Disrupting the Archives with Renée Akitelek Mboya

Archives are complicated. Never neutral, they carry the imprint of those who organize their catalogues, making choices about what to include and what to omit. They often falsely promise to hold comprehensive views of history. Nairobi-based curator and filmmaker Renée Akitelek Mboya will spend the next three months in Berlin investigating archives in search of …

Archives are complicated. Never neutral, they carry the imprint of those who organize their catalogues, making choices about what to include and what to omit. They often falsely promise to hold comprehensive views of history. Nairobi-based curator and filmmaker Renée Akitelek Mboya will spend the next three months in Berlin investigating archives in search of a student protest that took place in 1966 in what was then West Berlin. She is participating in the TURN2 Residency program funded by Germany’s Bundeskulturstiftung.

C&: You’ve said, in different contexts, that the written word, or language in general, can be insufficient. Could you elaborate on how this thought affects your curatorial approach?

Renée Akitelek Mboya: I don’t know if I think the written word is insufficient or if I simply want more. The difference between “enough” and “abundant” is vast and I think we should be able to have it all, and then a lot more. Language, yes, but also sound, light, taste, texture, vibrations from the depths of the earth, maybe a little bit of time travel. Through all of these one can encounter and engage with culture, which is how I also learnt about my own cultures. In my understanding the curatorial is a way of creating encounters that disrupt the status quo – the place we all inhabit and yet find to be antagonistic to a good life. I spent many years negotiating my humanity in art spaces and now I insist on engaging only with places and contexts in which I can be truly visible and where I can bring in my people – the living, the ancestors, and the descendants, my whole community. Unfortunately language is often burdened by hierarchies, not of our choosing. I have less anxiety around being illegible or illiterate than I do about speaking over people or speaking out of turn.

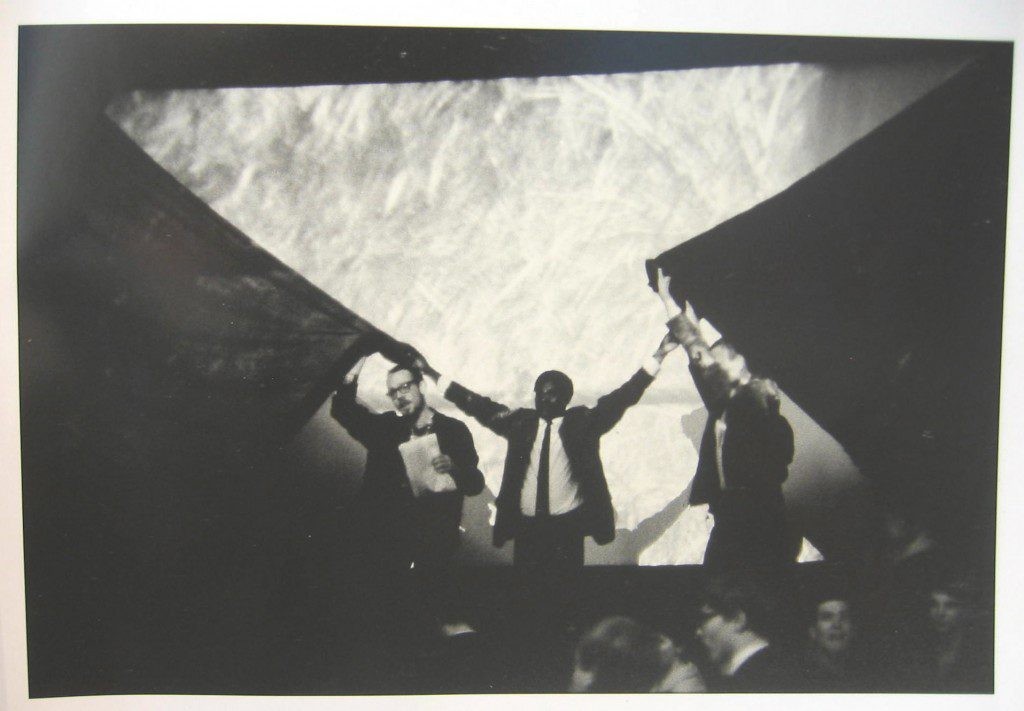

C&: In 1966 a group of African students who were studying in Germany protested the screening of a highly problematic Italian film called Africa Addio, which employs colonial and racist imagery and ideology. What role does the moving image in general play in your practice?

RAM: The protests that took place outside the Astor Cinema on Kurfürstendamm in 1966 were fundamental to the articulation of Black consciousness in Western Europe at the time. In tandem African student organizations in Germany – both in West Germany and the GDR – found a surprising amount of political freedom with which to speak against injustices playing out in their home countries. I’m specifically thinking about the Biafran Club and the Kenyan Student Union. The images from these protests are powerful that they represent the geokinetic possibility of revolt, and I think that they speak to the agency that we may have to do the same in our world now.

I don’t think I need to give any more attention to the hype around Africa Addio. It is a racist and violent film, but it is very much in keeping with the prescriptions of white supremacist film culture. It’s not unique by any means and it’s not a particularly “good” film. I choose to not see myself in that way, but ultimately a camera is a powerful thing and as someone who is often looking through the viewfinder I have to take responsibility for my perspective and my own potential to reproduce and disseminate violence. In my practice, I aspire to encounter these images and reorder (or curate) them in a way that interferes with their violent potential.

C&: Your project sounds like a multilayered diasporic undertaking. As a person coming from Kenya, a predominantly Black nation, does the experience of Diaspora have different connotations for you than for a Black person from a Western country?

RAM: I can’t speak directly of the experience of Black Diasporas in Germany or any diasporas for that matter but I do know what it is to be displaced. I know the feeling of exile and what it means to always be negotiating questions of home. I come from a Black nation, yes, but I think even there we are still trying to figure out what is entailed in the question of nationhood. We are not hegemonous by any meand and we are still grappling with the loss of life, land, and language over the past few centuries. As a result, I understand Diaspora first as a place of empathy and solidarity.

C&: Any German archive with relevant material – be it print or footage – confronts us with the white gaze, particularly when it comes to authorship. But archival research is one component of your work here in Berlin. How can this material be useful?

RAM: I very much intend to gaze back – this is a confrontation I am prepared for. I think the privilege of being a guest in this space is that I can afford to be impolite in my process in ways that would not be possible if I was from here or if I lived here. I don’t owe these archives or their authors grace, in the same way that they don’t treat me or my likeness with kindness. My practice is one that (humbly) seeks to disrupt these archives; to subordinate them and to make them visible in ways that are comfortable to me; to put them into conversation with archives from the heritages they disrupted. This material is ‘useful’ to me because it helps me to understand how I came to be who I am and why there are fissures in my identity.

C&: What are your biggest hopes for these coming three months?

RAM: The US-American activist Mariame Kaba speaks of hope as a discipline, something we have to practice every day. While I am always hopeful, I think in this instance I am more curious about what a sustained encounter with this landscape, over the next three months, can do for the methods I have chosen to interact with the peoples and histories that have guided me here. In that respect, I take advice and rest my hope entirely in the African students who gathered outside the Astor Cinema in August 1966. I hope that they had – and are having – good lives. I hope they found joy. I hope that the next time they stood in front of a cinema it was to see Black bodies rendered beautifully. I hope that their hope wasn’t thwarted by that violent encounter with the state.

I suppose in some ways the practice of digging through the archives is always hopeful. One hopes to find something exalted in the mess of history, or at the very least find a point of repair. We’re here to make amends.

Magnus Elias Rosengarten is a writer and artist who currently lives in Berlin.

The TURN2 RESIDENCIES are a joint project of the Kulturstiftung des Bundes (German Federal Cultural Foundation), the ZK/U – Centre for the Arts and Urbanistics and the Triangle Network, in collaboration with the Bag Factory in Johannesburg, the Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute (NCAI) in Nairobi and the G.A.S. Foundation in Lagos. Funded by the TURN2 programme of the Kulturstiftung des Bundes (German Federal Cultural Foundation). Funded by the Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien (Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media).

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas