Multidimensional Narratives

The experience of visiting Black Chronicles II is one of being constantly pulled and pushed between the present and the past: what you may have already known and perceived to be a truth and what you perceive with your eyes in that moment. The ability of photography to aid and disrupt that process is …

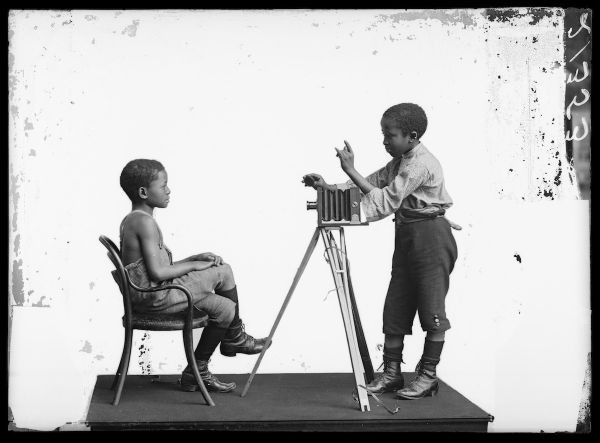

The experience of visiting Black Chronicles II is one of being constantly pulled and pushed between the present and the past: what you may have already known and perceived to be a truth and what you perceive with your eyes in that moment. The ability of photography to aid and disrupt that process is not to be underestimated. The exhibition begins in the ground-level exhibition space at Rivington Place in London and as you walk through the first set of doors, your eye is drawn into the gallery by the words of Stuart Hall that dominate the space and encircle the upper section of the room. The installation of 60 silver gelatin hand-prints is slick and authoritative with large-scale prints produced especially for the exhibition mounted in standardized black wooden frames on black walls. The impression is of a history worth telling and worth telling well. The men and women represented in the images, dressed in the finery and fashions of the day, take up their place in our imaginary of Victorian Britain.

One of the most striking encounters in this room is the series of portrait photographs of The African Choir who toured Britain between 1891 and ’93. The original glass plates, unearthed by the curator’s careful research, were found in remarkable condition at the Hulton Archive and had been unseen for 120 years. Standing in front of the images of The African Choir depicting elegantly dressed, sensitively portrayed men and women of African descent in Victorian London, it was a revelation to behold this hidden past and yet there was something of these perfect reproductions that added a layer of disbelief. The sitters are so present and recognizable in the faces of contemporary London that they almost appear as actors in elaborately dressed 19th century settings. This poses two related questions. Firstly, how much of that perception is testament to the insidious strength and violent subtlety of dominant narratives of history? Secondly, what can be attributed to the complex relationship between the reproducibility of the photograph image and its ability to transcend time? The questions remain to be untangled.

The history of studio portraiture and the black subject presents a vast, multivalent narrative spanning Africa and its many Diasporas. Yet whilst knowledge of 19th and early 20th century photography on the continent of Africa has moved forward with the publication of key anthologies such as Revue Noir’s Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography (1998), the recent Portraiture & photography in Africa (2013), and many more publications in between, portraiture of the black experience in Britain of this period is considerably less known. Black Chronicles II stands as a reminder of the fact that both are deeply connected, sharing a history that spans spaces beyond these shores and time far before the Second World War.

Where Hall’s words may have felt like a graphical distraction from the simplicity and strength of the hang in the ground floor gallery, in the upper gallery the audio that played out his keynote speech from Autograph ABP’s inaugural archive symposium The Missing Chapter: Cultural Identity and the Photographic Archive was captivating and I, like many visitors, stayed back in the room to hear it in its entirety. In this gallery space, intimate clusters of original carte-de-visite cards from a number of private collections are presented alongside a slide projection of studio portraits of the King’s Orderly Indian Officers (1903–38) from the National Army museum and Effnik 1996 by British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare MBE.

The scale of the cartes-de-visite commanded close inspection and once due respects were paid to the first number, I found it essential to stop and contemplate each and every person presented there. In return I came across an image of Prince Alamayou, son of King Theodore II of Abyssinia. Orphaned after the British invasion of Ethiopia in 1868, he was brought to England and made a personal acquaintance with Queen Victoria. The young man’s fate is now scattered across Britain’s great institutions, a reappearing figure whose items of clothing I had seen in a collection display at the Victoria and Albert Museum under the title Africa: Exploring Hidden Histories (15 November 2012–3 February 2013). I also encountered Millie and Christine McKoy, “The Two-Headed Nightingale,” conjoined twins who were born into slavery in America in 1851 and toured the United States and England as entertainers, performing for the Queen in 1871. The McCoy twins also became a reference for one of the sixty prints in DeLuxe, 2004–5, the ambitious multilayered print work by American artist Ellen Gallagher.

Black Chronicles II is a testament not only to the black experiences in Britain but also the interconnectedness of that experience with Africa and its diverse Diasporas. The exhibition evidences the presence of people of African descent all across the United Kingdom. It presents a multidimensional narrative of the both tragic and complex stories of people like Prince Alamayou who, despite being favored by the Queen, has been written out of mainstream history. It also celebrates a mobile, cosmopolitan Diaspora participating in Victorian life with a dignity and agency.

Hansi Momodu-Gordon is a curator, writer and producer. She is assistant curator at the Tate Modern where she works on exhibitions, commissions, and collection research.

Black Chronicles II: 12 September–29 November 2014

Rivington Place, London EC2A 3BA, UK

Hansi Momodu-Gordon is an independent curator, writer, and producer with recent projects at Autograph ABP and The Showroom (2015), and her book of artist interviews 9 Weeks is published by Stevenson (2016). She has held curatorial positions at the Tate Modern (2011-15), Turner Contemporary (2009-11), and the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (2008-09), and published writing on contemporary art with The Walther Collection, Rencontres de Bamako 10th edition, Frieze, and elsewhere.

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission