Mabel Cetu: A Complicated Legacy

L’autrice Ethel-Ruth Tawe s’interroge sur les multiples récits liés au travail photojournalistique de Mabel Cetu, en particulier l’analyse de Stephanie Jason développée dans Centring Silences autour de l’absence de Cetu dans les archives.

To pose the question “where are the African women imagemakers in history?" is both a provocation and an open call. When so little is traceable from the shadows that women have been subjected to, we must listen to the silences of institutional archives and turn to the disruptive potential of “unofficial accounts.” It is a careful task of resurrecting histories without reducing them to mere statistics against a mainstream measuring stick; it is the endeavor of speculating without reconstructing bias. In her reader Centring Silences: The Elusive Photographic Archive of Mabel Cetu (Faculty of Humanities, University of Witwatersrand, 2020), Stefanie Jason examines the multiple narratives that construct an image of a woman often titled as “the first black South African woman photojournalist.” Dominant history-making practices of “firsts” often reinforce “Western desires of ‘discovering’, ‘defining’ and ‘viewing’” while perpetuating exclusionary colonial sentiments, according to Nontobeko Ntombela and others in a now sizeable lineage of South African women who have reckoned with Cetu’s legacy. To problematize such titling is to expose the long-standing process of classifying histories into recordable or omittable. It is another framework of violence embedded in the archive, especially against women, in the layered sociopolitical climate of a place like South Africa.

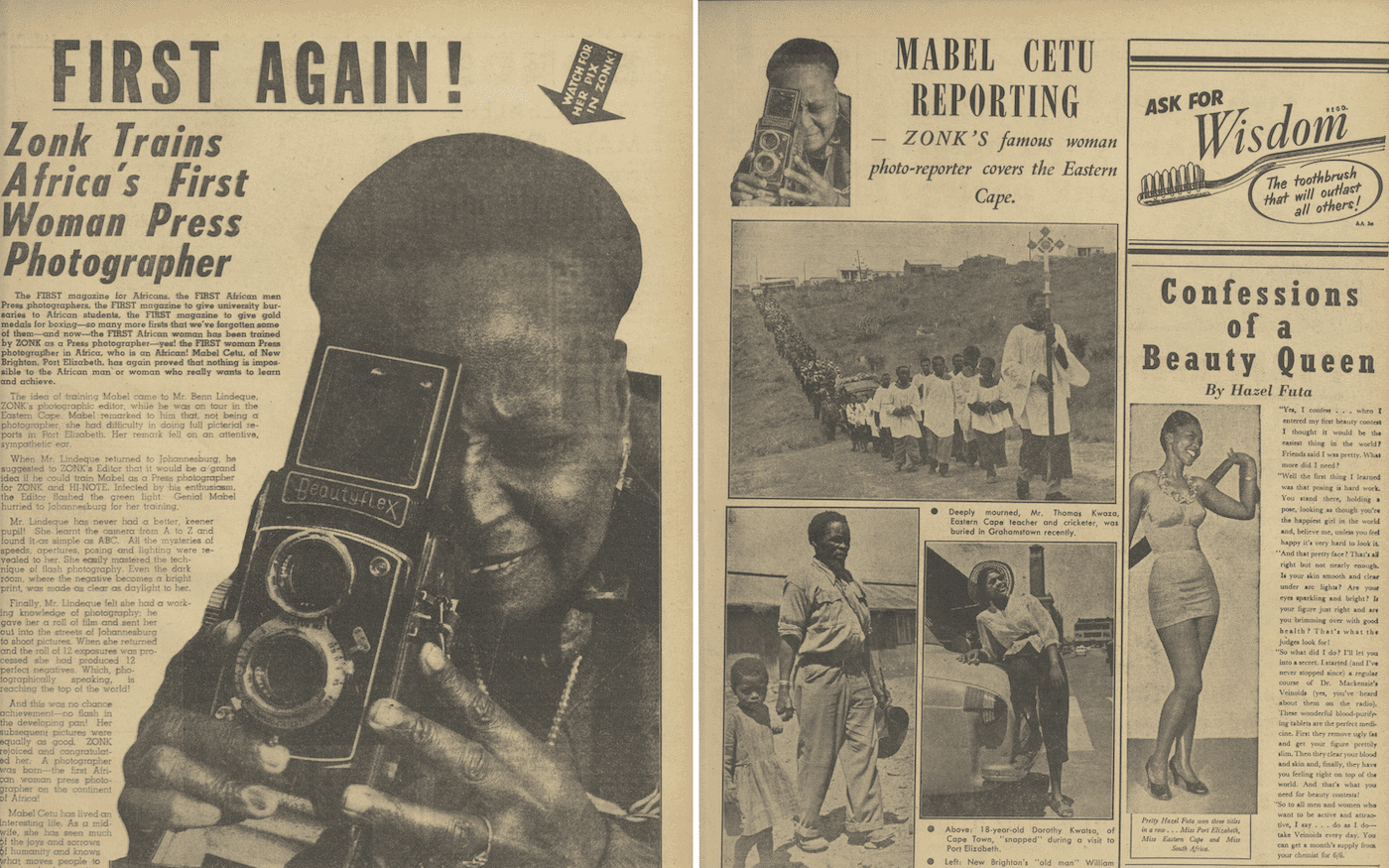

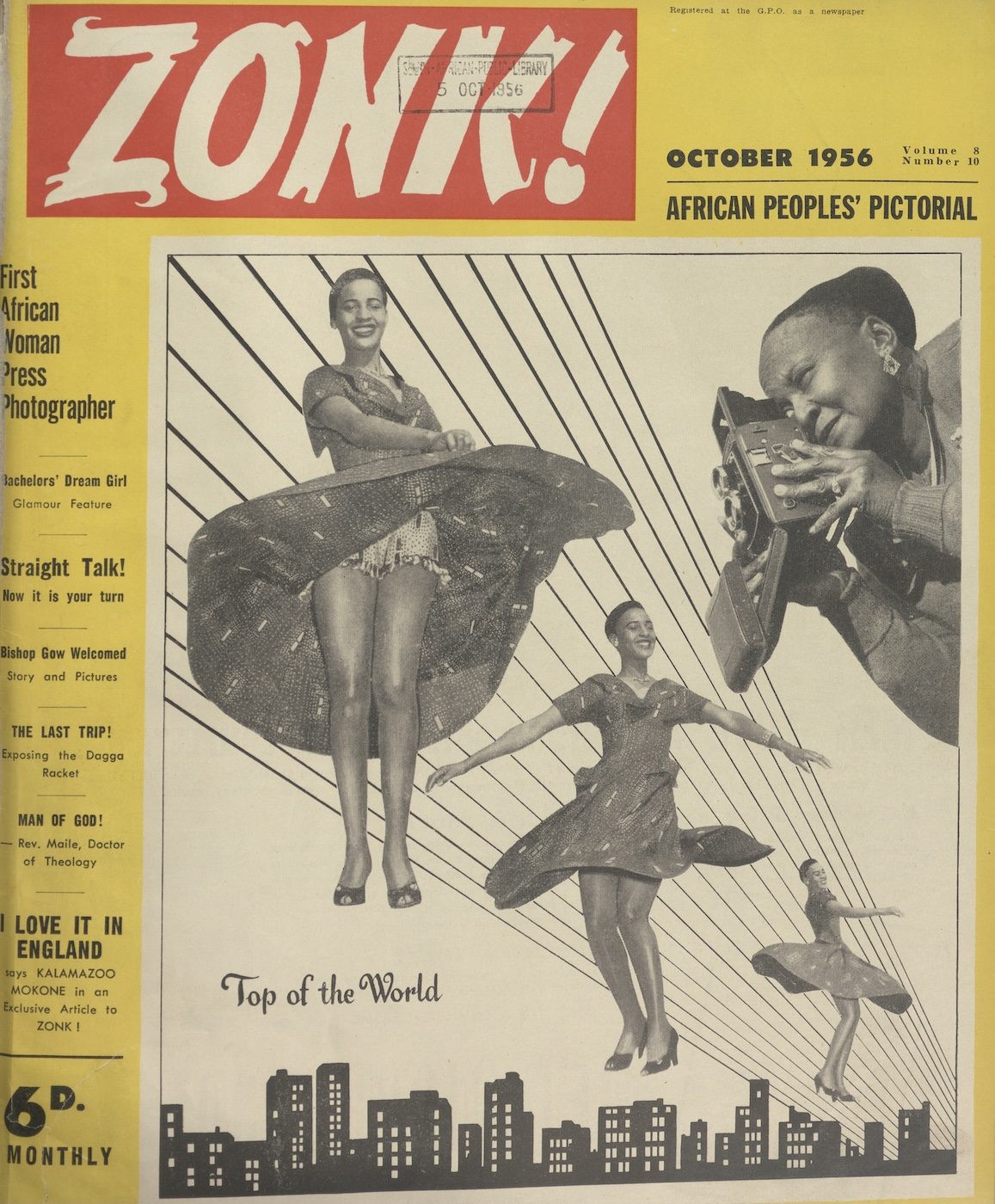

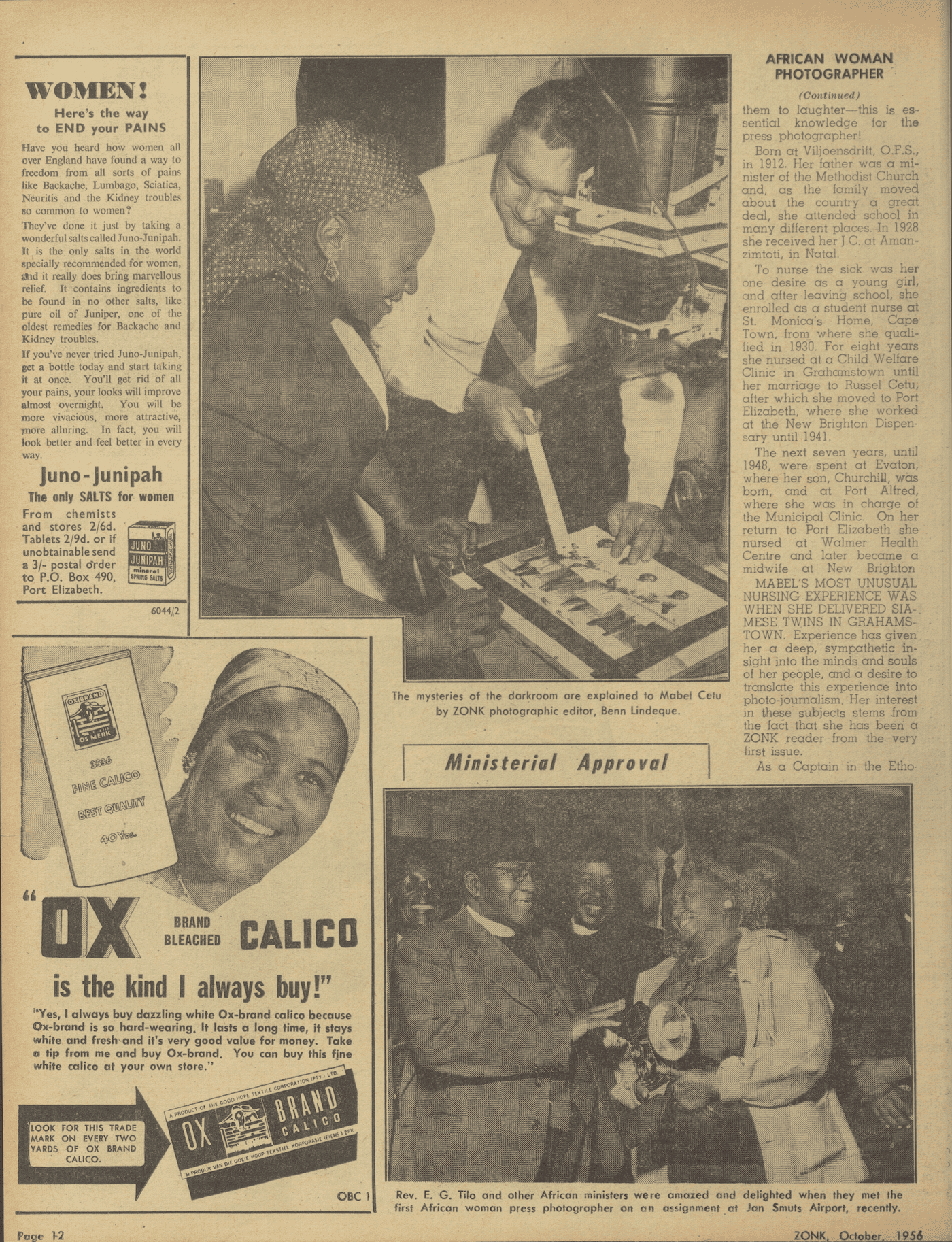

Front cover of Zonk! African People’s Pictorial, October 1956. Photographer unidentified. Photo Courtesy of the National Library of South Africa Cape Town.

Mabel Cetu (born Sidlayi) was a nurse, councilor, community organizer, and broadcaster – competences that transferred into her photojournalistic practice through approaches of care and curiosity. Affectionately known as “Sis May,” she was born in 1910 in Orange Free State, later settled in New Brighton, Port Elizabeth (now Gqeberha), and died in KwaDwesi in 1990. Cetu received her photography training at Zonk! magazine, as announced on the cover of their October 1956 issue. She also worked for Golden City Post, Drum magazine, Usombomvu (the Herald’s weekly title), and state-run Radio Bantu, among other outlets and publications with significant Black readership. Opposing accounts of who she was and what she stood for may or may not explain the deafening silence around her in historical records. On the one hand, Cetu is noted for her political activism against the apartheid government; and on the other hand, she was a reputed figure among the white population. According to her niece Zingiwe Cetu, Mabel Cetu was appointed as “community councilor” or “Black Local Authority” (BLA) for the Khayamnandi Town Council in the early 1980s, a role developed under apartheid to concede some power to African communities. Such appointments were strategically granted to individuals by the apartheid state, which brings up questions around Cetu’s stance and possible grounds for omission in post-apartheid records. That controversial position led to an attack on her home in 1985, and her ensuing resignation from politics.

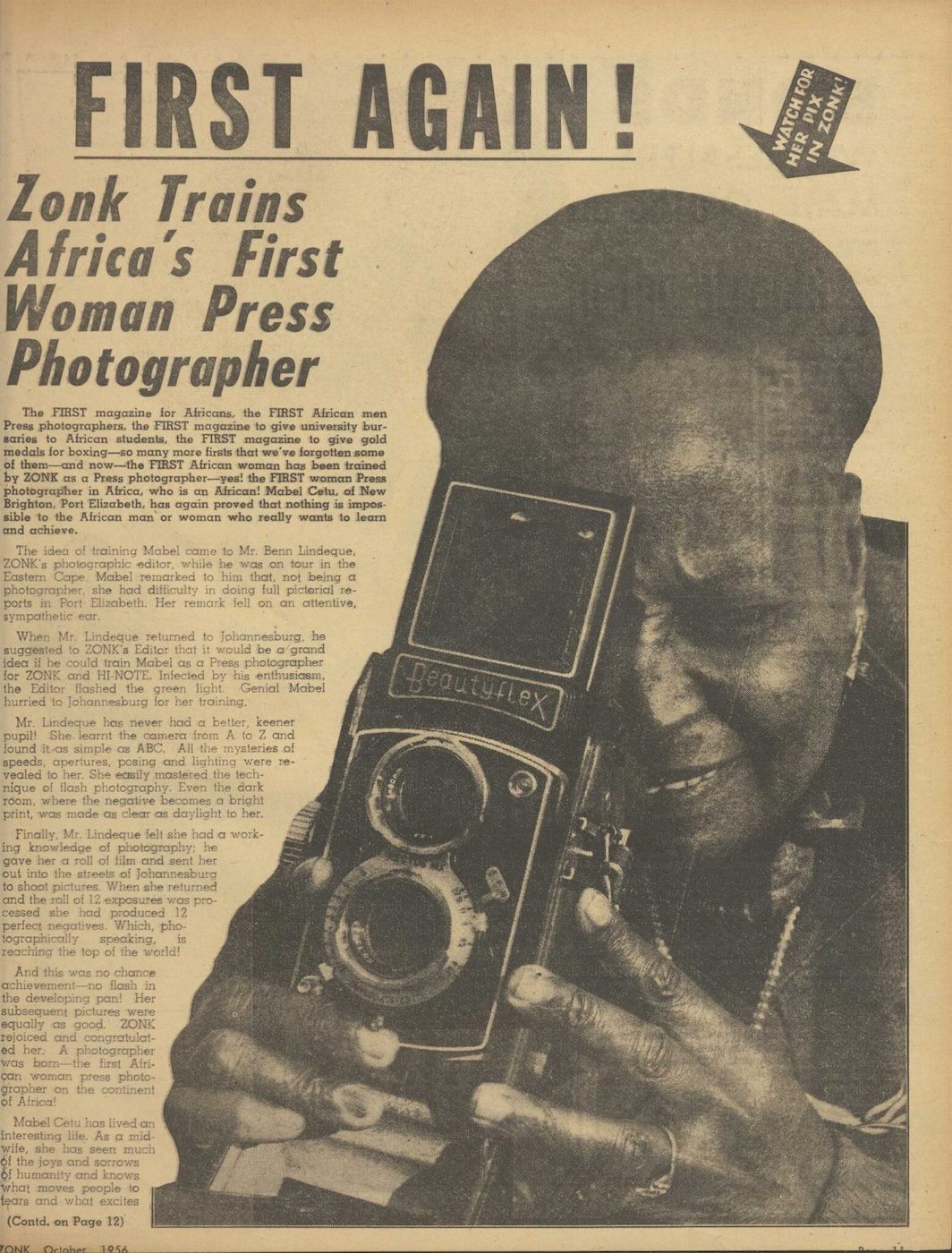

Mabel Cetu featured in Zonk! in October 1956.

It is worth considering that throughout history African women have adopted tactfully diplomatic and often risky strategies to advance their aims. In the seventeenth century Queen Nzinga (of what is now northern Angola), for example, married to form military alliances and encouraged conversions into Christianity to gain recognition from the Catholic pope in Rome and therefore autonomy over her land during colonial rule. While details remain speculative and gaps permeate such narratives, attempting to unpack their internal reckonings is a useful, if at times implausible, task. Subversion and defiance underpin the practice of such women, although we remain only with fragmented records, and primarily of those from high social status. Cetu’s high visibility, however, contrasts with her near absence from records, prompting the question of whether her dismissal into the fringes was due to her failure to fit into dominant configurations of South Africa’s history.

Mabel Cetu featured in Zonk! in October 1956.

In pointing out that “after 1948 African photographers became visible protagonists in shaping the image of their world,” curator Okwui Enwezor highlighted the poignancy of the apartheid period. And unlike contemporaries such as Ernest Cole and Peter Magubane, Cetu had additional patriarchal structures working against her. Despite her recognition and photographic evidence of her operating a camera, very few photographs have been explicitly attributed to Cetu. The practice of anonymous photography in publications like Drum magazine, combined with lack of credit to women in the publishing space, reinforced conceptions of authorship from a masculinist model. In the exhibitionDefiant Visions, curated by Marie Meyerding, a selection of photo spreads retrieved from Zonk! magazine’s archive illustrates the early days of Cetu’s appointment there, focusing heavily on her title as “first” as well as on the efforts of her editor Benn Lindique. In a photograph of them together, the caption suggests that Lindique is explaining “the mysteries of the darkroom.” The 1956 issue features statements that her photographs are “equally as good” and a hyperbolic emphasis on “the first African woman press photographer on the continent of Africa!” as well as gendered undertones in mentions of her work as a midwife. While celebrating her achievement is important, it is just as important to open up what such announcements actually mean and their possible underlying marketing objectives.

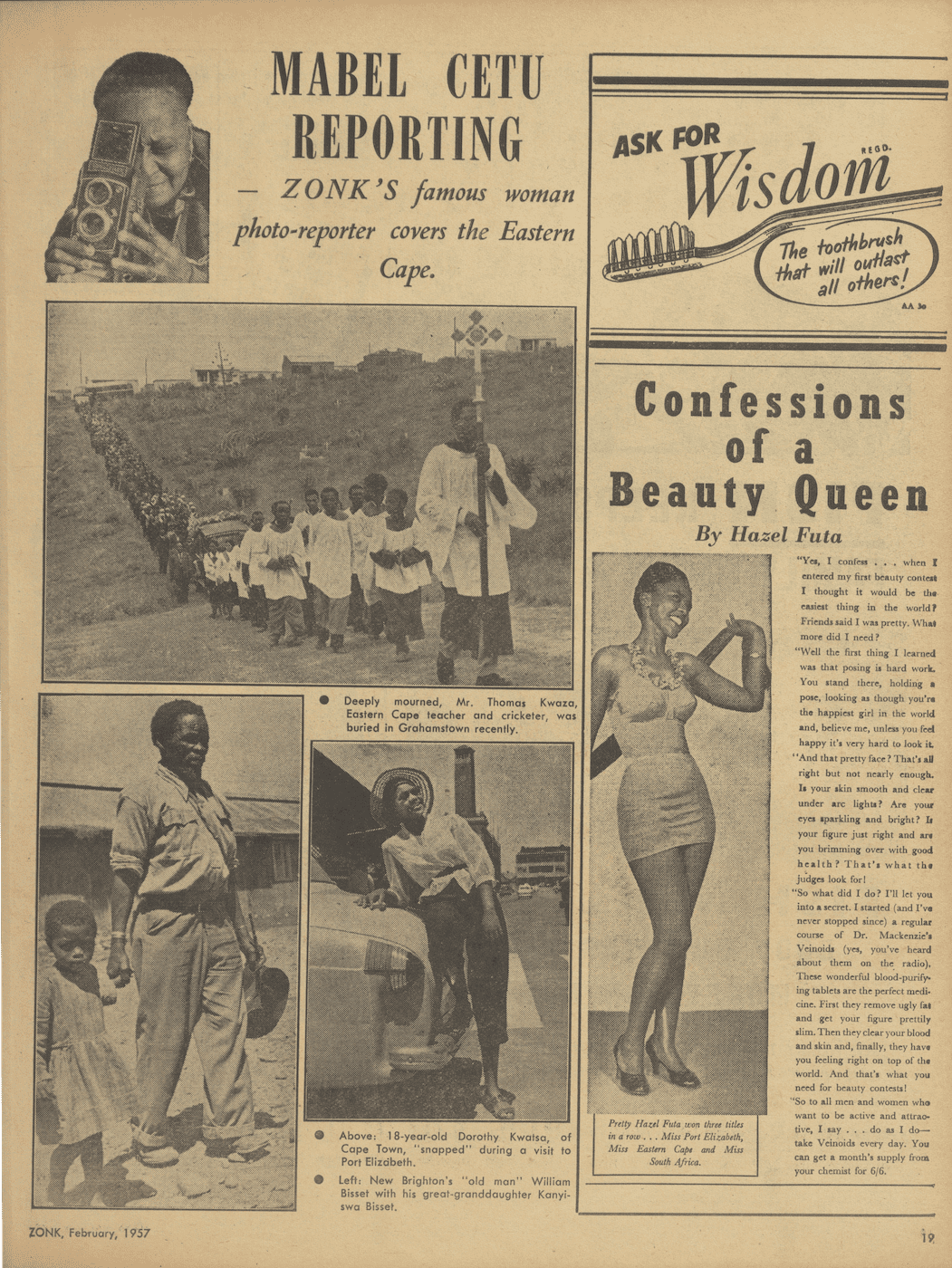

Mabel Cetu featured in Zonk! in February 1957.

The nebulousness of the findings on Cetu in institutional archives speak volumes on how silence can resonate. Black feminist memory work in projects like Centring Silences highlight how the quotidian, the vernacular, and oral tradition may offer resolve. Combing through Cetu’s work also offers a visual window into ordinary life while the majority of photographs exported from South Africa at the time portrayed struggle exclusively. Mabel Cetu lived at a time where her identity and work meant she had to maneuver tactfully, and this projects into her afterlife and complicated legacy. Nonetheless, traces of her story are critical in understanding the erasure and the contributions of African women in the politics of image-making.

Ethel-Ruth Tawe is an image-maker, storyteller, and time-traveler based between continents. She is a multidisciplinary artist, curator, and writer exploring memory and archives across Africa and the Diaspora.

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Identity

Kombo Chapfika and Uzoma Orji: What Else Can Technology Be?

In Conversation with Lubaina Himid: The Artist Set to Represent the UK at Venice Biennale 2026