"Killing the Hierarchy Within You"

19 June 2017

Magazine C& Magazine

8 min read

In its 14th edition, documenta is taking place in both Kassel and Athens. Partially offshoring the event did not fail to raise a slew of questions about the legitimacy of its concept of expressing the desire of “learning from Athens” and creating spaces for resistance and rebellion in response to the economic and migration crises …

In its 14th edition, documenta is taking place in both Kassel and Athens. Partially offshoring the event did not fail to raise a slew of questions about the legitimacy of its concept of expressing the desire of “learning from Athens” and creating spaces for resistance and rebellion in response to the economic and migration crises whose European epicenter is in Athens. Is this just buzz on the part of an institution that perpetually seeks to be the center of attention? Or are they profoundly questioning specific hierarchical structures of dominant power?

Between testimony to the paradigm of Western democracy and a consecration to its prevaricating political representations, documenta 14 aims to spark a collective reflection on the contemporary crises in our societies. The curatorial concept proposed by Adam Szymczyk stems from a desire to decentralize institutions and hierarchical mechanisms of cultural representation. Thus, the philosopher and activist Paul B. Preciado, in charge of programming the public discussion series titled “The Parliament of Bodies,” interrogates our ability as political subjects to exercise our freedoms under the conditions of today’s neoliberalism. “The Parliament of Bodies” was conceived in response to the popular uprising after the Greek Parliament refused to accept the electorate’s majority “no” (ochi) vote in the referendum of 5 July 2015. From that same vein of protest, documenta 14 seeks to destabilize certain normative categories of identity politics (1).

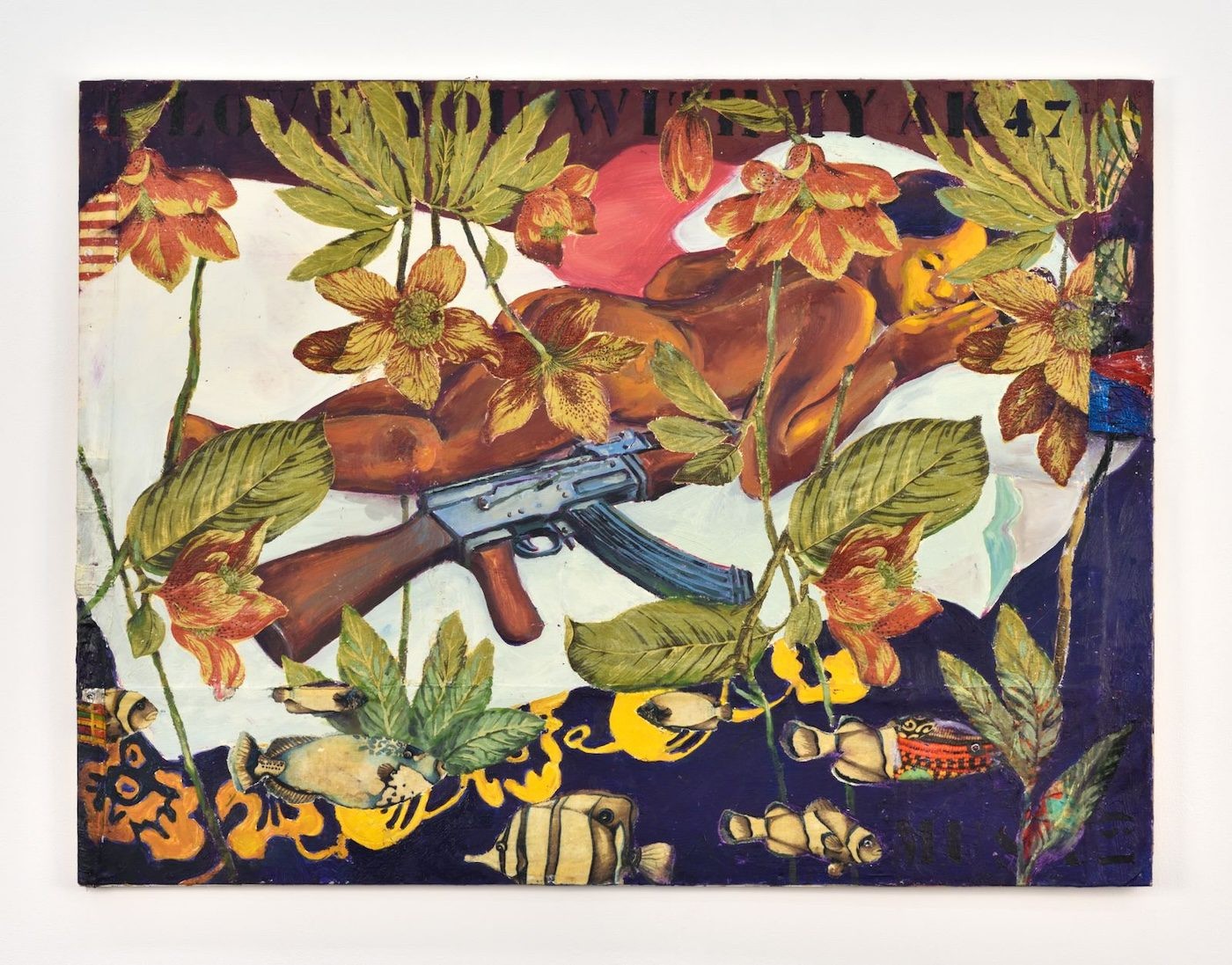

<figcaption> Poster Slogan Can you kill The Hierarchy within you, Athènes Printemps 2017.

Photo © Jorinde Splettstösser.

In this context, their curatorial selection celebrates the presence of artists from African perspectives, including Akinbode Akinbiyi,Sammy Baloji,Otobong Nkanga,Bili Bidjocka,María Magdalena Campos-Pons,Manthia Diawara,Theo Eshetu,Emeka Ogboh,Aboubakar Fofana,Pélagie Gbaguidi,IQHIYA,Bouchra Khalili,Rick Lowe,Ibrahim Mahama,Narimane Mari,Ernest Mancoba,Benjamin Patterson,Pope.L,Tracey Rose,Stanley Whitney,El Hadji Sy,Olu Oguibe,Negros Tou Moria, Kettly Noël, Kendell Geers, and in some respects David Bromberg . Let us not forget the participants outside the main exhibition, such as Doula and the radio interventions of Radio Sport Info; Younes Baba-Ali and Anna Raimondo, who organize Saout Africa(s); and Satch Hoyt and Nastio Mosquito with their sound performances, to name just a few. They are present as part of the program Every Time A Ear Di Soun curated by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung.

<figcaption> iQhiya, The Portrait, 2016, performance, Athens School of Fine Arts (ASFA)— rue Pireos (“Nikos Kessanlis” Exhibition Hall), documenta 14, photo: Stathis Mamalakis

One of the strong points of this documenta is that it invited a number of artists’ collectives to foreground the importance of solidarity when most of the art world makes it difficult for individuals to obtain institutional recognition and equal visibility on the globalized art market. This was the dynamic behind the creation of theiQhiya collective in Cape Town, involving many women who were studying at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, including Asemahle Ntonti, Bronwyn Katz, Buhlebezwe Siwani, Bonolo Kavula, Charity Kelapile, Lungiswa Gqunta, Matlhogonolo Kelapile, Sethembile Msezane, Sisipho Ngodwana, Thandiwe Msebenzi, and Thuli Gamedze. Tired of the lack of recognition of Black women artists in South Africa, they decided to group together to reinforce their visibility. iQhiya comes from the Bantu language of Xhosa and is a symbol for them of infinite love, of a space of solidarity among women. At documenta, iQuiya is presenting Monday (2017), a performance installation featuring school desks and brought to life by video projections in the basement of theKulturBahnhof. Re-enacting memories, they pay tribute to the roles of Black women in resistance movements and join the tradition of such artists as Helen Sebidi and Noria Mabara.

<figcaption> Stanley Whitney, vue de l'installation documenta Halle, Cassel, documenta 14.

Photo © Elsa Guily

What makes art political is not just the content of the work, but foremost the context in which it is interpreted and re-appropriated. Stanley Whitney, with his colorful orchestrations, is a prime example. In the late 1960s, during the anti-racist protests of the Civil Rights Movement, Whitney was exploring abstraction in New York. He draws on the visual polyrhythms of an artist like Cézanne and the auditory ones of Charlie Parker’s jazz, defying structural racism that minimize the visibility of Black artists in the history of American abstract painting.

Another vital work in this edition is Le Fort des fous by Narimane Mari. By visualizing ellipses and metaphors, the film reflects on the displacement and re-appropriation of the telling of history and re-activates memories as resistance strategies. The space of the screen does not go overlooked. On the contrary, it is in flux even in the sculpturality of a mountain of gray pillows that we are invited to plunge into. Sheltered in the old Ballhaus, the onetime residence of King Jérôme Bonaparte, the work can be viewed in comfort, but is also barricaded off in the face of the imposing imperialist history contained in the walls of this Classical-style house. Concluding with a segment from the viewpoint of an Athenian militant interviewed about his experience of resistance to the economic crisis, Le fort des fous retraces the family tree of the capitalist system of exploitation and oppression and locates its sources in the history of imperial, Eurocentric colonialism. The film reminds us that things have not changed so drastically, that these patterns are still present in new economic and political relationships. The systems of cultural domination remain a form of neocolonialism. In the words of the militant, “Civilization, a lot of the time, means death.” The challenge is to construct a body politic amidst our irreconcilable post-colonial differences and also to view history through the lens of its reception and its re-appropriation by way of injured or forgotten memories.

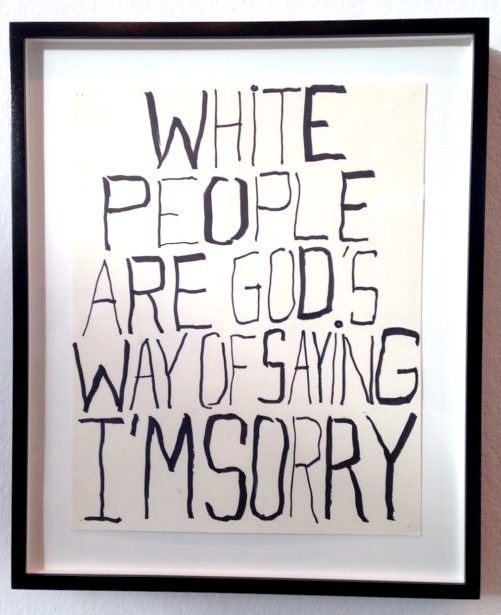

<figcaption> Pope.L, Skin Set Project (1997– ), Tinte, Filzschreiber und Farbe auf Papier , 27,9 × 21,9 cm. Photo: C&

The lesson this documenta clearly takes is that we need to give public recognition to the multiplicity of memories, but at what price? Who recovers this discursive production? What are the implications of such a contradiction – defending practices created directly by schemes of resistance and autonomy within an institutional framework sponsored by the German government and its financial and industrial lobbying groups, the prime investors in the North/South fracture, the financial crises in Greece, and the growing impoverishment of populations? A priori, documenta is poorly placed to appoint itself the mediator of a popular path. But perhaps the ins and outs of this project are all about investigating this very contradiction, of not provoking, in the end, more than a symbolic displacement of tweets, likes, and dislikes. At the opening in Kassel, the Federal President of Germany Frank-Walter Steinmeier took the chance to hail the good democratic functioning of the institution “that does not let itself be politically instrumentalized” according to him, because it is prepared to erect monumental artworks dedicated to refugees and to celebrating the migration crisis, something central to the burgeoning and branching out of of culture after the Second World War. So “Learning from Athens” could be favorable to the transformations of capitalism, commodifying representations of minorities and dissidents in a rhetoric of crisis and a consumerist disaster voyeurism.

<figcaption> Hans Haacke, Wir (alle) sind das Volk—We (all) are the people, 2003/2017, cinq panneaux, vue de l'installation, Friedrichsplatz, Cassel, © Hans Haacke/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017,

To be sure, documenta is not a self-contained entity. For many of its players, it will have been, more than anything, a pretext to pronounce a transition process and express targeted criticisms. This 14th edition understood that its choice of artists was questioning a Eurocentric epistemology of art history. However, as a political institution, its impartiality rests on its elitist imaginary and the insiders’ club of bourgeois norms, as the heated responses of the people in Athens attest (2). Has documenta become apatride (stateless)? Is it undergoing a “slow transition” of escaping its own confines, as Preciado implied? Only our critical faculties can tell us (3). Which is why we must detach ourselves from the many hierarchies within us all (4). The task won’t be easy because, as the Athenian militant makes clear in Le fort des fous, “What I want is totally different from what I hope.”

(1) See Paul B. Preciado http://www.liberation.fr/debats/2017/04/07/l-exposition-apatride_1561303

(2) For a deeper sociopolitical critique of documenta as an institution, and for a brief orientation on the challenges of political and economic history in Greece linked to the polemic of the Athens documenta, read the discussion between Yanis Varoufakis and iLiana Fokianaki: http://www.art-agenda.com/reviews/we-come-bearing-gifts—iliana-fokianaki-and-yanis-varoufakis-on-documenta-14-athens/

(3) See Paul B. Preciado http://www.liberation.fr/debats/2017/04/07/l-exposition-apatride_1561303

(4) Directly inspired by and in reference to the slogan critiquing the presence of documenta 14 in Athens: “Can you kill the hierarchy within you?” The quotation was taken from a poster pasted on a wall in the streets of Athens, spring 2017.

Elsa Guily is art historian and an independent art critic living in Berlin, specialized in the relationships between art and politics.

Read more from

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Irmandade Vilanismo: Bringing Poetry of the Periphery into the Bienal

Read more from

Rest in/as Freedom: kiarita and Black Politics of Liberation

Not for Sale: How Black and Indigenous artists are rewriting the rules of the art market