Meleko Mokgosi: “the limitations that produce narrow interests are not caused by the artist”

In our ongoing series of round-table discussions we ask a selection of artists and art practitioners to answer a set of questions on a specific topic. This time around the theme is “identity” and here C&'s deputy editor Will Furtado talked to Meleko Mokgosi.

“Identity” and “identity politics” are terms with which artists from Africa and the Diaspora are often associated, whether they like it or not. This has been the case for decades, or rather ever since there has been a debate around artistic production by artists from African perspectives. The idea that those artists are working on “identity” may be one of the assumptions made by a “Western” audience — and this applies just as much to Black communities. But is this fair? Is it not also leading to a “burden of representation,” as Kobena Mercer once called it? What does it really mean to make work on our “identity”? And who gets to decide that? And what about those artists with African perspectives who aren’t addressing the issue of “identity”? Their work and viewpoints are relevant and important, as they move away from this “burden to represent.” In this round-table discussion, four intergenerational artists discuss the problematics of these terms and their usage.

Meleko Mokgosi is a Botswana-born, New York-based artist who works within an interdisciplinary framework to create large-scale project-based installations. His approach to examining history, which primarily involves a critique of historiography through history painting, is centered on southern Africa as a case study. Currently he is working on Democratic Intuition (2014 – present), a project based on the idea that democracy is something that – according to Gayatri Spivak – is founded on the double bind between alterity (other) and ipseity (selfhood), in relation to the daily-lived experiences of the southern African subject.

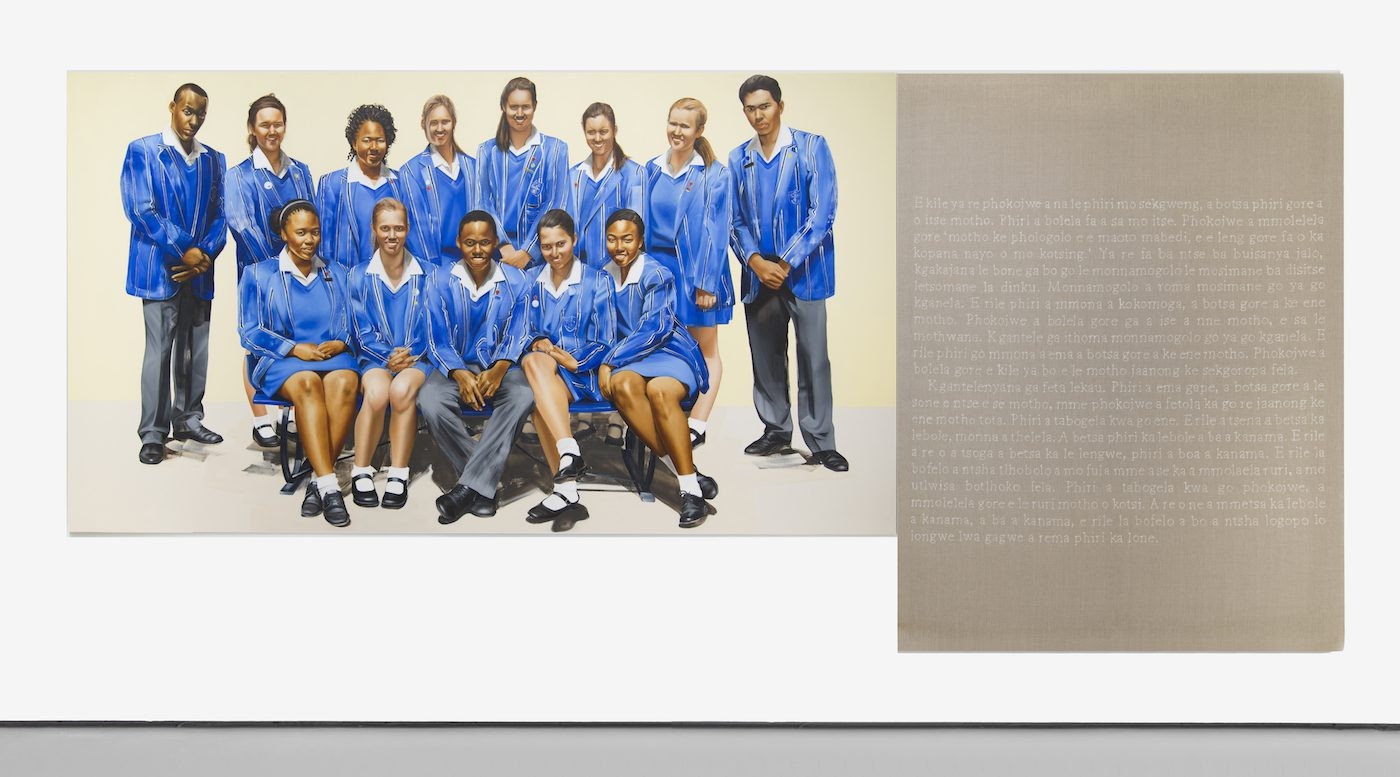

Meleko Mokgosi, Democratic Intuition Comrades VII, 2016 © Meleko Mokgosi. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Contemporary And (C&): In your paintings, you examine the role of history and how that translates to the present. With your main focus being Black subjects, what significance does this focus have for you and your work?

Meleko Mokgosi: My approach to examining history, which primarily involves a critique of historiography through history painting, centers on southern Africa as a case study. I am reluctant to say that I focus on Black subjects because this presumes a number of things that I am ambivalent about. Admitting to this would first and foremost propose that the paintings reflect a preoccupation with the notion of race, and the binary of White versus Black within this discursive framework. Although, as an African, I am aware of the histories and politics of race and how these are implicated in the colonial legacies of the region, my first priority is to articulate questions I am invested in, and simultaneously represent and voice experiences and histories that have been excluded from dominant narratives.

For example, my current, project Democratic Intuition (2014 – present), doesn’t begin with the Black subject but rather with the idea that democracy is something that is founded on the double bind between alterity and ipseity (to follow Gayatri Spivak’s phrasing), in relation to the daily-lived experiences of the southern African subject. Thus the project focuses on the ways in which democracy is something that is inscribed within the individual by various institutions, and how access to knowledge on how to use the state and its apparatuses affect a subject’s claim to democracy. These ideas, I believe, examine larger systemic and historical issues that include but are not limited to questions of race.

Secondly, the specificities of the images, compositions, and histories that my paintings engage with actively try to stay away from overt encounters with race discourse. The primary reason for this, which is more strategic than anything else, is that the continued fascination with race and Blackness in the fine arts and beyond has produced a peculiar effect, namely that the image of the Black subject within any narrative trope is always overcome by the politics of Blackness. It seems virtually impossible for the Black subject in any narrative to exist as just a subject, without a viewer projecting histories, metaphors, and metonyms connected to Blackness. These limitations obscure important specificities about the lived experiences of any given Black subject, and perpetuate the binaries and politics through which Blackness is produced and situated. So my strategies of engaging with the Black subject (and here I should acknowledge that I am referring to Blackness in the African context and not to African Americans) is important to me because it is a way of figuring out the extent to which it is possible to delay projecting essentializing history, metaphors, and metonyms onto representation of the Black subject, therefore allowing for an alternative abstraction of the subject within any given narrative.

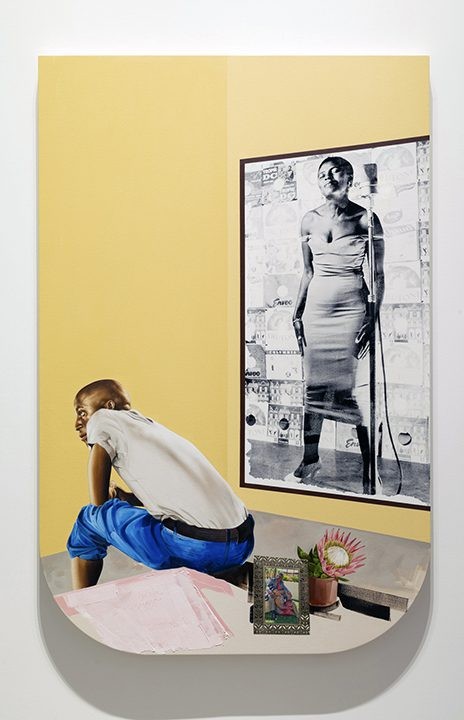

Meleko Mokgosi, Acts of Resistance. Exhibition view at The Baltimore Museum of Art, 2018. Courtesy the artist and The Baltimore Musuem of Art.

C&: Why do you think “identity” (in the broad sense of the word) is a recurring topic with artists from Africa and the Diaspora across generations?

MM: I don’t think it is something that is necessarily recurring but is always there. It just so happens that the discourse and history are invested in pulling out and projecting identity materials onto certain artists and their work. But to address the question in more detail, I think what is conventionally called ‘identity’ is also tied to ‘identity politics’. So we have to first agree that identity is first and foremost the way in which a person conceptualizes who they think they are based on both internal and external points of reference; and that ‘identity politics’ is a way of acknowledging how all subjects are differentiated, in addition to respecting these differences as evidence of the limits of empathy and that there can never be perfect identification. From here we can then make the move in connecting these ideas to humanism and the formation and development of the fine arts as a discourse.

In many ways, the entry of different aesthetic objects, tastes, and histories into the dominant conventions actually affects the ways in which they are perceived and develop. African art, for example, entered the (Western) art historical canon first and foremost as essentialized anthropological objects made by anonymous people during an unspecified time period, and the opaque meaning of these objects rests on a specific cultural context and not beyond that. Therefore any appreciation of the aesthetic and formal qualities of these regionally specific and essentialized objects (mostly acquired through force) – this appreciation has to happen through Western artists and historians appropriating and abstracting these “African” objects. In other words, the value and relevance of these objects had to be manufactured by the West because their supposed value from where they were taken from was illegible. I understand that this is a rather simplified version of how institutional forces work but all of these processes have played a part in terms of what is being made now and how contemporary objects are being received.

It also seems necessary to add that the interest in “identity” from the othered subject is connected to the discourse of race, therefore exposing how whiteness is produced and functions: firstly because those who identify with whiteness are perceived as occupying the norm – a subject-position that is perceived as already understood; second, whiteness is connected to the construction of race and structural complicity within a system that intentionally and unintentionally supports and justifies white supremacy. Pared down, whiteness has been defined as a position in a power relationship that builds itself in opposition to all the people who are produced as non-white, and uses moral rhetoric and institutional forces to defend and systematize exploitation, racism, mass murder, and crimes of the empire. Some theorists rightly argue that whiteness is a form of capital that is not always apparent but can be traded in at any time. Therefore, to treat whiteness as the unspoken norm is to fail to see precisely how those who are perceived as white have systematically acquired this capital, buttressed by the particularities of the law. In sum, to quote Homi Bhabha, “Whiteness is held up by the histories of trauma and terror that whiteness must perpetrate and from which it must protect itself; the amnesia it imposes on itself; and the violence it inflicts in the process of becoming a transparent and transcendent force of authority.”

Meleko Mokgosi, Acts of Resistance. Exhibition view at The Baltimore Museum of Art, 2018. Courtesy the artist and The Baltimore Musuem of Art.

So I think all of these histories and frameworks compel an investment in identity from many sides, but most importantly, I think the inability to conceptualize “our” experiences outside of Western humanism is a driving force in the fixation on “identity and identity politics”. After all, Western humanism argues for the secular notion that history is something that is produced and can be rationally understood by the human subject. Therefore, class identity, racial identity, gender identity, sexual identity, cultural identity etc. are all conceptualized under the organizing principle of humanism (not forgetting connections to neo-liberal ideological structures).

C&: How would you refer to your practice when exploring subjects related to your culture or identity? How is it relevant to speak about your work in these terms?

MM: My artistic practice, to use the popular phrase, can be simply defined as a project-based studio practice. This definition came from working closely in graduate school with conceptual artist and educator Mary Kelly. The term project-based is specific here because it does not refer to project as a theme or topic around which a body of work is made. Rather ‘project-based’ describes the whole artistic approach to developing that which the artist wishes to say. Put differently, project-based outlines how a specific constellation of discursive frameworks come together, and the questions that arise from interrogating the point at which those discourses intersect. I would describe my project as one that is centered on various southern African nationalist movements in both their emergent and subsequent forms. Because the southern African nationalist movement functions as the discursive site, my work will always be informed by post-colonial studies and Marxism, while the rules of the studio are generated by history painting, cinema studies, and psychoanalysis.

All in all, the question of representation, both literal and conceptual, is key. And some of this is reflected in a recorded James Baldwin lecture I heard recently. In a public lecture titled ‘The Moral Responsibility of the Artist’ delivered in 1963 at the University of Chicago, the renowned writer and intellectual made a simple yet powerful statement: namely that the artist, needed and produced by a community, “is somebody who helps others see reality again.” That is, the artist is a historically conditioned and culturally specific subject who questions the taken-for-granted and normative bodies of knowledge and assumptions about both the observable and invisible aspects of reality. The last word in his phrase, “again,” is important because it highlights the fact that given the ways in which the human subject is constructed and negotiates the world, it is impossible to always have access to reality or realities. Representation then, both abstract and otherwise, is an important factor in the continuous efforts to pull individuals towards reality. As an educator and artist, my approach is rooted in the belief that questions around representation and the human body are crucial because subjectivity is not just about ideas and theories, but more importantly it involves the materiality of the body together with its psychic and emotional realities. Put differently, my work engages with subjectivity as a felt experience so as to highlight the body in languages that are necessarily tied to the specificities of lived experiences, untraced histories from the periphery, and work against the already established narratives within which certain subjectivities, peoples, and cultures are stereotyped, violated, and misrepresented.

Meleko Mokgosi, Acts of Resistance. Exhibition view at The Baltimore Museum of Art, 2018. Courtesy the artist and The Baltimore Musuem of Art.

C&: When artists from Africa and the Diaspora explore themes beyond their “identity”, for example a conceptual artist from Accra focusing on Bauhaus, they are often questioned in a way white artists would never be. How do you think this can be challenged?

MM: I believe it is almost impossible to see how any artist can go beyond anything having to do with their identity because the formation of subjects has to involve subjection, to use Foucault’s term. So everything we do is an echo of this process, thus it is difficult to see how any one action or investment is separate from our identities. The problem then would be the fact that identity is understood in very specific terms and the art historical context seems to have an inclination towards only hearing specific things about a narrow conception of identity, meaning that everything else will remain in the periphery. I think the first way to challenge this is to try to reformulate the problem because we already mostly understand the epistemological and methodological limits of this Eurocentric discourse and why it is fixated on the identity of the othered subject.

So, in a way, I am proposing that instead of asking what should be done with the fact that there is always a perverse interest in the identity of the non-Western artist regardless of what she makes; rather let’s propose asking what this perversion reveals about the limits of the discourse and what could be used to supplement these limitations. Put another way, the limitations that produce these narrow interests are not caused or aligned with the object or the artist but rather with the methods of analysis and historical baggage of the reader. Or, since we already know why there is a fixation on the identity of the othered artist, then what does this reveal about the asymmetrical nature of the reception, analysis, consumption, commodity speculation, and pedagogical framework of the field? And, equally important, how does this fixation and asymmetry affect what and how these artists (myself included) produce art objects? So the emphasis on the identity of the not-white artist versus the lack of interest of the white artist clearly reveals the mechanisms through which whiteness reproduces itself; and as long as this continues to happen, the field of the fine arts will remain uninterested in expanding the notion of the subject of history because, as far as it is concerned, the subject of history is something that is already understood and spoken for. Therefore, the field needs to develop the tools and methods of conceptualizing why and how other artists are trying to re-articulate and add to our understanding of the subject of history.

Interview by Will Furtado.

Meleko Mokgosi: Acts of Resistance continues through November 11 at The Baltimore Musuem of Art.

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas