Embracing Sustainable Practices and Attitudes in Times of Political Uncertainty

Participating artist and writer Annie-Marie Akussah shares her views on the Biennale of Photography.

Maa ka Maaya ka ca a yere kono is the title of the 13th edition of the Bamako Encounters – African Photography Biennial. The Bambara expression is taken from Aspects de la Civilisation Africaine, the 1972 book of Amadou Hampâté Bâ, and translates to English as the persons of the person are multiple in the person.

As quoted from Amadou Hampâté Bâ in the curatorial statement: “Tradition teaches that initially there is Maa, the Person-receptacle, then Maaya, i.e. the various aspects of Maa contained in the Maa-receptacle.”[1] This suggests that the position of person is always inhabited by/with multiple persons. This is the crux of the set of ideas that the biennial invites us to reflect on and embrace. Upholding our right of becoming and multiplicity is a position of resistance and emancipation for those who have been subjugated to a singular identity, demarcated and circumscribed by shores, choppy winds, and territorial myths. The subjugated who perversely re/poses in a cast which has been mutative all the while. This irreducibly singular mutative ability, which once was and continues to be a strategic egalitarian stance, presents itself like a point de capiton,[2] only to find its meaning and identity (de)stabilized by an encounter or perhaps another gust.

As one of the seventy-five participating artists, I found the central questions of multiplicity, difference, becoming, and heritage to form a befitting call to celebration, action, and a reflexive discourse necessary for the conditions and spaces we find ourselves in. To keep exhibitions of this kind alive we must embrace sustainable practices and attitudes towards the necessary infrastructure. Despite delays and the precarious political situation, our gathering, our contributions, and our zeal to honor one of the most significant Pan-African Art exhibitions speak to the value and importance of art during uncertain times in, for, and by our community. The inaugural week saw several interventions and workshops that activated the city, including film screenings at the Cinema of House of African Photography and the Archive Haptic Library, and a DJ set by Atiyyah Khan. In the name of art and culture, a solidarity emerged among the artists, curators, technicians, jurors, the press, and visitors to the biennial.

[cand-gallery image-no=3]

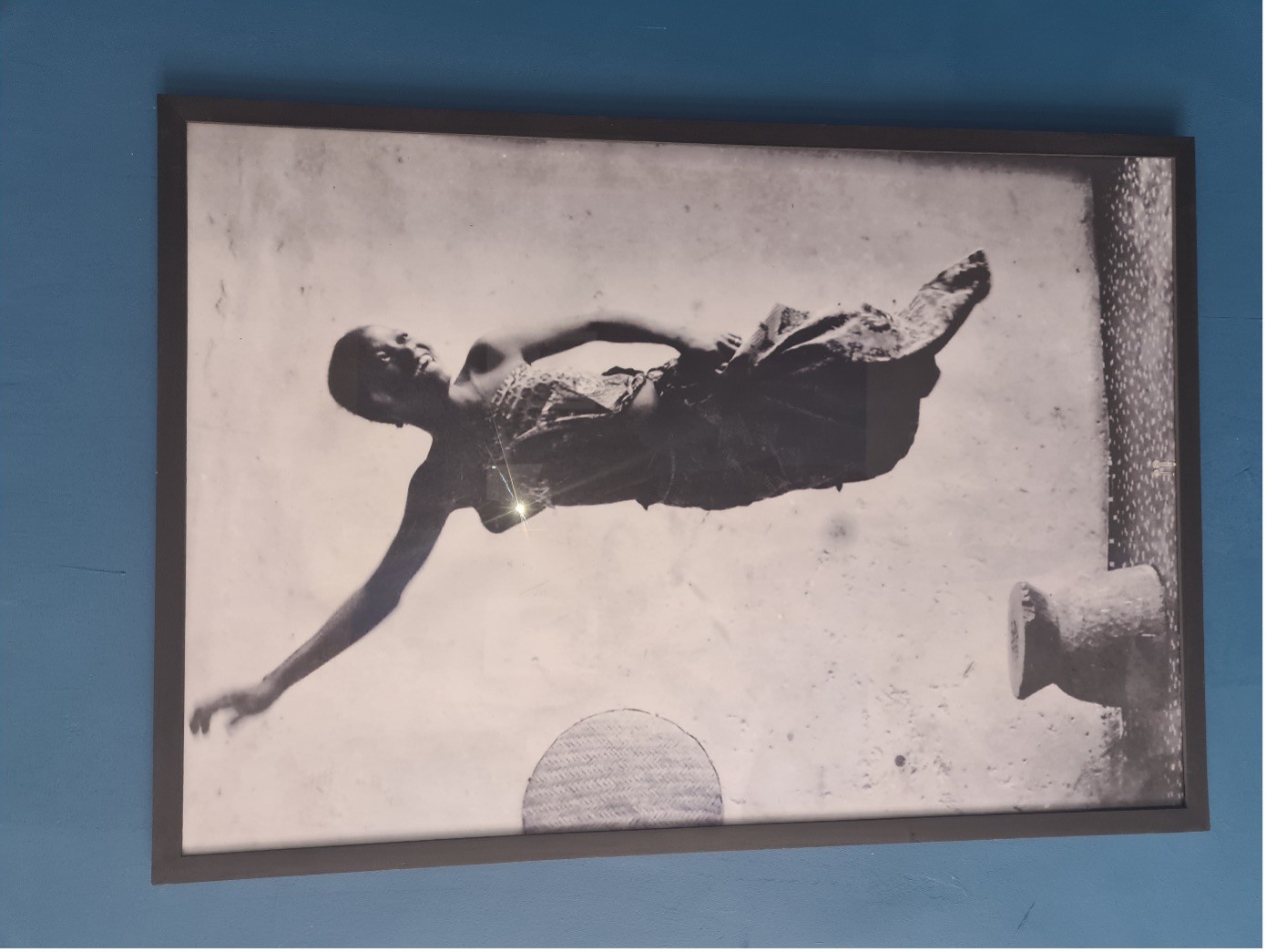

Spread across multiple sites, the exhibition unfolds in five chapters taken from Aimé Césaire’s poem “Défaire et refaire le soleil” (Unmaking and Remaking the Sun).[3] The first chapter, Dwelling made of not knowing which way to turn, is situated in the post-independence space of the National Museum of Mali. The works of the seventeen artists in this chapter together conceive a habitat of pulsation and movement, speaking to a discourse on land, placeness, and spaceness. A habitat of undoing and construction, of precipitation and fragments. The large disjointed images of a somersaulting man in Neville Starling’s work are a material showing of this becoming in being – of the inherent trace partaking in a dis/continuous flow. By way of revealing this infinity of beings and flows, a structural split occurs, transmitting a tautological bricolage. The redisposition of the somersaulting man suggests recognizable bodies and various temporalities of image-making, invitating us to remake new bodies and pairs while experiencing the work. The deep red pigment on the exhibition walls and architectural bridges that rest among the works overlap and connect to the landscape outside. They mimic the mount of earthy red soil in Binta Diaw’s installation of a large photographic image of a Black body laying and reaching into a red landscape.

Chapter two, Dwelling made of fan fingers, situated and activated in the historic vestige of the train station, fixates on multiplicities of identities, beings, and becomings. There are ten artists in this chapter. Through abstracted African landscapes comprising of satellite images and photographs of human skin and irises, Fairouz El Tom asks: “where does the ‘I’ end and the ‘You’ begin?”[4] The act of distinguishing and identifying the “I” from the “You” paradoxically affirms one’s own otherness from another consequently entwined and sharing in the same space of otherness. In this lens, fabricated moulds and borders are blurred; the human and non-human also blurred. Gherdai Hassel (re)presents an installation of archival images that have been reconstructed by editing, cutting, re-assembling, and re-imagining, by way of contemplating memories of the past to survive and be imagined in the future.

[cand-gallery image-no=4]

At the House of African Photography, where chapter three unfolds with two retrospectives of Joy Gregory and Daoud Aoulad-Syad, twenty-two artists present a rich dialogue on the living cultures, presences, and continuities of heritage. Dwelling made of mustard seeds is the title of this chapter. It brings together works that deal with the archival, with collective memories and his/herstories, personal connections and their contemporaneity. We participate in intimacy with the familiar through a game of memory in Adji Dieye’s 14-minute video Culture Lost and Learned by Heart, Memory, accessed through the body in Mallory Lowe Mpoka’s captivating hangings as a site of transformation. Mpoka’s hangings experimentally bring the presentation of photography into a discourse of painting and sculpture. Their bodies are stained with the red earth pigments of her familial landscape in Western Cameroon, with holes and gaps, and draping red cotton threads reaching for the ground and creating shadows. The body qua memory and a bearer of auras and marks. The body qua landscape. (Mpoka was the co-winner of the biennial’s Malick Sidibé Prize.)

[cand-gallery image-no=1]

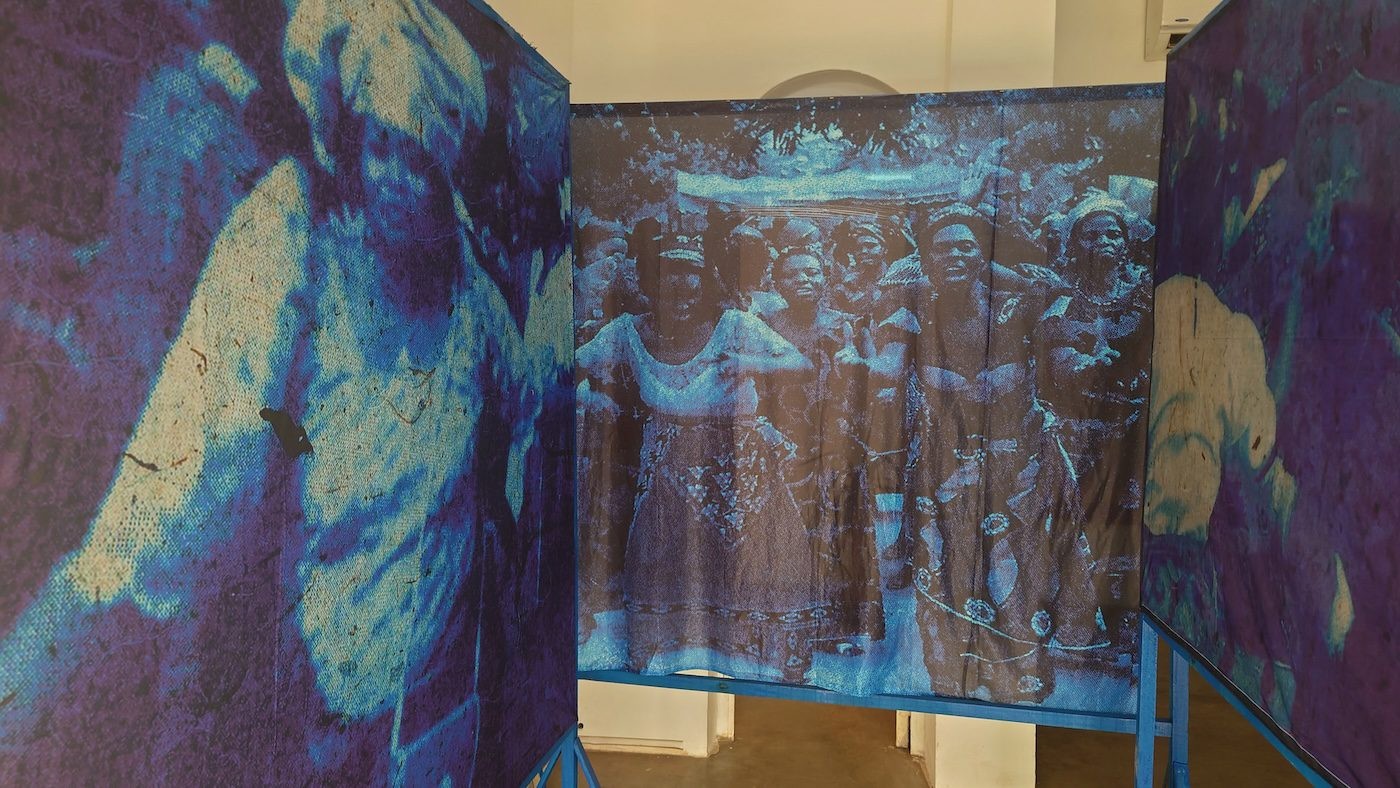

Chapter four, Dwelling made of fallen angel feathers, dealing with dispersals, connectedness, and the performativity of languages and histories, is sited at the Memorial Modibo Keita with twelve artists whose works explore movement and the complex phenomena birthed from it. The varied material textures in the exhibition reflect the crux of the biennial, its concern with the multiple possibilities of image-making. Nene Diallo uses wax-print fabric, scraps, and silver gelatin prints from her family’s archive; her assemblage of images referencing different times and sites, actively layers, contributes to, and complicates personal and collective histories. South African Artist Luvuyo Equiano Nyawose, contributes to the archive of Black social life by documenting Black people in a historically charged public space: these images capture celebratory and intimate moments within the ocean – which holds so much memory, which has witnessed the lived experience of Black bodies. As you look ahead, behind Luvuyo’s images, blue hangings float beneath the railings. These hangings that I have presented bear archival images, marks, drawings, and texts made of silkscreen meshes. The meshes which are typically secured in a frame to produce serigraphic prints are liberated and exhibited as they are, in two rooms. In this format, they act as an image-making machine with openings that birth new images with other bodies in the space. They are a material showing of multiplicity and difference, a difference in itself.[5] An(other) in itself.

[cand-gallery image-no=2]

So it is this same position of upholding one’s right of becoming and affirming the multiplicity of being that is a means of survival for many. For some, remaining in flux is a necessary tool to navigate in the world. Chapter five, Dwelling made of rainstorms of the deluge – Of flows, transitions and supranaturality, inhabits the District Museum. Here twelve artists pose several questions. Questions about the image, questions of fluidity, questions of the Congolese woman, questions between ourselves, questions of the deeper spiritual archives and of new geographical markings. The consistent dusky lighting in Baff Akoto’s film invites curiosity and contemplation: Leave the Edges is a beautiful exploration layered with multiple sites of ritual performance, with scenes of the Groupes à Po in the Guadeloupe Archipelago and dancers with their faces covered in shimmering gold markings. Its sonic atmosphere transitions through an evocative flamenco dance performed by a Yinka Esi Graves, through which in turn the ritual of dance becomes a bearer of histories, a site where peoples inherit and share knowledge. The 39-minute film installation is brilliantly composed with gentle moments and loci of participation; Jumoke Adeyanju also performs a text that is developed in the frame, existing in the fabric of the time of the film. We gaze at Jumoke as she composes, reflects, and interrogates in her process of constructing meaning. Thematically concerned with notions of plurality and cultural inheritance, Leave the Edges, which won the biennial’s Seydou Keita Grand Prize, evokes and meditates on the fluidity of cultural exchange.

The13th edition of the Bamako Encounters opened on 8 December 2022 and closes on 8 February 2023.

Annie-Marie Akussah is an artist, writer, and educator who lives and works between Kumasi and London. Prior to commencing her Masters in Painting and Sculpture at KNUST (Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology) in 2019, she lived, worked, and received her BFA in London at Wimbledon College of Art (University of the arts London).

Find some installation viewshere.[1] Translated from the French by Susan B Hunt in the curatorial statement, which can be found here: https://www.rencontres-bamako.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Concept-UK.pdf.[2] The French term point de capiton is taken from Jacques Lacan’s work to describe an illusion of fixed meaning in the signifying chain.[3] Originally published in the 1940s, translated into English by A. James Arnold and Clayton Eshleman in Solar Throat Slashed: The Unexpurgated 1948 Edition (Wesleyan University Press, 2011).[4] This quote is taken from artist statement.[5] Gilles Deleuze explores the idea of difference in itself in his book Difference and Repetition, originally published in 1968.

Performance art

Filipa Bossuet: Performance as Conversation, Intimacy as Power

Sarah Ama Duah: A Journey Towards Building Contemporary Monuments

Anaïs Cheleux: Connecting Caribbean Identity Through Photography and Performance

Bamako

The Resilient Spirit of the Bamako Biennale

Rencontres de Bamako 14 Reveals Artist List for 2024