Imagining a Way Out: Dystopia and Dictatorships

26 September 2019

Magazine C& Magazine

6 min read

The word dystopia needs recontextualization in the surreal and chaotic climate of the United States of America. Oppressive political regimes have been written about through satire and allegories of social discontent for decades. Dystopia, as a literary term, defines a subgenre of science fiction largely popularized through works by the mid-twentieth-century authors Aldous Huxley and …

The word dystopia needs recontextualization in the surreal and chaotic climate of the United States of America. Oppressive political regimes have been written about through satire and allegories of social discontent for decades. Dystopia, as a literary term, defines a subgenre of science fiction largely popularized through works by the mid-twentieth-century authors Aldous Huxley and George Orwell. Works that as a young adult, I sought out and read regularly. Dystopian literature reflected a reality as close to mine as any, and as I assess my own marginalized place in US society, the act of radical resistance becomes ever-important and demanding.

The US empire is heavily surveilled, repressed, and censored – particularly so for Black and Latinx citizens under the current administration. Yet our lives have always been under intense threat through restriction, state terror, distortion, and distrust. In a world where suffering and injustice are basic assumptions, art is able to address the personal and collective trauma inflicted on a population by a government. The recognition of my politicized body has inspired me to explore some of the histories that the dystopian novel calls upon: The very real atrocities of authoritarian regimes in Latin America, and the response of artists who lived through them.

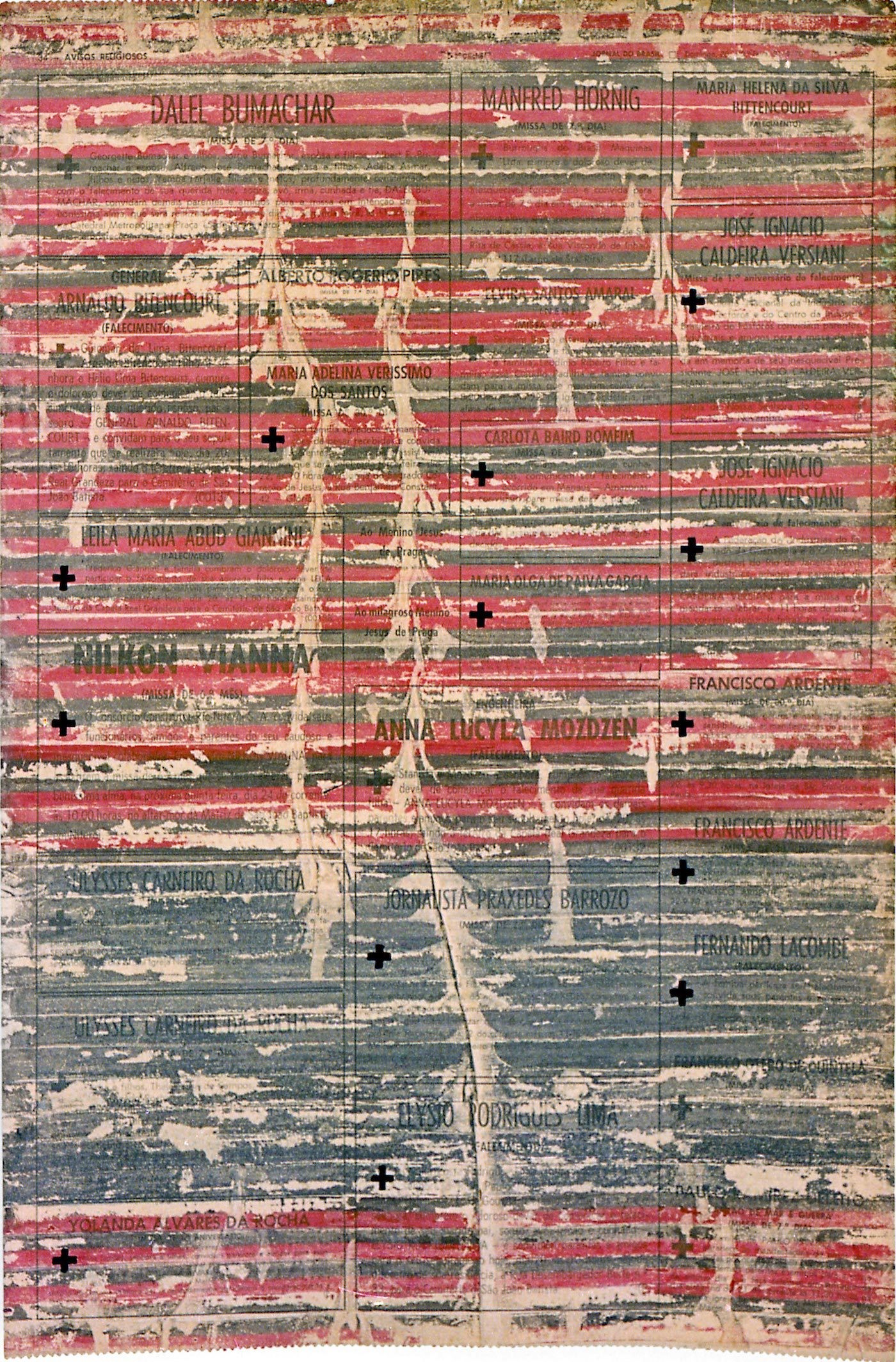

<figcaption> Ana Vitória Mussi, Anuncios (Announcements), from the series Jornais (Newspapers), 1970. Gouache and Ecoline on newspaper, 58 x 38 cm. Collection of Ana Vitória Mussi. © Hammer Museum 2019.

The dictatorships that emerged during the 1960s and 1970s in Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay used fear, surveillance, violence, and persecution to undermine the individual, and aimed to control both the behaviors and bodies of citizens. Artistic expression was stifled and it became necessary to employ elements of symbolism and DIY tactics in art to resist and reimagine an inescapable reality. Artistic practice and political activism merged as governments’ outrages swelled and speaking out against them publicly became too dangerous. Pioneering artists Ana Vitória Mussi, Catalina Parra, and Nelbia Romero continued to use new methods to create in this threatening climate. They bravely and boldly explored the emancipation of the body from the state and used experimental forms of art to call out the crimes of their governments. They used art to critically engage with the political actions of their societies and, in doing so, took an active stance against the resulting oppressive atmosphere. Their works are a historical testament to horrific events, and they were fundamental to their countries’ underground radical resistance movements.

The artworks of Mussi, Parra, and Romero were created over the course of twenty-five years of military dictatorships in Brazil (1964–85), Chile (1973–90) and Uruguay (1973–85). Their existence can inspire artists in any country where fear-based administrations are in place. The joy and pleasure in allowing the body – particularly the female-presenting body – to create space in society through performance and production, instead of bending to authority, is a testament to these powerful tools of resistance.

<figcaption> Catalina Parra, Diario de vida (Diary of life), 1977. Plexiglas, newspapers, plastic fishing wire, twine, 30.5 x 40.6 x 12.7 cm. Collection of Isabel Soler Parra. © Hammer Museum 2019.

Newspapers have long played a crucial role in the dissemination of state-sponsored propaganda, but when used by Parra and Mussi they became a strategic material to combat the disinformation spread to confuse and frighten targeted communities. Under the venomous rule of Augusto Pinochet, self-taught artist Catalina Parra (b. 1940), subverted the power of text through the use of newsprint, press clippings, and collage. Diario de vida (Diary of Life, 1977) uses El Mercurio newspapers layered between two slabs of plexiglass, a time capsule documenting the suppression of language throughout Chile’s dictatorship and illustrating the pressures of submitting to such force.

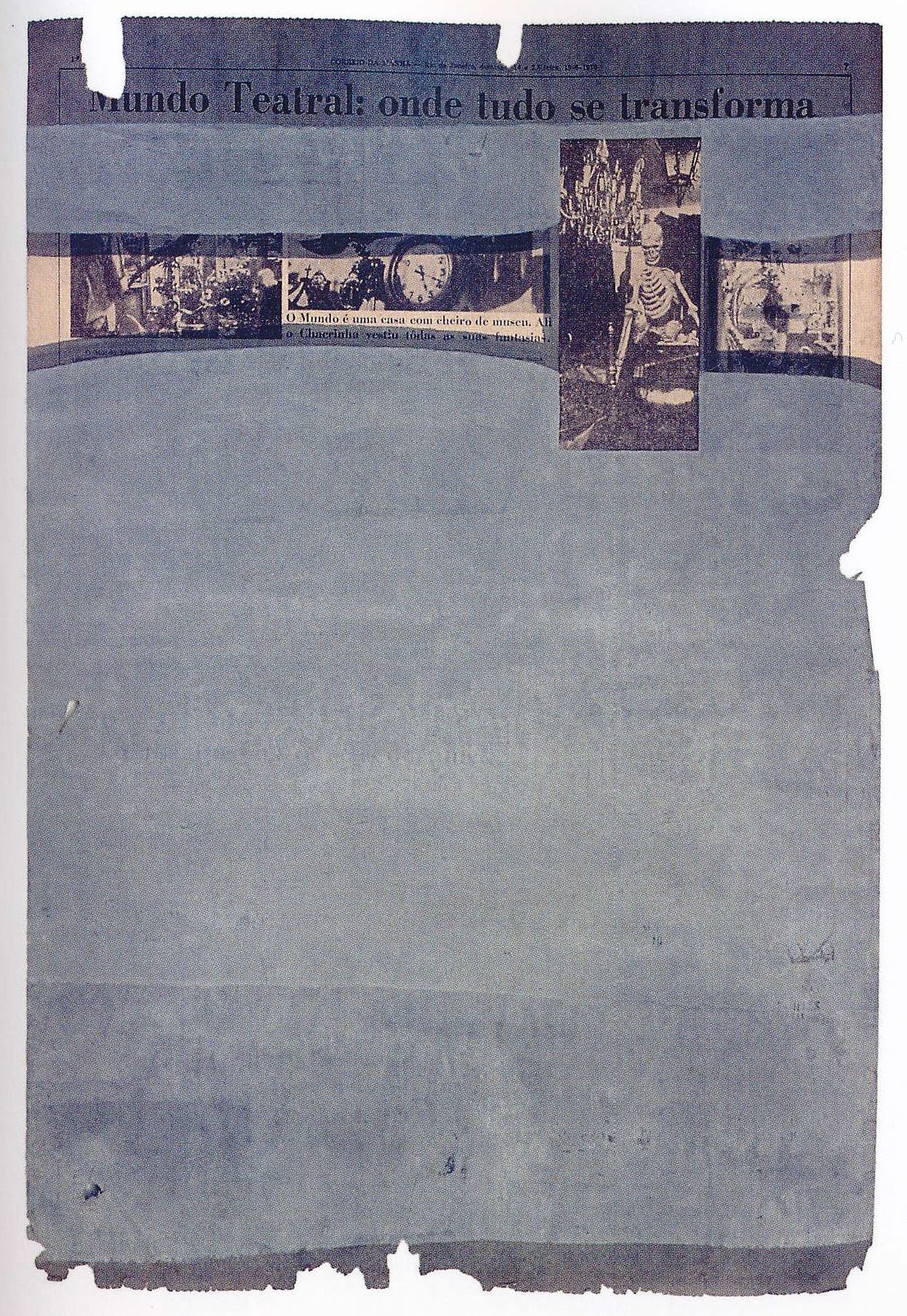

Brazilian artist Ana Vitória Mussi (b. 1943) also employed news in her series Jornais (Newspapers, 1970). News clippings are torn and painted over, and words and images are blocked out, ultimately telling new stories and creating alternative media narratives. The strictly informational purpose of the newspaper is negated here, and through the use of imagination and deconstruction a new medium is produced.

<figcaption> Ana Vitória Mussi, Mundo teatral (Theatrical world), from the series Jornais (Newspapers), 1970. Gouache and Ecoline on newspaper, 58 x 38 cm. Collection of Ana Vitória Mussi. © Hammer Museum 2019

Uruguay’s Nelbia Romero (b. 1938) was part of a culture of experimental artists and printmakers who used their own powerful methods of creating and distributing discourse against the regime under military dictatorship. Through text and art publications circulating in underground social “clubs” (most centrally Club de Grabado de Montevideo), resistance could be practiced discreetly and what would normally have been censored could be explored. Art activists like Romero now had means of sharing their work – even as art in the public domain was being banned and monitored. Romero makes use of printing ink in Sin título (Untitled, 1983). She photographs her face covered in a mask of inky dark sheen, nearly unrecognizable through the brushstroke of paint over her nose, mouth, and neck. In the lower left quadrant the number 01592 is printed in red, an unmistakable reference to the system of classifying Uruguayan detainees.

Freedom from authoritarianism begins with the realization of its existence and its structure. Social critique to deconstruct the paradigm that supports systemic violence, poverty, and racism upheld by the current political leaders of the US can happen in many unlikely ways. Art and other creative forms of protest have historically been used to counter censorship and document histories that are often forgotten, erased, or rewritten by those in power. In thinking about and discussing what a dystopia might look like today, or if we are in an unwritten version of one now, we can also imagine an alternative future: A global network that celebrates individualism, artistic expression, and critical analysis. Art provides a freedom similar to how dystopian fiction gives authors the space to express what they want about society. Three brilliant artists, through decades of fascism and civil war in Latin America, used their practices to negotiate new bonds between art, politics, and language.

Felix Jordan Rucker was born Rochester, MI, 1992 and lives in Detroit. She has a BFA from College for Creative Studies.

This text was initially published in the second C& Special Edition #Detroit and commissioned within the framework of the project “Show me your Shelves”, which is funded by and is part of the yearlong campaign “Wunderbar Together (“Deutschlandjahr USA”/The Year ofGerman-American Friendship) by the German Foreign Office. Read the full magazinhere.

Read more from

Rest in/as Freedom: kiarita and Black Politics of Liberation

Not for Sale: How Black and Indigenous artists are rewriting the rules of the art market

Sudan Art Archive Aims to Reclaim a Canon from Afar

Read more from

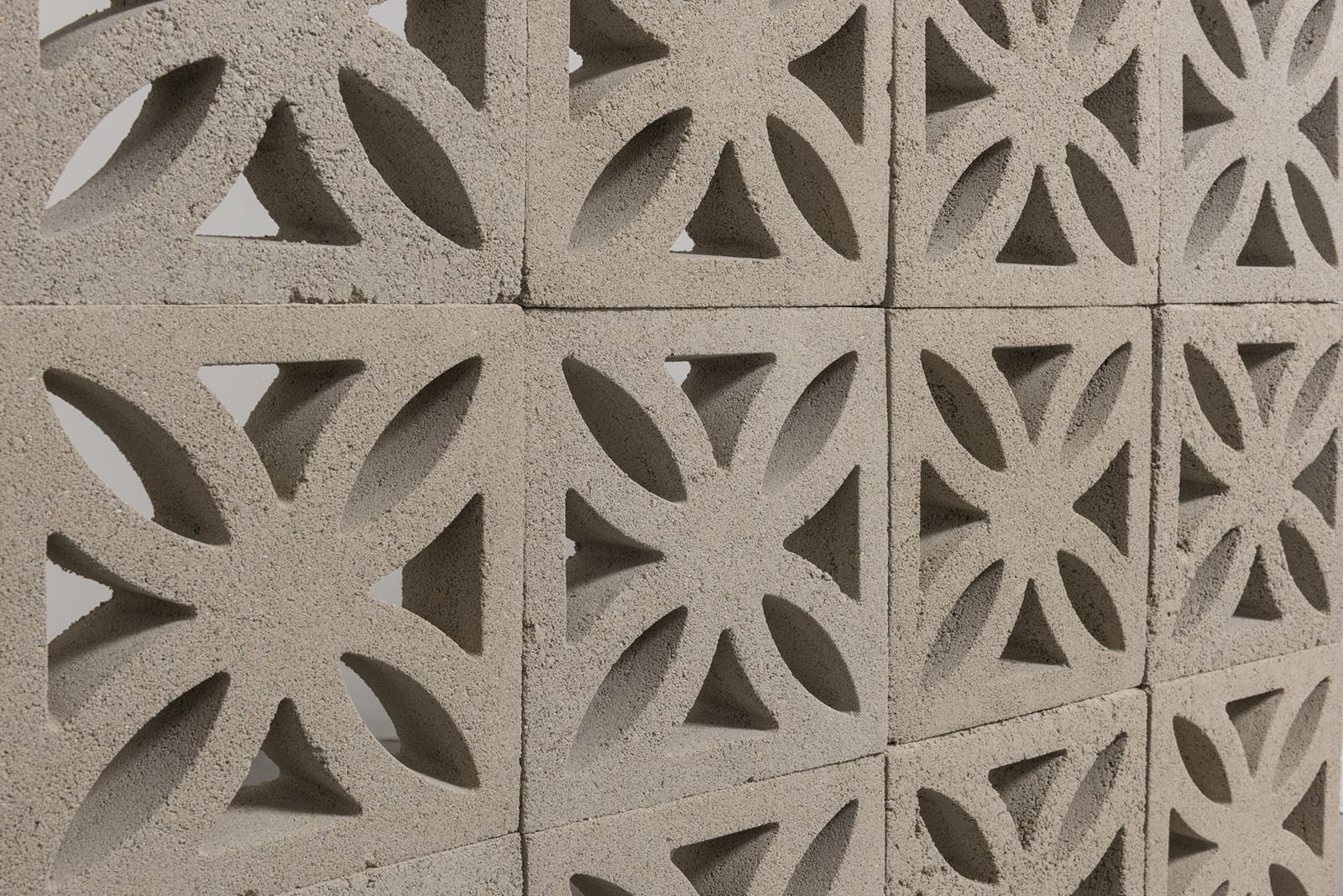

Mariana Ramos Ortiz: Sand as a Symbol of Structural Fragility

Art in Support of Political Change