On How to Protect Women’s Stories

A digital museum wants to preserve Zambian culture from a female perspective and make it accessible for a broader audience.

In 2021, Hannah Siliya worked with a community of artists on a unique project. The twenty-three-year-old Zambian was selected for the Fabricated Stories residency programme, an initiative of the Women’s Museum of Zambia, to create Zambian art objects based on those currently housed by the Swedish Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm.

European museums have artefacts from all African countries – Zambia is no exception. The Fabricated Stories project was part of a broader discussion around art reparations; in this instance, digital art reparations are a temporary solution before actual physical reparations.

“As a graphic designer I’m drawn to patterns and color,” Siliya says. “I decided to recreate the Zambian monetary system using the patterns and symbols from the artefacts I saw, and so my collection became one about money.”

As indicated by its name, the Zambian Women’s History Museum was created in 2016 to preserve and celebrate a particular part of Zambian culture: its focus is on making Zambian women’s histories available and accessible to the public.

The museum swiftly partnered with Wikipedia to train thirty-four young Zambian writers how to write entries documenting the stories of Zambian women for the website. But this presented its own challenges.

“Our oral traditions are how we’ve kept our history consistent and constant – in poetry, praise names, village names. We have real reference points that Wikipedia doesn’t recognize,” says Mulenga Kapwepwe, co-founder of the museum. “When you write about an African woman who’s never been written about, Wikipedia just says she’s not important and ignores her.”

Women’s Museum co-founders Mulenga Kapwepwe (sitting) and Samba Yonga (right), joined by Choma Museum curator Victoria Phiri (left)

Kapwepwe and her team are finding solutions to this apparent clash between African and western forms of provenance. They have created a women’s research and publishing collective that will publish articles about these histories in academic journals, which will in turn provide the references needed by the likes of Wikipedia.

In recent months the Women’s Museum has been holding active discussions with the Swedish Ethnographic Museum and is watching with interest the process of the Czech Republic returning artefacts to their original communities in western Zambia. As Kapwepwe and her team are finding, the process of repatriation is rarely straightforward.

“There are so many laws that get in the way of us getting our objects back from the European museums,” she observes. “One of the things we’re noticing is that it’s the western museums that decide which objects are sent back.”

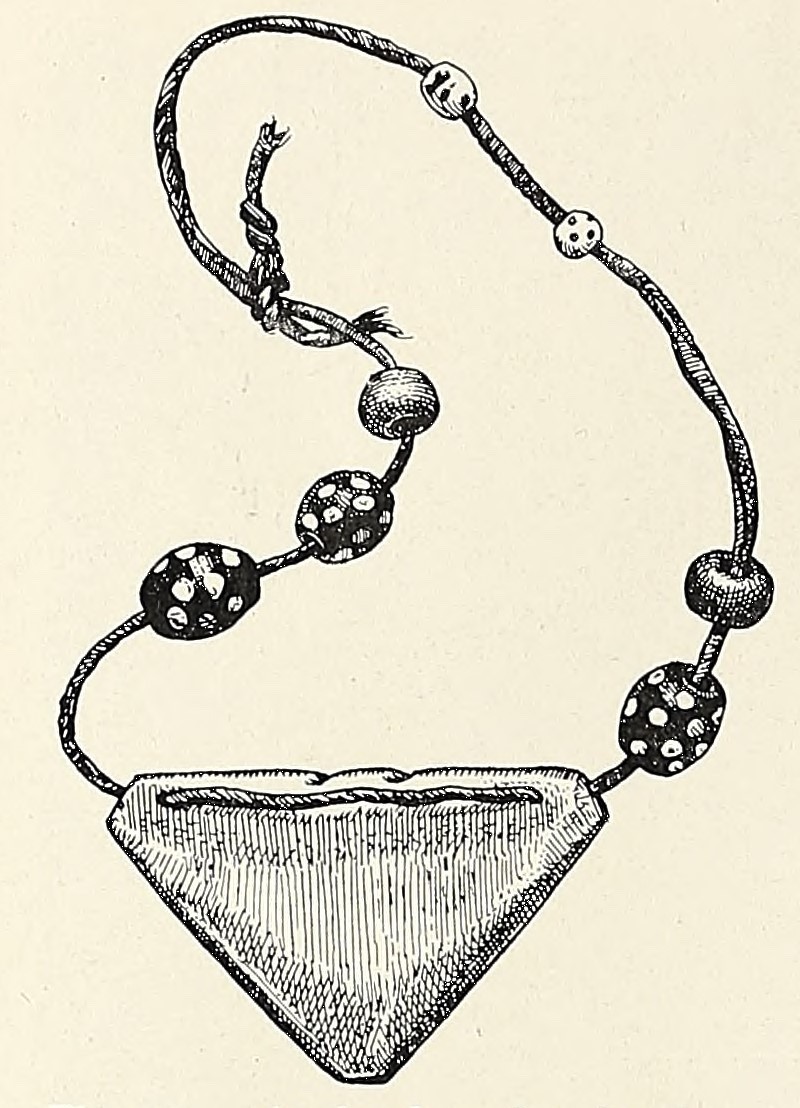

Bracelet with ivory jewel from the Ushi people, Zambia

Acknowledging that if objects are returned to Zambia a certain institutional capacity to ensure they are preserved well will be required, the museum invited experts from the Swedish Museum of Ethnography, which holds about 800 artefacts taken from Zambia, to come and assess that capacity.

The evaluation suggested that Zambia has the capacity to look after the paper and photographic artefacts, but needed to invest in infrastructure for other items. “As long as we know the path that we need to take, which means investing in infrastructure, we know what to do,” Kapwepwe says.

A major part of their plan includes constructing a physical space for the artefacts. Kapwepwe and her team were recently gifted some land on the Chaminuka Private Nature Reserve in Lusaka for that express purpose. For now, however, they are trying to derive maximum benefit from being solely digital.

“We very strongly think that the digital age is Africa’s age, and we need to take advantage of that,” she says. “To give Africans access to their objects, as a first step you can do it digitally.”

Collaborative discussions between Swedish and Zambian teams in Lusaka

In that spirit, the team started a podcast series in 2019 called Leading Ladies. It documents the lives of notable women going as far back as the seventeenth century. Popular episodes include stories about religious leader Alice Lenshina Mulenga, beauty queen Christine Munkombwe, and conservationist Thandiwe Mweetwa. The latest series, on eco-feminism, showed how Zambian women have fought for environmental justice over the years.

Kapwepwe’s passion for the preservation and celebration of culture comes directly from her upbringing. Her parents, Simon and Salome Kapwepwe, were part of the independence struggle and emerged as important leaders during that period. After independence in 1964, her father served in various government roles including as vice president.

“Growing up, a love for culture was deemed extremely important in our home. I think it filtered through my mother’s milk!” she laughs. Although she didn’t study history at school, “there was always a sense of history happening in our house,” which has since inspired her work with local museums, playwriting, and community cultural organizations.

Art exhibition at Chena Art Gallery, Nkwashi, Lusaka

The journey of the museum has taken some unexpected turns. Its novel approach to cultural preservation has been noted by others outside Zambia. “We were asked to help the Sami people of Finland curate their museum, to express their experience,” Kapwepwe says. They were also invited to join the African Museums & Heritage Restitution advisory council, and their systems of provenance grabbed the attention of Yale University.

Kapwepwe is determined to harness technology and shake up the museum space. “We see ourselves as pathfinders and flamethrowers,” she says. “The museum space is stuck and there’s so much it could be taking advantage of.”

For younger Zambians like Siliya, the Women’s Museum is filling a new generation with pride in their cultural heritage: “The Fabricated Stories project was really dear to me,” Siliya says. “For the first time, I was able to create from a place of understanding. It came out of me flawlessly. It was a space that enabled me to grow and identify with stories that represent people like me.”

Chipo Muwowo is a UK-based Zambian freelance journalist. He writes about the arts, business, and investment in African markets.

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025