Still a Powerful Platform for Critical Dialogue around Art, Ecology, and History

Haja Fanta takes a look at the long-awaited biennial, questioning its conceptual coherence while admiring its composition and drawing out its continued importance.

The trajectory of this year's Dak’Art Biennale has been far from straightforward. On 25 April, just three weeks before the event’s scheduled opening,it was postponed to November 7. The press release cited “the determination of the new authorities in charge of the sector to organize the Biennale in optimal conditions, commensurate with its scope and reputation as a historic rendezvous for the world's art lovers.” Discussion ignited across social media, with many speculating that the decision stemmed from Senegal’s recent change in leadership.

Tribute to Anta Germaine Gaye. Installation view at 15th Dakar Biennale. Photo: Haja Fanta.

Most importantly, the eleventh-hour rescheduling left the OFF program, a cornerstone of Senegal’s independent and grassroots art activity, with little time to adapt. Yet true to its origins in artists' resilience and self-determination, the OFF persisted, with participants rallying under the hashtag #TheOFFisON and delivering a dynamic program. The OFF has always thrived amid uncertainty. And now, the rescheduled biennial coincides with13th edition of Partcours, a program of exhibitions and events at thirty-three spaces, established by curator Koyo Kouoh and ceramicist Mauro Petroni to cultivate a point of engagement with Dakar’s art scene beyond the usual Dak’Art schedule. Together, the effect is that the IN, the OFF, and Partcours have enveloped visitors and locals alike throughout the year.

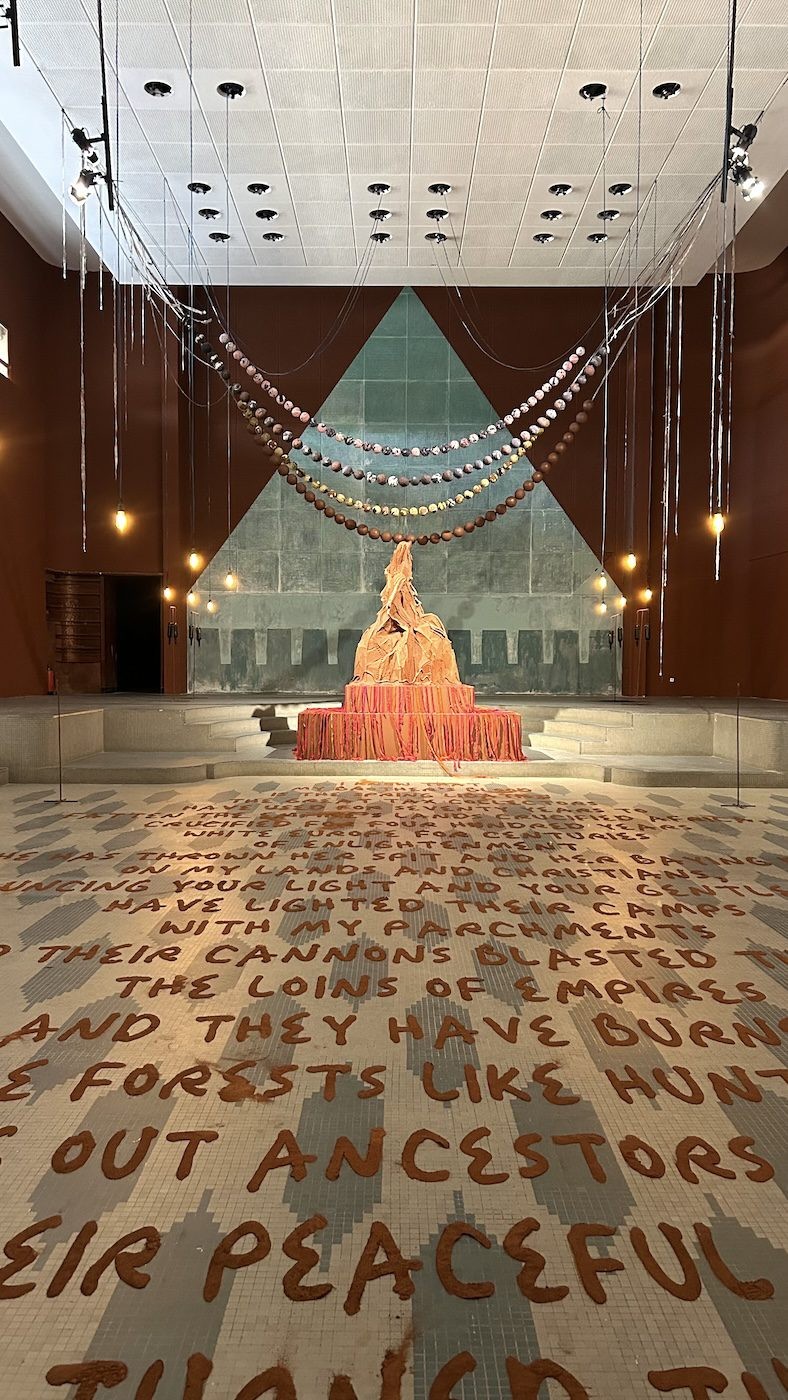

Wangechi Mutu, A Palace in Pieces, 2024. Installation view at 15th Dakar Biennale. Photo: Haja Fanta.

Under the artistic direction of curator, art critic, and composer Salimata Diop, this year’s Dak’Art is titled “The Wake,” Xàll wi in Wolof and Le sillage/L’Éveil in French, and brings together fifty-eight artists from across the African continent and the Diaspora. Borrowed from Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016), Diop has explained, the title takes on three main meanings: the ripple effect left by a boat moving through water, a funeral reception, and the state of awakeness. Diop adopts Sharpe’s framework as methodology and lens to focus on how the histories of Black life continue to unsettle our present and future realities.

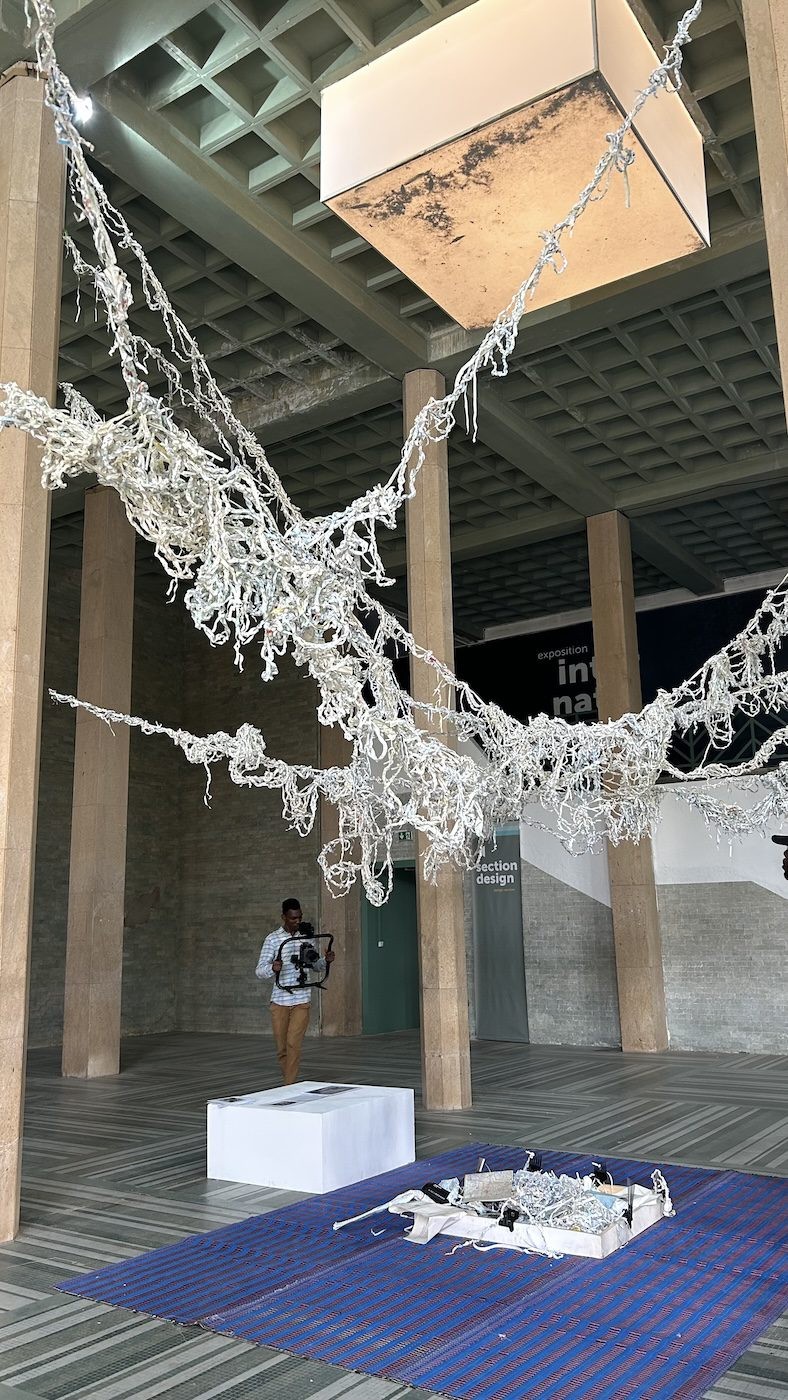

Sonia E. Barrett, Map-lectiv, 2024. Installation View at 15th Dakar Biennale. Photo: Haja Fanta.

Against the backdrop of a city unafraid to confront pressing social and political questions – as evidenced by recent mass protests in response to the conviction of opposition leader Ousmane Sonko – it is fitting that Diop brings such an urgent inquiry. The ideas manifest vividly in British-Jamaican artist Sonia E. Barrett’s sprawling sculpture Map-lective, for which she collaborated with women in Dakar to braid colonial maps disrupting Eurocentric notions of how the world comes together. The work challenges fixed ideas of geography, posing multiple questions. One being: what would treating maps as constantly shifting mean for our climate crisis?

Gina Athena Ulysse, For Those Among Us Who Inherited Sacrifice: Rasanblaj!, 2024. Installation view at 15th Dakar Biennale. Photo: Haja Fanta.

Guest curators Kara Blackmore, Marynet J, and Cindy Olohou have addressed the ecological crisis with precision and depth in their exhibition On s’arrêtera quand la Terre rugira (We Will Stop When the Earth Roars). Bringing together evocative works such as Némo Camus’s sound installation Matter, exploring the impact of lithium mining in the DRC’s Manono, and Cléophée R. F. Moser’s video piece around the privatization of the Dakar coastline, the exhibition immerses viewers in questions about humanity's relationship with the planet.

Némo Camus, Matter, 2024. Installation view at 15th Dakar Biennale. Photo: Haja Fanta.

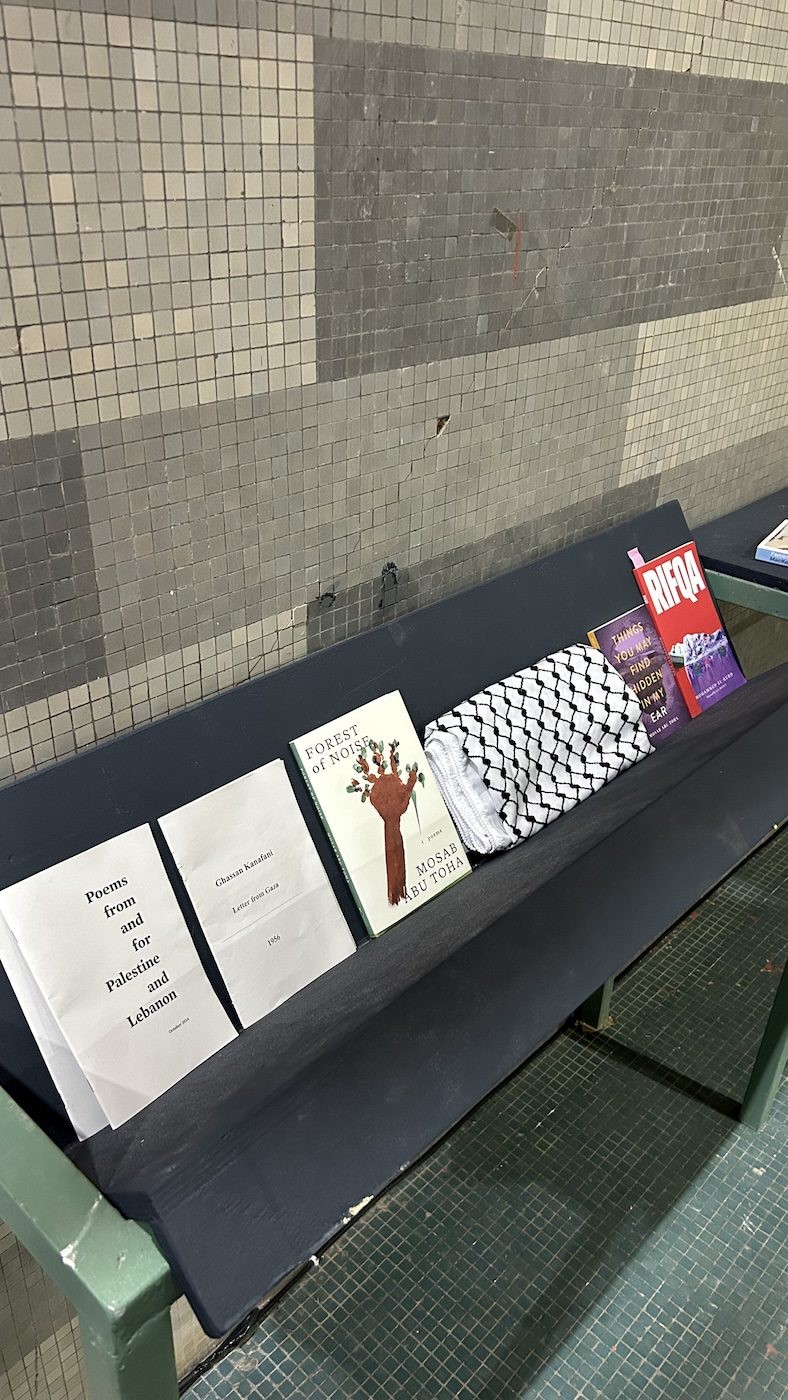

For navigation, the main exhibition is divided into sections: a tribute to Anta Germaine Gaye, a collectors’ exhibition, a curators’ exhibition, an international exhibition, and a design section. Also present is a “haptic library” presented by Archive Ensemble that reimagines the library as a souk – with books, music, and places of respite. Visitors are invited to touch and engage within the area, which includes offerings such as Ghassan Kanafani’s Letters from Gaza (1956). An extension of the Dak’Art program is situated at The Museum of Black Civilisations and the National Gallery.

Haptic Library by Archive Ensemble. Installation view at 15th Dakar Biennale. Photo: Haja Fanta.

Thematically, the biennial unfolds across four chapters: Swimming in the Wake, Dive into the Forest, Float in the Cloud, and Burn. At certain moments the curatorial approach veers into abstraction, lacking specificity – particularly in the international section. In her catalogue essay, Diop reflects: “I want to think about ‘wake’ as a problem of and for thought. I want to think about care in The Wake as a problem for thought and for Black non-being in the world.” These themes are broadly unpacked through explorations of migration, identity, colonial histories, and slavery. However, I found the connection between these expansive ideas and the exhibition’s individual works not always clearly articulated, and I grappled with locating the throughlines within the conceptual framework.

Majida Khattari, The Punishment of Roses, 2024. Installation view at 15th Dakar Biennale. Photo: Haja Fanta.

The space itself is orchestrated beautifully. If, like me, you stepped out of your taxi into the sweltering 31-degree heat, you would have rushed to seek refuge inside the former Palais de Justice. My dash for air conditioning was swiftly interrupted by an encounter with the work of Senegalese sculptor Ousmane Sow (1935–2016). A bronze sculpture from his Masaï series commanded attention, alongside the installation For Those Among Us Who Inherited Sacrifice: Rasanblaj! by Haitian American artist Gina Athena Ulysse, which cascades down the walls. Diop’s background as a composer is evident in the exhibition’s thoughtful pacing and harmony, with standout sections like the design exhibition, Wangechi Mutu’s A Palace in Pieces, Majida Khattari’s The Punishment of Roses, and the tribute to Anta Germaine Gaye leaving lasting impressions for me. Despite the delay and a certain abstraction, this year’s Dak'Art is a powerful platform for critical dialogue around art, ecology, and history.

Dak’Art – Biennale de l’Art Africain Contemporain running from November 7 to December 7, 2024, in Senegal’s capital.

Haja Fanta is a curator, researcher, and writer with a diverse and international practice, dividing her time between London and Dakar. Her research focuses on artistic and cultural production from West Africa and its diaspora, the relationship between art and society, and the role of the archive.

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission