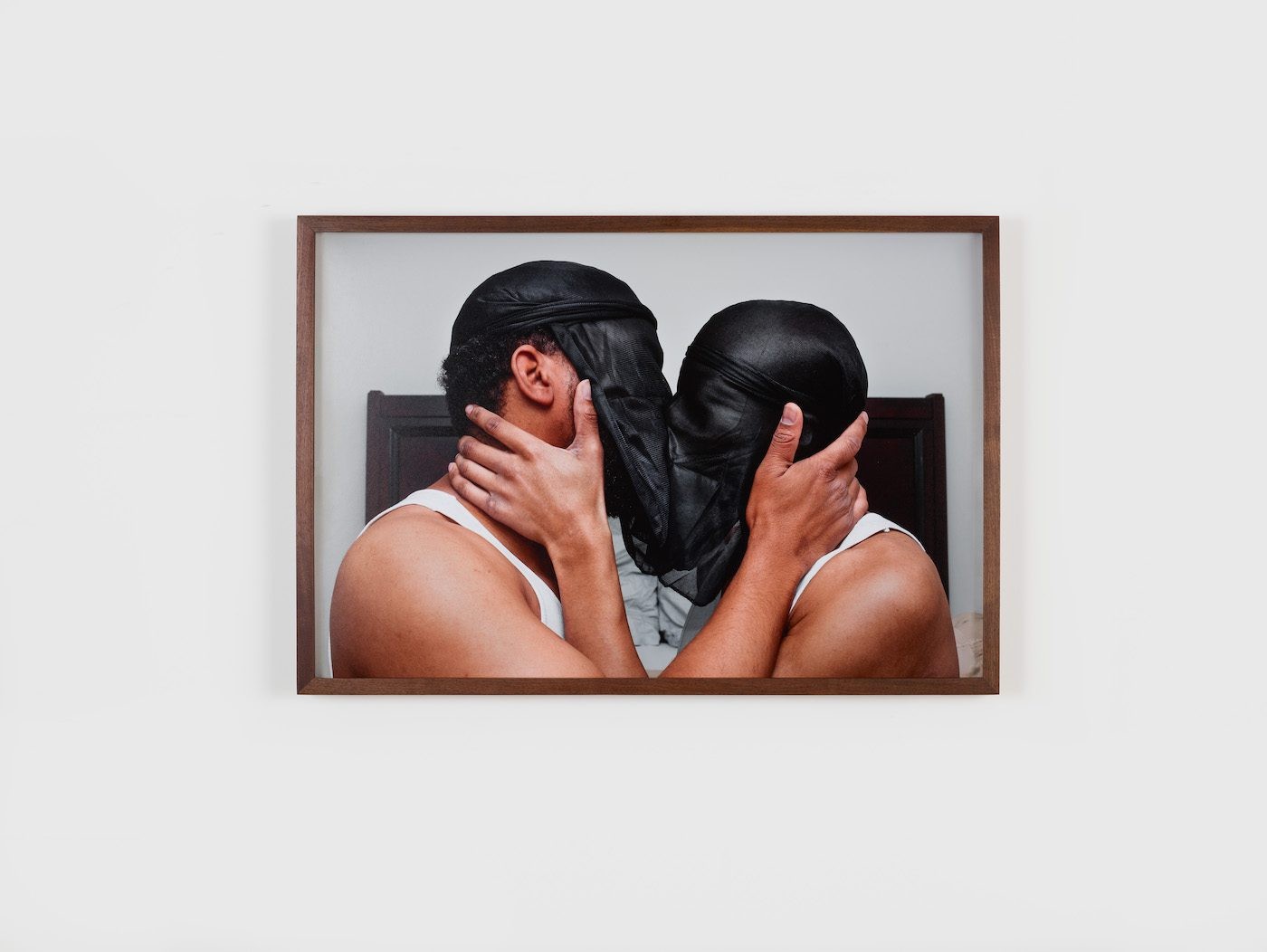

Justin Solomon, Things We Carry, 2019. Courtesy the artist.

Some of these conversations are conversations I started with TheNew Black Vanguard and wanted to further explore. The show is a series of personal works, none is for a brand or advertiser. It expands to include others in this idea that I call the New Black Vanguard. You have new photographers like Justin Solomon, who is St. Louis-based and thinking about shadows, about desire within friendships and really beautiful silhouettes. An investigation of identity, but through a more abstracted stir-up traction. And Arielle Bobb-Willis, who is thinking about the body and about twentieth-century painters in relation to her photographs, like Jacob Lawrence.

So in the blurring of conceptual and commercial, artists just make the images they want to make, while pulling references and inspiration from their own lives, but also our history and the history of photography. All of those things collide in their images, making them a very rich text to read.

Ruth Ossai, My Heart Is Clean, Lagos Nigeria, 2018. Courtesy the artist.

C&: The collaborative complicity between the artist and the model is quite present in this exhibition, often creating new visual possibilities. How do you think dynamics between artists and models have been changing in recent years?

AS: Once upon a time, you walked onto a set and just did exactly what the photographer told you. And now there is a bit more collaboration. Ruth Ossai, for example, often shoots her family, and they often get free rein for what to wear and things like that. But I also think it’s important to understand that the camera is control. Ultimately, the person behind the camera is the person in control. Of making those images. And they are the real authors of those images. And so while there has been a shift in how images are made, allowing for a bit more collaboration, in terms of authorship, you know, I’m showing the work of eight artists. And they own those images. I think it’s important to think about collaboration in their practices and how that is a generous act, but at the same time it’s often within a vision that they set. I don’t want to say that there’s an equal relationship between subject and photographer because there isn’t one. And historically, there hasn’t been one. Ultimately, these image makers are expressing their desires and they’re exerting their power and their agency over photography, which is wonderful.

Joshua Woods, Black Power, 2019. Courtesy the artist.

C&: Can you tell me more about your upcoming projects?

AS: In the same week that this exhibition opens, a book I edited comes out: Young, Gifted and Black: A New Generation of Artists. It features a whole group of artists who have emerged over the last decade, from Eric Mack to Jordan Casteel to Kevin Beasley to Johnathan Lyndon Chase to Jennifer Packer and their immediate predecessors. That book is really about a generation of Black artists who are making their imprint on contemporary art. That was a very fun project because it arose out of a private collection – the Lumpkin Boccuzzi collection. Two gay men who live in New York, who I know and who collected this work over the last decade, really becoming patrons and supporters and champions of these artists. That’s so important because we often don’t think about how art ends up on the walls of museums, or who the people are that help artists when their work isn’t yet in vogue. Who truly believed in them and helped them not only financially, but also in terms of connections with curators and so on. On the one hand it’s the story of a generation of artists, but on the other hand it’s a story of how the sausage gets made.

Yagazie Emezi, Lilith, 2020. Courtesy the artist.

It’s important that the art world be a lot more transparent about how artists come into museums, but also the consciousness. Very often, and before museums would collect Black artists, there were Black patrons who did the work of making sure that that work was understood and valued and collected and preserved. Which allows artists to move into the mainstream. That sort of quiet nourishment when the lights are not on you. I wanted to do the project to make sure that one of those stories was being told, but also these are artists that I came of age with in New York by large. When I first started writing, they were at the beginning of their careers too. As I have grown as a writer and a curator, these artists have also grown right alongside me. I’ve been engaged in their work for the last decade. So in some ways, this is a capstone of my youth and their youth in New York.

Just Pictures is presented byBarrett Barrera Projects at projects+gallery in St. Louis, US, until 21 November 2020

Interview by Will Furtado.

from

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

from

Antwaun Sargent

Antwaun Sargent Appointed Director and Curator

Intersecting Patronage, Family and Community with Bernard Lumpkin