N’Goné Fall: More than a Season

12 May 2021

Magazine C&

9 min read

Julia Grosse: Although you’ve made it clear many times that Africa2020 is not a cultural season, it is still an “African season.” Can you tell us about your concept for this huge project? And why it is a French event? N’Goné Fall: Well, it takes place in France because it’s an initiative of the French president. …

Julia Grosse:</strong> Although you’ve made it clear many times that Africa2020 is not a cultural season, it is still an “African season.” Can you tell us about your concept for this huge project? And why it is a French event?

N’Goné Fall: Well, it takes place in France because it’s an initiative of the French president. His desire was to have a personality from the African continent lead the project. So that’s how I was contacted, and then I had several discussions with members of his cabinet in March/April 2018.

France organizes a cultural season every year. But it usually focuses on one country, which makes it largely a bilateral diplomatic and political agreement. In our case, African states are absolutely not involved – it isn’t a diplomatic project.

From the very beginning it was clear to me that we needed to go beyond the idea of culture to avoid the temptation of doing a huge spectacle in which we’d disseminate artistic production with happy Africans in boubous and djellabas, singing and dancing.

The Africa2020 Season is built around twenty-three major twenty-first-century challenges. I started working on the project by initiating a week-long brainstorming workshop in the north of Senegal with four African personalities (Ntone Edjabe, Nontobeko Ntombela, Folakunle Oshun, and Sarah Rifky). The goal was to identify common issues that are generating research and production, whether scientific, artistic, or intellectual, on the scale of a continent. I keep reminding the French that neither I, nor my colleagues, agreed to be involved in this project to entertain anyone. While we do feature music and art, we first and foremost talk about the challenges that contemporary societies are tackling – about the past, the present, and mainly the future.

Yvette Mutumba:You said that the participating countries are not involved in a diplomatic way. Did you still get some reaction or feedback from official representatives?

NF: Africa2020 is not about country representation. It is a pan-African project involving the changemakers of the continent's civil society. It was the decision of the French president not to involve the political side from the continent, and that is fine for me. But as the project is happening in France, where most of these countries have embassies, I wanted to present my concept to them – as a matter of courtesy. So we organized a meeting at the French Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs and invited all the embassies. I had exchanges with the ambassadors to South Africa, Gabon, and Nigeria, because they wanted to know what was happening and if they could be of any help. I sent a message to the embassy of Senegal, my embassy, asking them to just support me morally, which they understood.

YM: We know that it is very complicated to work with institutions from all over France. But do you get the feeling that there is a chance for larger structural change?

NF: That was the strategy. You don’t change behaviors or mentalities by just doing music concerts. And it was crucial to avoid French institutions submitting an “African project.” The subtitle of the Africa2020 season is “An invitation to look at and understand the world from an African perspective.” It is about how Africans address issues related to the state of contemporary societies. Designing a project with African organizations or personalities was mandatory. France’s main cultural, educational, scientific, and economic networks on the continent are in West Africa, in the French-speaking countries. My role was to give the institutions access to networks that they don’t yet know, out of the Francophonie, in order to involve diverse African voices, regardless of the language they speak.

The goal was also to create long-term projects, beyond the time frame of the Africa2020 season. For instance, the theater Le Grand T in Nantes, the festival Les Récréatrales in Burkina Faso, and the Kenani Theater Festival from Mozambique have decided to sign a three-year partnership. Other organizations are planning similar long-term collaborations.

I was able to convince the French Ministry of National Education, Youth and Sport to be a strategic partner, so schools are doing about 275 projects. Each school found a partner school in a city on the continent. They are designing pedagogical tools together and are doing online workshops. Those partnerships started during the school year in October 2020 and will run until June 2021. Some schools are even planning to continue this long-term.

Another project is related to UNESCO’s General History of Africa series (started in 1964) with a network of African historians and scientists. At the request of the Africa Union, in 2009 UNESCO transformed the eight volumes into pedagogical tools. The ambition is that in the midterm all children on the continent learn the history and geography of the continent using the same tools. These tools have been produced in French, so I decided to offer them to France. In October the French Ministry of National Education, Youth and Sport started implementing a program called “Teaching Africa,” for which UNESCO recommends specialists from the continent and the diaspora to train French teachers. My strategy has been to use the Africa2020 season as an anchor to make these kinds of pilot projects possible.

We have also produced two publications on visual arts and history for kindergarten and primary schools. Across the French mainland and overseas territories, 1,200,000 copies have been sent to school kids. That’s part of my vision to have projects and programs with a strong long-term impact on young people.

[cand-gallery image-no=1]

JG:Africa2020 will cover the whole of France over several months, involving over 80 cities, fifteen headquarters, 450 projects, and 200 events. How did COVID-19 impact the concept?

NF: The first impact was postponement. Because the first lockdown started mid-March and Africa2020 was to launch June 1, we realized there was no way to open. We had to find new dates and that meant contacting all 180 partners in France and 200 on the continent. So that was a nightmare. We decided to open December 1, and then the second lockdown arrived late October.

The second lockdown was to be lifted on December 15. We were planning to have an official launch with In Quest of Freedom, carte blanche to El Anatsui, a site-specific installation El Anatsui created at Conciergerie, a heritage monument in Paris. El Anatsui is a senior Ghanaian artist, an international mega-superstar who dedicated part of his life to education, as a professor at the University of Nsukka in Nigeria. So for me it made a lot of sense to open this season dedicated to young people with him. Bisi Silva was supposed to curate it, but unfortunately she has passed on, and El Anatsui said I should do it.

JG:The eruption of the Black Lives Matter movement also had an impact on the world last year. Will the season respond to young French people’s urge to understand what it means to be Black, of African descent, and French in France? Will the movement have an impact on Africa 2020?

NF: George Floyd and Black Lives Matter didn’t have a significant impact in France. Some people did demonstrate and ask for conversations, but then the French government said: “We are not taking down any statues. Period.” France sees it as an American issue. There has been no serious conversation at all and there seems to be no will so far to have one.

JG:Not yet?

NF: I think the Africa2020 season will have an impact on people who will see Black curators, Black scientists, Black academics, Black entrepreneurs, and Black festival directors, and realize that these people are professionals with international networks. For many in France it is kind of surprising to realize that people on the continent and in the Diaspora are connected 360° while their own networks are tiny French-speaking or, let’s say, Western European networks. Suddenly they have to recognize “the other” as equal, or maybe even as having more knowledge, skills, and experience than themselves.

JG:So no statues were pulled down or pushed into the water?

NF: The French officials don’t even want a conversation about the statues. That’s where it starts. I think that the African Diaspora in France has lost hope and energy because there are invisible walls all around them. I think many of them have just given up; they feel that nothing will ever change, and some of them are considering moving to Germany, the UK, or the US, or to return to the country of their parents or grandparents in Africa. Some of them feel that they have no future in France, their country, which is terrible.

There is also a difference between French Caribbean people and those who are second-generation Africans. It’s not the same history. Those with ties to the Caribbean have issues with slavery, those with parents from Africa have issues with colonization. It is not a single group that says “let’s fight together.” In the UK that’s what happened in the 1980s. But it’s not yet the case in France.

For me education is the key to making changes. That’s why a lot of my energy goes towards designing strategies, convincing ministries, schools, and universities to become partners and then move on with a project that can go beyond Africa2020. If people can learn and understand how their history is and has always been connected to the rest of the world, societies might be in a better condition.

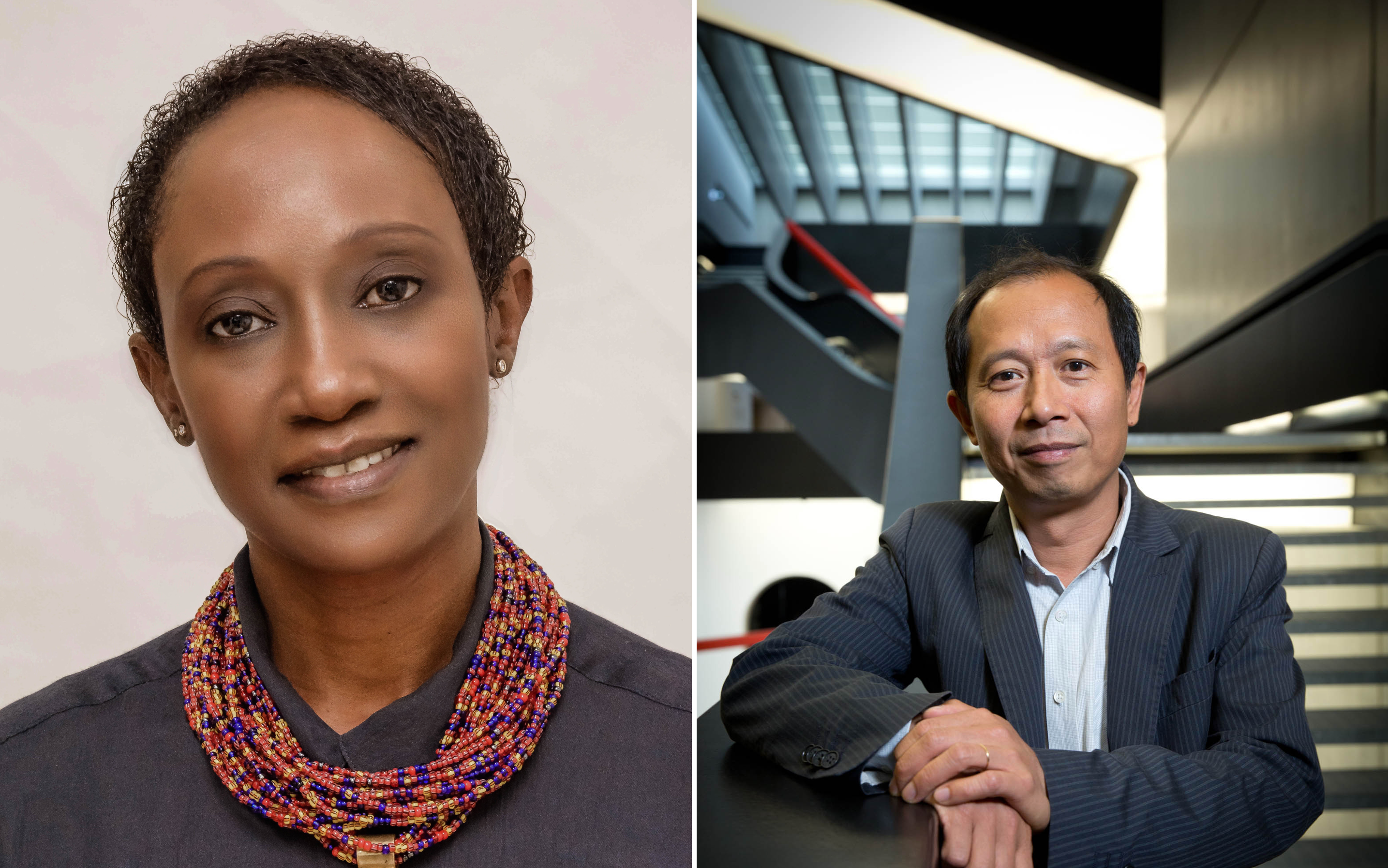

Independent curator, art critic and consultant in cultural engineering N’Goné Fall graduated from the École Spéciale d'Architecture in Paris. She has been the editorial director of the Paris-based contemporary African art magazine Revue Noire from 1994 to 2001. Fall is a co-founder of the Dakar-based collectiveGawLab, a research and production platform for art in the urban space and digital technologies applied to artistic creation. She has curated numerous exhibitions in Africa, Europe and the USA.

Julia Grosse and Yvette Mutumba are co-founders and Artistic Directors of Contemporary And.

Read more from

Contemporary art

MAM São Paulo announces Diane Lima as Curator of the 39th Panorama of Brazilian Art

Naomi Beckwith Unveils Core Artistic Team for documenta 16

Fundação Bienal de São Paulo Announces List of Participants for its 36th Edition

Read more from

N’Goné Fall

N’Goné Fall is Part of the Documenta Finding Committee

Dekoloniale Berlin and C& Announce Jury Presidents for Residency 2023