Re-enacting the Past

. What could lead a group of curators or an institution to set up an exhibition dealing with art produced in a period already as intensely explored as the postwar? Would it be possible for a German institution to propose another perspective on artistic production of that period? “Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and …

.

What could lead a group of curators or an institution to set up an exhibition dealing with art produced in a period already as intensely explored as the postwar? Would it be possible for a German institution to propose another perspective on artistic production of that period?

“Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945-1965”, which opened in October 2016 at the Haus der Kunst (HDK) in Munich, seems to answer the above questions by presenting around 350 works produced on different platforms and mediums, as well as documentary material recording social and cultural movements over the 20 years it addresses. Curated by Katy Siegel, Okwui Enwezor and Ulrich Wilmes, the exhibition is the result of nearly eight years of work - conferences, intensive research and countless meetings and exchanges between curators and researchers from other institutions in different regions of the world. The curators assert that the show shall be more focused on the importance of proposing another reading of this historical moment - something beyond the aftermath. Firstly it shall spotlight the eight chapters or themes of the exhibition, which contribute to the introduction of other narratives and artists who for a very short time were related in the years following the end of the Second World War.

.

<figcaption> Ben Enwonwu, Going, 1961. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of

University of Lagos

.

In this manner, it is impossible not to associate it with the current attempts of historical reviews that several European cultural institutions undertake. Perhaps because of the pressures of social movements - or a mixture not yet defined between acknowledgment of guilt and the will to once again take center stage in the narration of history - re-readings of the past have been expensive themes for some of these institutions. These include the controversial exhibition on German colonialism at the Deutsche Historisches Museum or even the construction of the controversial Humboldt Forum, both in Berlin. The show may share some of this feeling; however, it bears an important difference -the presence of Okwui Enwezor. The artistic director of HDK is one of its creators and has a notorious and pioneering trajectory of inserting artistic productions from beyond the West.

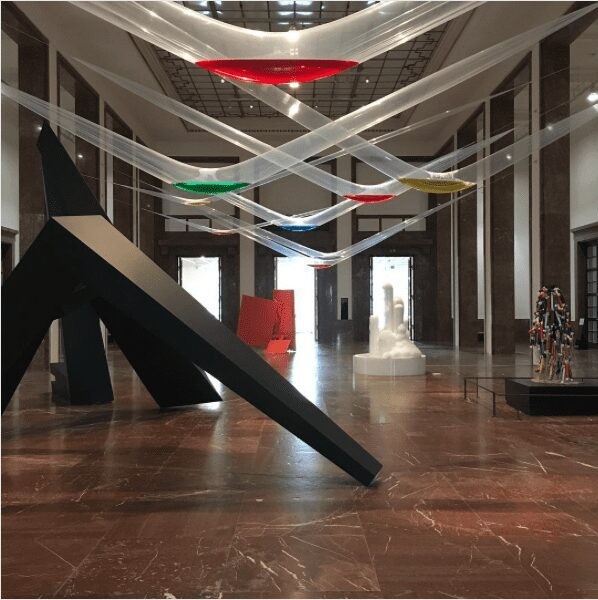

Upon arriving at HDK, the doubt and a certain skepticism that I still felt about the project, were mixed with the strange sensation of visiting for the first time. The neo-classical building definitely does not resemble anything else around. All that physical structure and the still-visible Nazi remnants make it impossible not to reflect on its difficult past. Its magnitude functions as a space of reflection that certainly guided my gaze in the two days I visited “Postwar”. This same magnitude offers an interesting space for the installation “Work (Water)” 1956, the emblematic work by Sadamasa Motonaga, produced with vinyl sheets filled with dyed water and presented for the first time in a park in Japan between nets and trees; or even when you look at Atsuko Tanaka’s wearable sculpture “Electric dress”.

The choice of works such as these herald the direction the curators seek. In the exhibition catalog Katy Siegle stresses her attempt to understand these 20 years in a global sense. And that means not only adding new names to the canon, but rather "searching for artists to help us rethink categorizations of art and the criteria we often use for its appreciation and understanding." There are conflicts and contradictions everywhere, but “Postwar” actually offers a thorough presentation on the artistic production of the period, beyond what permeates our imaginary.

Chapters 2, 3 and 7 seem to me to be the ones that best carry out this mission, with success or conflict. In Form matters (chapter 2), Pollock is present with “There were Seven in Eight (1945)” and “Number 23” (1948), but we also see Anwar Jalal Schemza’s “City wall” (1960) and “Composition in Three Parts” (1963/1964), and Princess Fahrelmissa Zeid’s “My Hell” (1951). The works of Atsuko Tanaka and Sadamasa Motonaga mentioned above, as well as other records on Gutai, are part of the chapter, which brings other good surprises such as “B17, Glass Bólide 05 ‘Homenage to Mondrian’” (1965), by Helio Oiticica, and Lee Seung-taek’s “Non Sculpture” (1960). As the title suggests and the wall text guides, the theme focuses on issues and formal elements, presenting abstract-conceptual works, produced in the US and Europe, in relation to artists who would have, either for local or material reasons produced its own responses to the then new Western experiments. The presence of non-Western artists in a way that seeks connections and affinities between different visual cultures, does justice to the discourse of the exhibition. However, the idea that non-European/non-American productions would be responses to Western innovations is quite paradoxical, and reinstates the centrality the period’s production back to the Europe and the United States.

Chapter 3, New images of the man, follows the same premise by juxtaposing artists from different geographic and ethnic backgrounds. Here they present those who have worked with both figurative representation and with abstraction simultaneously, or as curators point out: fleeing or refusing to have to choose one or the other, in search of possible representation of this new "man." And who would that subject be? We see Ibrahim El Salahi’s “Funeral and the Crescent” (1963) between “Massacre in Korea” (1961), part of Picasso's anti-war trilogy and On Kawara's “Thinking Man” (1952). Maqbool Fida Hausain’s “Man”, (1951) stands close to “The Cage - first version -” (1949/50) and “The Clearing” (1950), both by Alberto Giacometti which are in a possible dialogue with Ben Enonwu’s Anyawu (1954-55).

.

<figcaption> Installation view Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945-1965, 2017. Instagram photo by Adriano Pedrosa

.

There is something interesting to note in chapter 7 (Nations seeking form). And that is “Birmingham” (1964) by Jack Whitten, a resounding critical work of police violence against black American protesters during the Civil Rights Movement period as well as “Tabaski-Sacrifice of the sheep” (1963), a series of canvases by Iba N’diaye or even Ben Enwonwu’s “Going” (1961). Once again we find elements that guide the exhibition, the inclusion of either Iba N'diaye or Ben Enwonwu in this chapter is not unexpected (despite the surprise they could cause when we think of what was hitherto established as postwar art), since the work of both is strongly linked to the construction of national-artistic identities of their newly independent countries. But putting them together, in dialogue, with the work of Jack Whitten, enables us to deal with Whitten's work not only as part of a minority's narrative of struggles within a nation, in this case the US, but in a transnational context.

Re-enacting the past in an interrelational reading of the world, “Postwar” evokes paradoxical feelings by posing questions and making us look critically at history. As a good friend said, it might be more interesting if the exhibition was a permanent one with eventual exchanges and insertions of works.

As much as there is an effort to seek other perspectives to see the world, there is a strong recentralization of the narrative, basically by the very idea, by the initial argument of postwar exposure, as some sort of ground zero. The choice of postwar itself is problematic, but it can act as a lens that accentuates the forces of contradiction when an European institution puts such a project forward. Yet still, it's all a question of power and “Postwar”'s contribution and the barriers it pushes break ground, especially for having Okwui Enwezor as one of its creators. Enwezor is now part of the establishment as well as what “Postwar” proposes. But visiting the show opens conditions and possibilities for rethinking and reorganizing rules and categories; maybe even destroy them.

On my second visit, shortly after leaving the galleries, I saw Okwui Enwezor in the shop. We didn’t know each other, but I had many questions. I approached him in the attempt to at least ask him one thing but I couldn’t. I should have at least returned the question he posed towards the end of “Postwar”'s inaugural conference: “How do we rethink the rules of the game?”

.

.

Thiago de Paula Souza lives in São Paulo, where he works as an educator at the Afro-Brazilian Museum (Museu Afro Brazil). His current research concerns race relations, African and Afro-Brazilian art, and the depiction of art from Africa and the diaspora in the German-speaking context.

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission