Lina Ben Rejeb: Pushing the Limits of Erasure

21 September 2021

Magazine C& Magazine

8 min read

Having graduated from the Beaux-Arts de Paris in 2011, Lina Ben Rejeb has built her career in France and Tunisia, while aspiring to a form of universal expression. Working with protocols, the artist experiments with materials, tools, and machines, degrading them to the point where they become exhausted and lose meaning, the idea being to …

Having graduated from the Beaux-Arts de Paris in 2011, Lina Ben Rejeb has built her career in France and Tunisia, while aspiring to a form of universal expression. Working with protocols, the artist experiments with materials, tools, and machines, degrading them to the point where they become exhausted and lose meaning, the idea being to create a new language that is inherent to the work itself. Never adopting a head-on approach, she takes a roundabout route, one that is deconstructive and suggestive. In order to defy death and cheat oblivion, the artist hunts down finitude and the remnants of what is being exhausted. She invites us to her Parisian studio to discuss this.

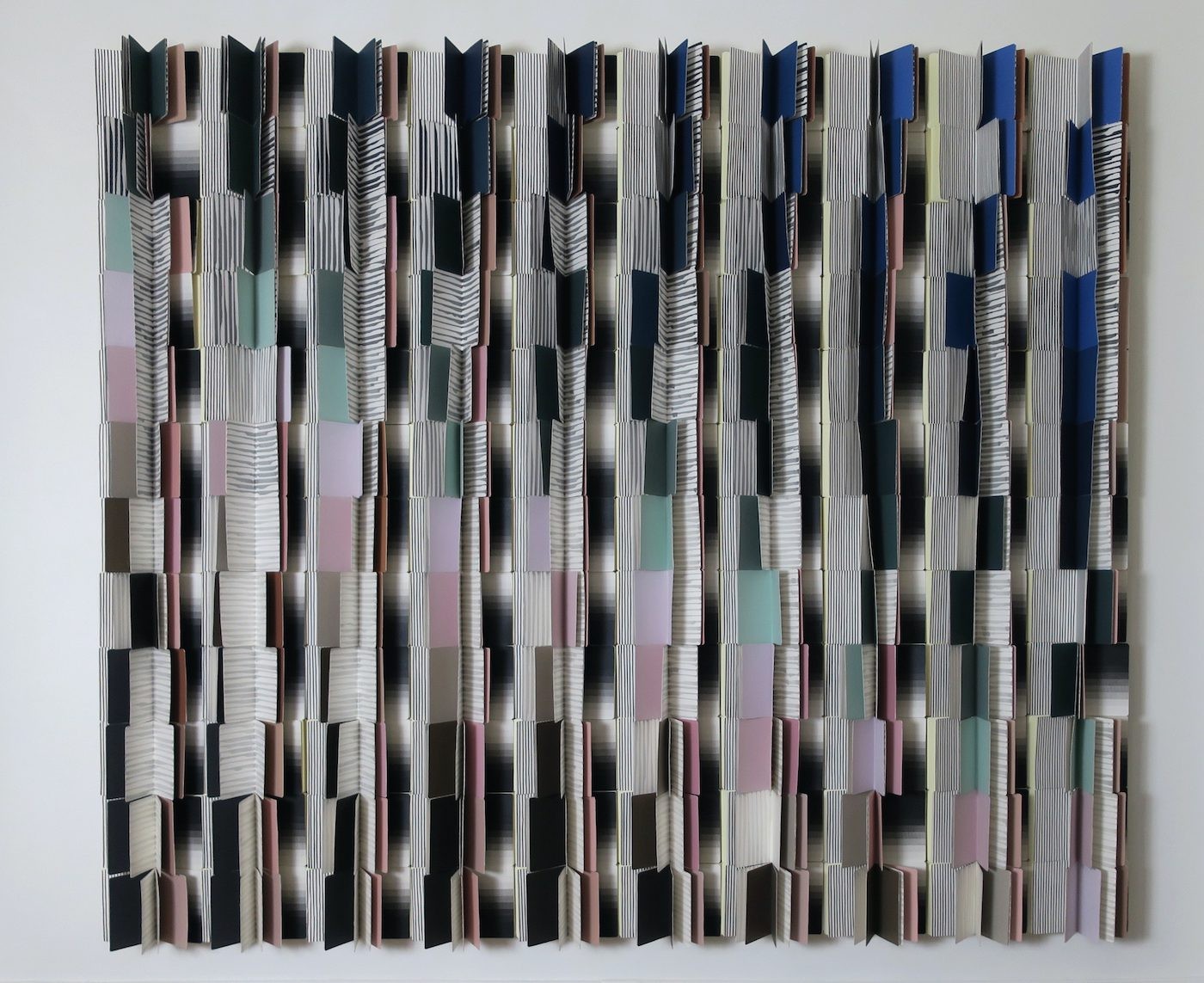

<figcaption> Lina Ben Rejeb, Layering, 2017. 151x176cm, mixed technique on paper. Courtesy the artist.

Contemporary And : Your career has seen you moving between France and Tunisia. How has this trajectory forged your relationship with language?

Lina Ben Rejeb: I had the opportunity to study in two languages: Arabic and French. When you’ve lived in Paris for 15 years and no longer had much chance to speak Arabic, what’s left are the books. I wasn’t able to travel as a child, so reading allowed me to create worlds, to discover the magic of thinking in images, and then to learn how to compare what I had constructed with reality. Tackling other people’s memories is surely the best way of approaching a culture, before addressing it as a living, human phenomenon.

When I arrived at the Beaux-Arts, having taught myself in a rather classical style, I was more interested in the conceptual aspect of art. At that time, though, there weren’t many artists from the Maghreb at school and right away the people running the studios wanted to go further in the direction of calligraphy, which I reacted against. I then chose to do things back to front by deconstructing my relationship to writing so as to move towards a different linguistic materiality. Before arriving in France, I had studied design for two years, including a year of calligraphy. What immediately interested me, rather than the plastic beauty, was the idea of rigour in repetition, which creates a form of echo, a kind of metagesture. This is what we find in my Carnets (notebooks), where this lack of meaning in the calligraphic gesture generates its own vocabulary.

The issue of the finite nature of writing as a gesture went on to become a central concern in my practice.

<figcaption> Lina Ben Rejeb, Les Petites mains 4 et 5, 2020. Wooden stamps, acrylic paint. Courtesy the artist.

C&: Why do you refuse to be pigeonholed as an Arab artist?

LBR: Even if the postcolonial or identity questions are very interesting ones and it is important to interrogate the past and your relationship to the country you choose to settle in - just like it’s important to examine questions of feminism - I consider these to be personal matters. There’s no obligation to be exotic. What the Casablanca Biennale offers us is a framework that goes beyond the question of identity and goes beyond Africa, even if it is a continent that needs to be looked at, and looked at in a different way. I am not a political artist, and my work is not autobiographical, at least not for the moment. What I am interested in is in setting down a form of language that will create relationships, while at the same time keeping myself separate. I like this distancing, vis-à-vis the image and the narrative. In my approach, it is important for me to be able to talk to everyone, which may be part of a rather absurd quest for universalism. From the start, it has been a question of decontextualizing myself in order to locate other countries, other languages, other encounters. I like to have multiple audiences, from different sociocultural backgrounds and different countries, where the interaction nevertheless remains constant. Incidentally, this is what has always interested me in museums, this way of removing oneself from the world.

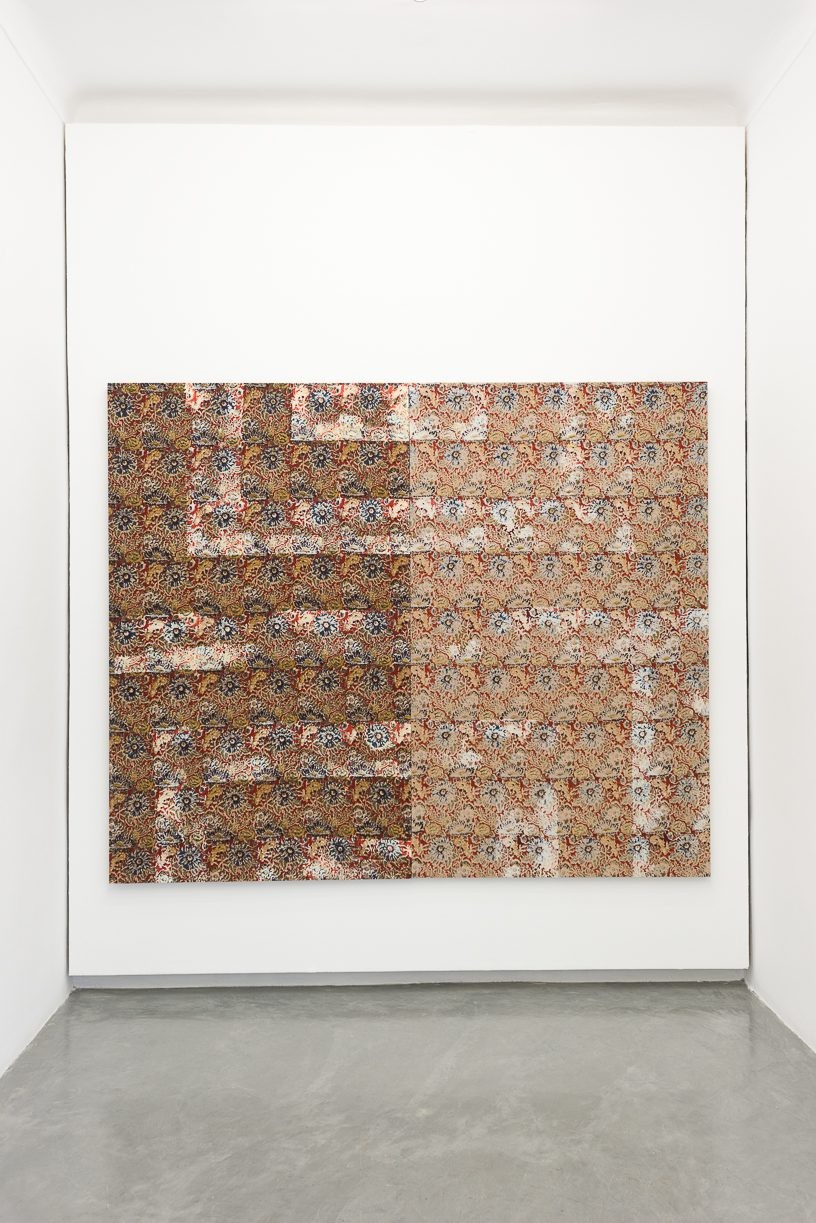

<figcaption> Lina Ben Rejeb, Peintures domestiques No. II (Diptych) , 2019. Indian fabric, DMC embroidery thread, 204h x 123w x 4d cm, Unique. Courtesy the artist.

Perhaps the only exception to this is in my series Peintures domestiques (Domestic Paintings), which you could consider feminist insofar as I question the notion of “women’s work,”

Peintures Domestiques I and II Peintures Domestiques reveal a manual way to erase by bleach washing. Then I erase the erasure in a tautologic gesture by seaming. To reveal the erased motif is revealing the properties of this fabric: it is composed by strata, a way of producing quite close to the artistic production and which soon will no longer be.

And to answer the question, I have a problem with the idea of defining a person depending on their origins. An artist should not be assigned to an identity, to a context. I see my work not as a negation of who I am but as an extension, a move toward the others.

<figcaption> Lina Ben Rejeb, Nous sommes de cette étoffe dont les rêves sont faits II, 2020. Detachment of pictorial layers, entomology showcases 50 x 39 x 7cm each. Courtesy the artist.

C&: Your approach involves an attempt to answer questions about the meaning of the work, of oblivion, of the vestige, while deconstructing the very idea of meaning and accentuating an immediate relationship between the audience and the work …

LBR : Making sense is probably one of the most difficult things to achieve, but it is also one of the easiest ways to approach art, which is rather a terrifying prospect from the outside. To keep your nerve, you have to come at it from a conceptual angle using simple questions and operating with gradual shifts of meaning to avoid a head-on approach. Afterwards, I always give a talk to accompany the work - which can sometimes seem hermetic - because it is important to me that people understand. However, my point of view is partial or prejudiced. I put it out there, but I don’t impose it. I want the spectator to come and be with the works and I like it when they have their own way of operating. The most beautiful gift you can give an artist is to approach their work without permission and without asking any questions. This shows that a bond of trust has been created, when, in general, works impose distance.

<figcaption> Lina Ben Rejeb, Couverture Muette No. VIII, 2019. Entomology display box, old book cover, 45h x 35w x 7d cm

Unique. Courtesy the artist.

C&: How do you explain the paradox between this search for finitude and the desire to fight against death, to struggle against the object being forgotten?

LBR: The series Couverture muette (Mute Cover) involves entomological display cases - typically containing butterflies or flies - in which I place old book covers. These showcases, which are designed to present something elusive, still contain traces of what is dead and thus offer a double tautology of death, a double non-usage, cocking a snook, in a way, at the ready-made. The book, when empty, loses its meaning, its material, and its function: instead, it questions the representation of death, the attachment to the past, and the need for preservation.

Finiteness and exhaustion are at the heart of my entire approach. One of the first things that led me to this was the pen stroke, the ink that runs out and disappears. But we don’t distance ourselves from the concept of beauty because we make conceptual art. I need people to feel a kind of pleasure when faced with my work. So one can speak of finitude while being attached to a form of positive presence in the gaze. I fight against oblivion by pursuing it, by displaying it. Finding the subject, going in search of it, but starting from the end.

Lina Ben Rejeb will take part in the nextCasablanca Biennale, which has been postponed to 22 September - 5 November 2022.

Chama Tahiri Ivorra is a creative director, producer, and journalist based in Casablanca and Paris.

Read more from

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

Confronting the Absence of Latin America in Conversations on African Diasporic Art

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

Read more from

(RE)COUTURE

Political Issues and the Relationship with the Occult