Showing Solidarity Beyond Borders

30 March 2020

Magazine C& Magazine

Words Aïcha Diallo

8 min read

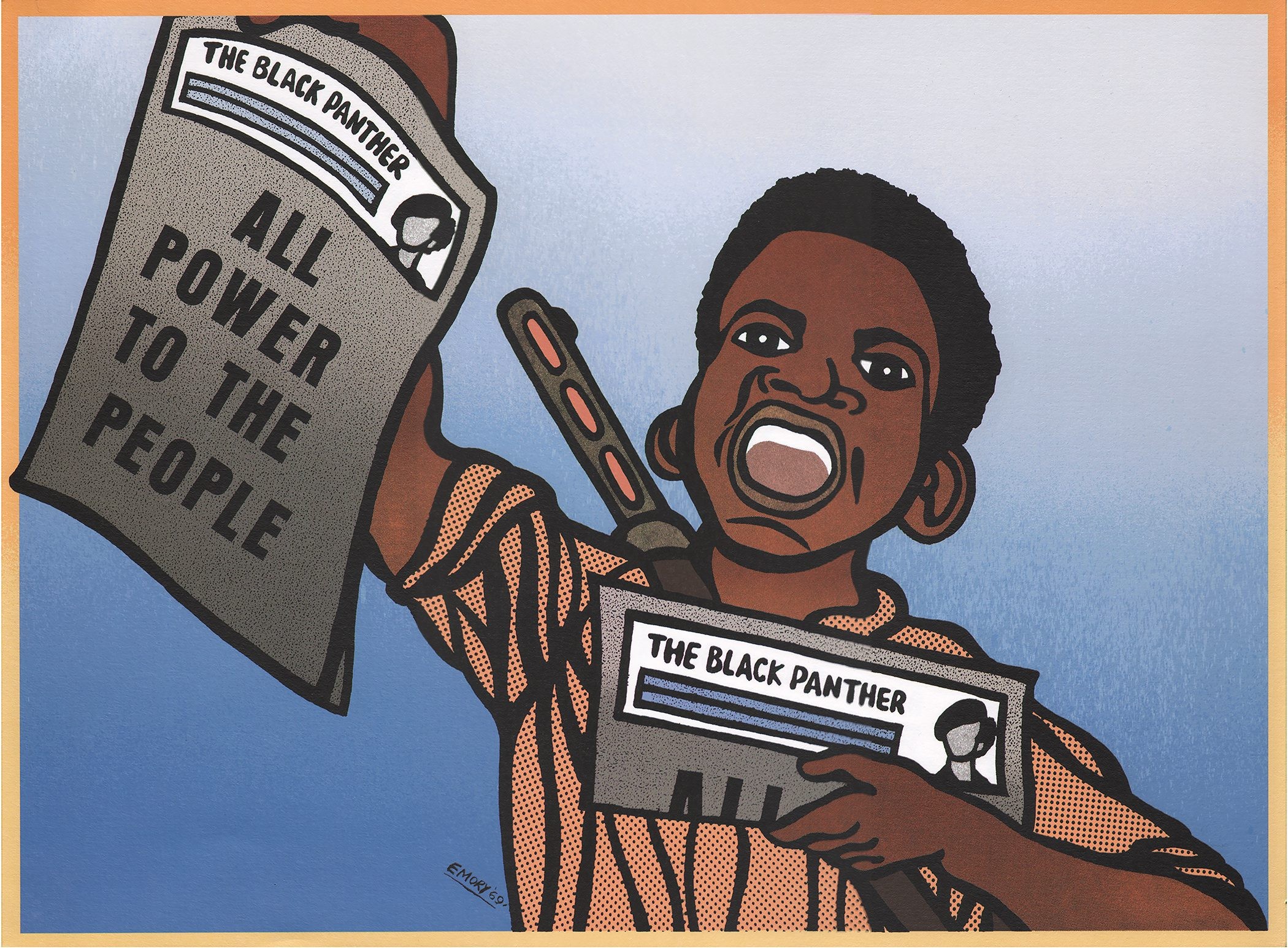

Mobility in the arts, geographical or otherwise, is often seen as almost a requirement. However, COVID-19 has put to the test this very idea and aspiration. In the series "States of Mobility" we have selected texts that probe assumptions of movement in relation to people on the African continent and beyond. Here Emory Douglas, former Minister of Culture of the Black Panther Party and art director of the Black Panther newspaper, talks to C& about art, activism and collective self-determination.

Referring to the title of an exhibition at the NGBK in Berlin, “Laboratorium der Solidarität” we run this series, focusing on solidarity movements. Because at this very moment we are experiencing an entire global movement calling for solidarity. In a time of uncertainty, people all over the world are prepared to act jointly. People are in solidarity against the Trump government. Against populism. Against racism. In solidarity for the preservation of the environment. In solidarity in the aftermath of terrorist attacks all over the world. This has inspired us at C& to take a closer look at important historic as well as present moments of people getting together to form solidarity movements, to fight for justice.

I joined the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (“Self-Defense” was later dropped from the organization’s name) in late January 1967, about three months after it had been founded by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale in October 1966 in Oakland, California. I was 23 years of age, and, like a lot of Black youth in the US at the time, we were very concerned with the police murders of Black youth all over the country that were constantly being justified. There were many rebellions that took place because of these unjustified killings by the police.

The Black Panther Party was formed as an organization to bring attention to the lack of basic quality of life, concerns and needs in Black communities across the USA. They had a Ten-Point Platform and Program, which encompassed the basic guiding principles of the organization, starting with point 1. “We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black community.” However, point 7. “We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people” was the primary point the party began practicing as it related directly to the party’s resistance against police brutality and murders, the primary reason why I wanted to join the organization.

My involvement with the party began when I was asked by some activist friends of mine to come to a community planning meeting. They were part of an initiative seeking to bring Sister Betty Shabazz, the widow of Brother Malcolm X, to town to honor her and they wanted me to do the announcement poster for the event, which I agreed to do. At the first meeting I attended, everyone was informed that some brothers would be coming to the next meeting and that they might take care of the security for the event. Eventually these brothers agreed to do so and it turned out to they were Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, the two cofounders of the Black Panther Party. After the meeting was over, I spoke with both Huey and Bobby about how I could become a member of the Black Panther Party and they gave me their phone numbers. Soon thereafter I would catch the bus to Huey Newton’s house in the morning and hang out with him. He would take me around the community, introducing me to folks. Afterwards we would go by Bobby Seale’s house. This was the beginning of my transitioning from the Black Arts Movement to the Black Panther Party.

The Black Arts Movement had a nationwide broad base and was primarily a Black cultural movement that focused on Black pride, Black identity, Black history, with many different outlooks on Black identity related to class. The Black Panther Party on the other hand was an organization. When I first got involved with the Black Arts Movement in the mid-1960’s it was as a graphic artist designing event posters and announcement handouts for community theatre. During that time in 1966 I was still enrolled at the City College of San Francisco (CCSF), taking a few graphic art related classes. While at CCSF, I became aware of the Black Student Union at San Francisco State University (SFSU), which I recall was either the first or second BSU in the country. Once I became aware of all the Black political and cultural activities that were happening I would go out to SFSU quite often. SFSU was where I met playwright Amiri Baraka aka LeRoi Jones at that time. He was invited by the SFSU Black Student Union to do community theatre outreach such as theatrical plays and poetry readings. It was soon after meeting Baraka that I began designing simple backdrops for his theatrical performances as well as doing more art work relating to cultural identity in the context of that time when we began defining ourselves as “Black” or “African Americans” and no longer as “Negroes”.

About four or five months later was when I joined the Black Panther Party and began doing prepress production work and graphic design artwork for our newspaper titled The Black Panther Community News Service – as the Revolutionary Artist and later as the Minister of Culture. Huey Newton said the paper was to tell our story from our perspective, it could be like a double-edged sword, praising you on the one hand and criticizing you on the other hand, apart from being a very powerful tool to inform the masses. The paper was meant to enlighten, inform, and educate people about local, national, and international issues. In the early phase of doing the prepress work on the newspaper we didn’t have any typesetting or computer equipment. All of our graphic layout production work was basically created by cutting and pasting the information in place – both for the newspaper and for the other graphic-related work. We had friends and allies in the printing business who had the technology and were able to print our newspaper and other graphic-related materials. Later we had our own in-house printing operation where we could publish everything we needed to except for our newspaper, which we continued to have printed elsewhere. We shipped our newspaper to all the 49 chapters and branches of the organization.

My artwork that appeared in the Black Panther Party newspaper was always a reflection of the philosophical and ideological perspectives of the Black Panther Party on current events worldwide. It was our political organ that enabled us to define our positions on issues. At its peak the circulation reached over 100,000 newspapers weekly, with an estimated readership of around 400,000.

Emory Douglas. Photo by Jos Wheeler

Fast forwarding to today, I would define myself as a conscious person doing socio-political artwork, as an elder in the movement for social justice committed to doing art collaborations with other artist and art-supportive organizations. I’ve had the good fortune of collaborating and exhibiting in different places in the world. To name a few, I was invited by EDLO Art Space in Chiapas to collaborate on a collective art project titled Zapantera Negra; I traveled to Australia, where I collaborated with an aboriginal artist; in New Zealand I worked with a Maori artist. I have been to Portugal, Lebanon, Colombia, and Cuba, where I exhibited in the Havana Poster Festival in April 2016. Prior to that I was part of a delegation that traveled to Palestine for twelve days. There’s been lots of interest in retrospectives of artworks from the 1960s and 70s which I did as a member of the Black Panther Party and I do a lot of lecture presentations about the history behind that period of my artwork.

A few months ago I went to Tanzania, where the former Panthers, Sister Charlotte and Brother Pete O’Neal, have been living since the 1960s. Sister Charlotte travels back and forth to the US several times a year. They founded a youth and community organization called the United African Alliance Community Center (UAACC) in the village of Imbaseni, located near the northern Tanzanian city of Arusha. They continue some of the same kind of community programs we implemented back in the 1960s and 70s with the Black Panther Party.

My main intention with my art-related travels has always been to show some solidarity beyond borders with different people’s struggles for a better quality of life. For me it’s not about going there to tell them anything but to learn, to be informed, and to share as well as to see the commonalities in our struggles. After all, the reality is there’s extreme exploitation happening everywhere. You have indigenous people and aboriginal people who are by far the most impacted by unemployment, incarceration, health issues, a lack of quality education, gentrification, exploitation of their land for natural resources – these are all commonalities that transcend borders. What informs me today when I travel to different places is the continued struggle for self-determination.

I think sometimes that is why the content of the artwork I’ve done and continue to create in many ways resonates with people beyond borders. What people can see through the artwork are some of the same basic human rights issues and they realize in their collective realities these must be resisted.

Aïcha Diallo is an Educationist, Cultural Analyst, Editor and Writer from Berlin.

Read more from

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Irmandade Vilanismo: Bringing Poetry of the Periphery into the Bienal

Esperanza de León: Curating Through Community Knowledge

Read more from

Prince Claus Impact Award Presented to Six Artists from Diverse Disciplines

Marielle Franco: five years on, what has changed?