Reflecting on oral tradition, rhizomes, and opacity, C& Magazine’s new editor-in-chief, Ethel-Ruth Tawe, shares 3 notebook entries and an invitation.

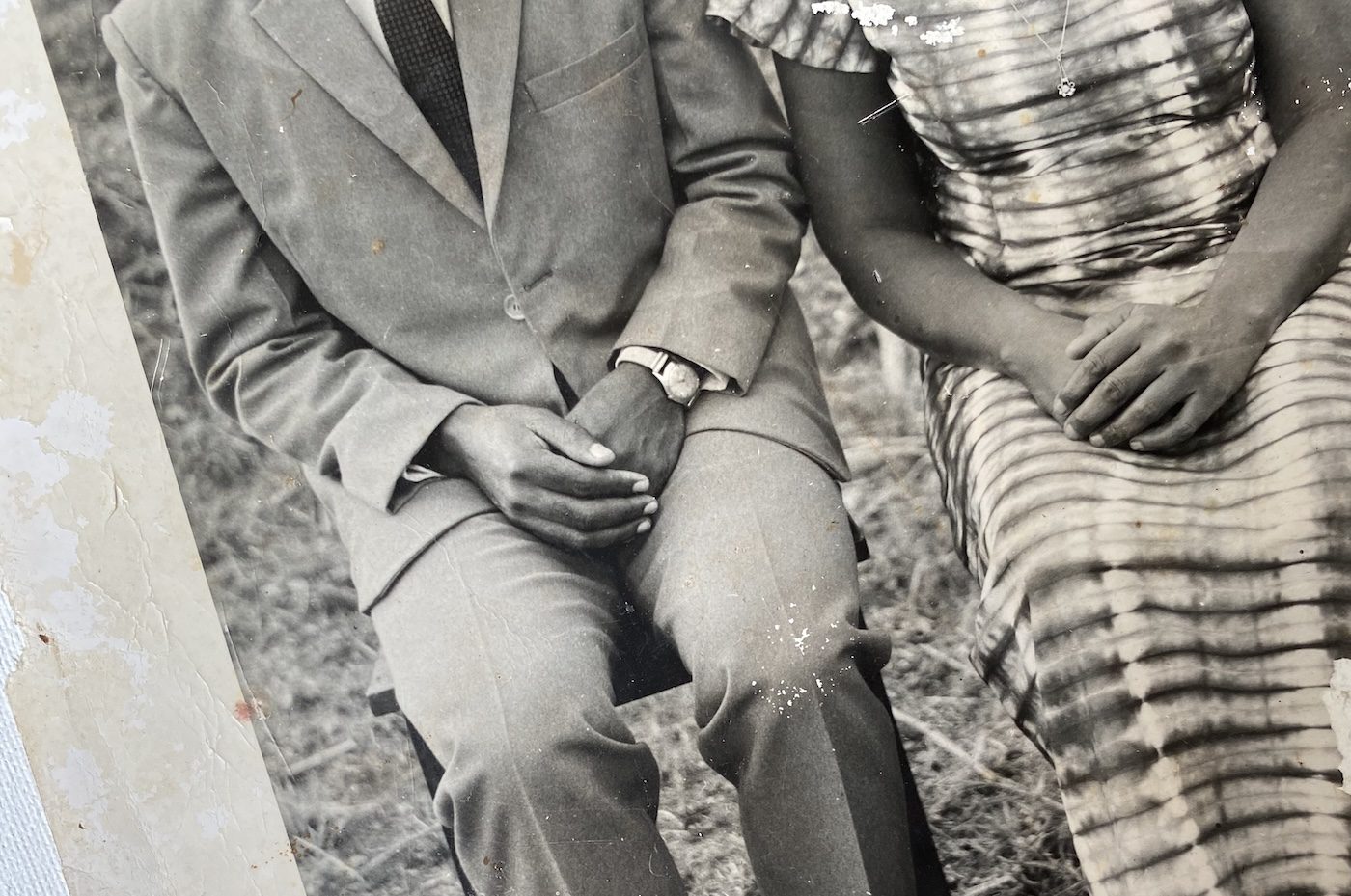

Family photograph, Ethel Tawe. Courtesy of the artist.

THE (MOVING) IMAGE

“Oral tradition is a tradition of images. What is said is stronger than what is written; the word addresses itself to the imagination, not the ear. Imagination creates the image and the image creates cinema, so we are in direct lineage as cinema’s parents.” — Djibril Diop Mambéty to N. Frank Ukadike in “The Hyena’s Last Laugh,” Transition 78 (1999)

I spent the past few years collecting and digitizing old photographs of my family, for what initially felt like no apparent reason. I would pull apart the adhesive on album pages bound together by time, passing the odd-sized sleeves through my scanner’s white light to timestamp yet another encounter with the life of a (moving) image. Most of the images had moved from Cameroon, to Tanzania and the Netherlands, while duplicates had been shared between family members, keeping their circulation alive, and moving us physically and emotionally. The back of the photographs revealed names of endearment, studio stamps, dates, and personal annotations, as though waiting to be found in the future. While the portraits allowed me to share eye contact with past loved ones, some whom I had never met, they also quickly opened up a lens into possibilities, led by embodied memory and intuition.

A RHIZOMATIC LINEAGE

“Knowledge has often strained at the seams of textual structures—seeking ways to slip the structure, move around in it, and make new connections or leaps. As newer networked technologies and phenomena like the internet have emerged, knowledge has found new ways to sprawl, connect, and network itself rhizomatically.” – Danah Henriksen and Punya Mishra, “We Have Always Been Rhizomatic” (2023)

We are always in conversation with several timelines. Time can be observed as a root system with people and cultures moving fluidly in unsystematic ways. Black feminist citational practices have guided many of us in mapping these roots, routes, chronologies, and counter-histories as threads that intersect at several nodes, especially in this digital age. It is the speculation and research of many artists, custodians, and thinkers, that continues to fill the epistemic gaps.

As we learn to dissolve hierarchies of knowledge production, whether linguistic, artistic, or embodied, what parts are being made most legible? What roots remain nurtured and buried beneath the ground and what annotations remain coded on the back of our photographs? I think of Edouard Glissant’s concept of opacity: the idea that some aspects of ourselves are unknowable and that this unknowability is a valuable part of human diversity. In fact, transparency through categorisation can be a tool of domination, forcings aspects of ourselves that are difficult to grasp, to fit into particular (often western) frameworks. It is possible to inherit knowledge from languages we don’t speak; opacity is an ancestral technology to some, and a potent apparatus of colonial discontinuum to others. A discontinuum of linear thought, embracing instead the patterns of rhizomes. Encoding and decoding is the work of artists and writers, a medium and process that creates records through a diversity of formats and access points.

UN/DEFINING ANTIDISCIPLINARY

“The very idea of a ‘living archive’ contradicts this fantasy of completeness. […] It cannot be complete because our present practice immediately adds to it, and our new interpretations inflect it differently.” — Stuart Hall, “Constituting an Archive” (2001)

It is somewhat paradoxical to attempt to define a principle that is boundless. The root word “fin” in “define” means “end or limit”; the inverse of what an antidisciplinary practice aims to do. For me, “antidisciplinary” resonated in a new way when I read an offering from UK-based heritage studio House of Dread, which led to my working definitions of the term:

1. Manifesting something new: worldbuilding and imagining beyond what already exists

2. Practicing refusal: working against the rigidity of disciplines and the tyranny of experts

The latter is borrowed from two sources: Practicing Refusal Collective’s “rejection of this current status quo as liveable,” further explained as “a refusal to accept Black precarity as inevitable, and a refusal to embrace the terms of diminished subjecthood through which Black subjects are presented.” The second source is William Easterly’s book The Tyranny of Experts (2014), about the technocratic illusion and “belief that poverty [and socio-economic development] is a purely technical problem amenable to such technical solutions.”

Many artists, writers, and practitioners who are not confined by one medium or invested in a linear path often struggle to explain what it is they do exactly. In a perpetual state of “and…”, they embrace and untangle many contradictions by constructing and deconstructing how we perceive our world. My shift to “antidisciplinary” came from an understanding of archival practice as abandoning the fantasy of completeness and embracing a shape-shifting process. Inheriting photographs, working in iterations, and re-writing the codes. An antidisciplinary practice defies traditional categorization and is rooted in experimentation and experience as an artform. It is always a work in progress, questioning the binaries of our current configuration and programming.

AN INVITATION

“Write to the work.” — Tina Campt

The family photographs I collected began to resurrect when I started layering them with sound and touch; my physical encounter with them. They became catalysts for imagining and living otherwise. Images and words are full of possibilities – the possibilities of life itself. Oral tradition has always been fluid, citational, and non-linear. As C& opens new chapters and turns a new leaf, we look to welcome more of a spirit of experimentation. In a lecture on The Opacity of Grief, Tina Campt encourages writing to the work as opposed to about it. To read the traces left against the grain of a photograph, or to prompt dialogue by how we position ourselves in relation to the work. This year, the C& team seeks pitches and texts that embrace contradictions, intersectionality, and antidisciplinary approaches, further expanding on serving our Francophone community. We are interested in formats that pull from a range of timelines and perspectives, spanning the aesthetic, the lyrical, and more; from conversations with elders to notes on material culture, cinema, new media, and gathering places, especially in times of crisis but also beyond. We are encouraging discourse that situates works and our lives in wider social or political contexts. Discourse that builds upon legacies, lineages, and citations that spiral backward and forward.

Ethel-Ruth Tawe (b. Yaoundé, Cameroon) is an antidisciplinary artist and creative researcher exploring memory in Africa and its Diaspora. She is editor-in-chief at Contemporary And (C&) Magazine. Image-making, storytelling, and time-travelling compose the framework of her inquiry. From photography, collage, and text to moving image, installation and other time-based media, Ethel examines culture and technology often from a speculative lens.

FEMALE PIONEERS

C&’s second book "All that it holds. Tout ce qu’elle renferme. Tudo o que ela abarca. Todo lo que ella alberga." is a curated selection of texts representing a plurality of voices on contemporary art from Africa and the global diaspora.

More Editorial