Laboratoire AGIT’art and Tenq in Dakar in the 1990s’,

In the space of three weeks between April and May 1996, the parallel histories of Chinese migrant labour and Senegalese art practice unexpectedly overlapped to produce an event in Dakar that would leave permanent traces in the landscape of the Biennale. The former Minister of Culture, philosopher and writer Abdoulaye Elimane Kane, handed artist and …

In the space of three weeks between April and May 1996, the parallel histories of Chinese migrant labour and Senegalese art practice unexpectedly overlapped to produce an event in Dakar that would leave permanent traces in the landscape of the Biennale. The former Minister of Culture, philosopher and writer Abdoulaye Elimane Kane, handed artist and curator El Sy, who headed the collective TENQ, and I the keys to a disused Chinese encampment near the airport.

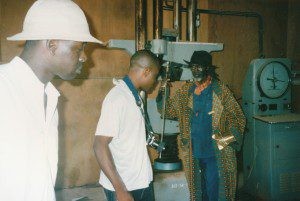

<figcaption> El Sy, Chika Okeke and Issa Samb visiting the brick-pressing plant. The Chinese laborers produced the bricks for the sports stadium, 1996. Photo: Clémentine Deliss

When we took over the site, there was no running water or electricity. Eleven barracks were subdivided into small sleeping chambers for five hundred workers and, in addition to a large refectory and bathroom units, there was a press for producing bricks, stocks of ginseng and piles of maps and technical drawings, all in Mandarin. In the early 1980s, the Chinese government was commissioned by numerous West African states to design and build sports arenas in exchange for diplomatic support and trade privileges. The Chinese brought their own labourers to Senegal and built temporary housing for them in the suburbs of the city. Once the construction was completed, most of the Chinese left Senegal. Those who stayed in Dakar moved out of the camp, and it remained uninhabited for over eight years. The camp had its own sophisticated system of irrigation and a profusion of mango trees, but it was rundown and needed cleaning up.

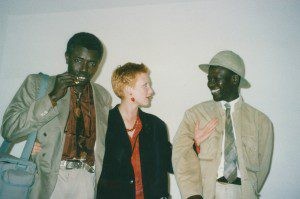

<figcaption> Magaye Niang, Clémentine Deliss and El Sy preparing for a meeting with the Minister of Culture, 1996. Photo: Mor Lyssa Bâ

Three weeks later, in May 1996, TENQ, understood as a point of artistic connection, opened the gates of the Chinese camp to the outside world. The flimsy dividing walls in the barracks had been knocked through and studios allocated to guest artists from Kenya, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Ivory Coast, Nigeria and the UK, who spent two weeks living and working together on site. A gallery space was set up in the former canteen and a manifesto announcing the opening was pasted onto the shed walls. TENQ 96 had an inflammable character, fighting for a new identity between the local history of artists’ squats and government evictions, on the one hand, and the demands for high visibility and accelerated production that new internationalism commanded on the other. Although the occupation of the site was not intended to continue beyond the two-week session, El Sy and the core group never left the new Village des Arts, and several have been based there ever since. This nearly untouchable situation has provided the city of Dakar with an arts infrastructure that remains the only initiative related to the Biennale to have survived throughout the years.

<figcaption> Clearing up the camp El Sy explaining what needs to be done with Chika Okeke watching on April 1996. Photo: Clémentine Deliss

This extract is part of 'Brothers in Arms: Laboratoire AGIT’art and Tenq in Dakar in the 1990s', an essay by Clémentine Deliss forthcoming in AFTERALL, issue 36, Summer 2014.

Clémentine Deliss is director of the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt am Main. She studied contemporary art and social anthropology in Vienna, London and Paris and holds a PhD from the University of London. From 1992 to 1995 she was the artistic director of africa95. Selected exhibitions curated by Deliss include: ”Foreign Exchange (or the stories you wouldn’t tell a stranger)”, Weltkulturen Museum (with Yvette Mutumba), 2014; “Object Atlas – Fieldwork in the Museum”, Weltkulturen Museum, 2012; ”Seven Stories About Modern Art in Africa”, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 1995, and Malmö Konsthall, 1996; “Lotte or the Transformation of the Object”, Styrian Autumn, Graz, and Akademie der Bildenden Künste Wien, 1990; Between 1996-2007, she produced eleven issues of the international writers’ and artists’ organ Metronome first published in Dakar in 1996. Between 2002 and 2009 she directed the international research lab Future Academy launched in Dakar.

Essay

The Museum of Black Futures

Caribbean Sounds: The Connective Possibilities of Radio

Black Canadian Print Cultures: Of Quiet and Enduring Legacies

Essay

The Museum of Black Futures

Caribbean Sounds: The Connective Possibilities of Radio