In the post-war period, many pioneering Black artists were largely neglected by the Western art world despite their significant contributions, and persevered regardless. In the last ten years Western institutions have been waking up to these artists’ legacies. They are finally curating first retrospectives – and of course the markets have followed suit. In this series we chart their careers, highlighting their artistic evolutions and motivations in relation to the world around them. Betye Saar politicized the female Black body in her assemblages and collages decades ago. And as part of the Black Arts Movement in the 1970s, Betye Saar negotiated limited perceptions of race and femininity. Two US exhibitions, one in New York, the other in Los Angeles, currently pay tribute her outstanding work.

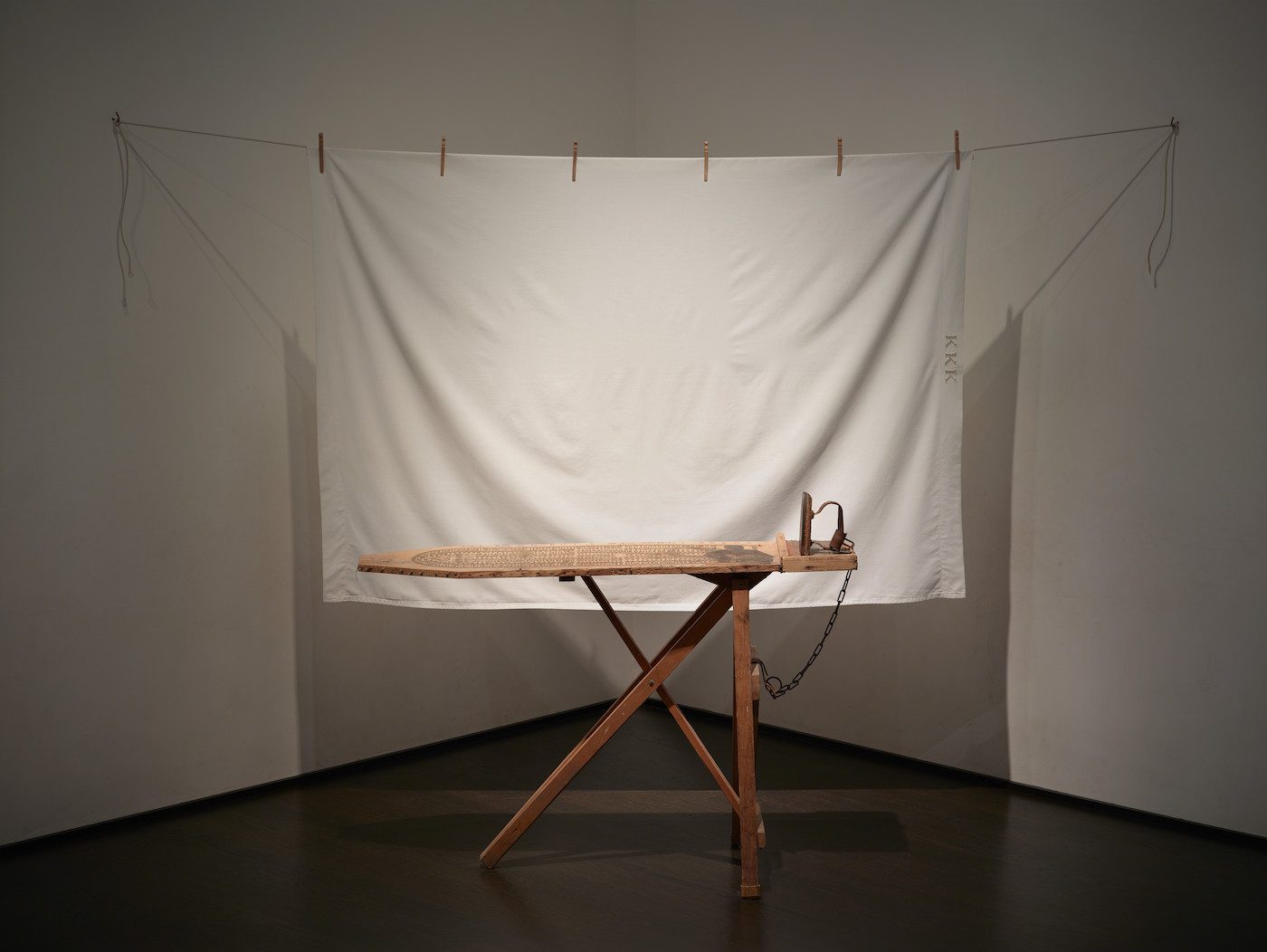

Betye Saar, I’ll Bend But I Will Not Break, 1998. Mixed media tableau: vintage ironing board, flat iron, metal chin, white bed sheet, six wooden clothespins, cotton, clothesline and one rope hook, 80 x 96 x 36 in (203.2 x 243.8 x 91.4 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Lynda and Stewart Resnick through the 2018 Collectors Committee, © Betye Saar

Perhaps the magic that Betye Saar imbues into her artworks has something to do with a majesty she has within her hands. She sources pieces of wonder in flea markets, bazaars, and family heirloom collections, carefully seeking out those that have the right kind of “mystery” or proportion to fit into her assemblages and collage.

Betye Saar, Supreme Quality, 1998. Mixed media on vintage washboard and tub, 37.5 x 22.25 x 20 in (95.2 x 56.5 x 50.8 cm), Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California

Featured prominently in Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963–1983 (2017–19), with works like The Liberation of Aunt Jemima from 1972 (also shown in WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution(2007–08), curated by Cornelia Butler), Saar is having somewhat of a moment. The Liberation of Aunt Jemimain particular is timely, given the rhetoric around US gun violence and the mainstream complacency around matters of racism, anti-immigration, and US-grown terror acts. Now ninety-three, Saar has witnessed a long history of such phenomena, and more. Her art took a more political arc after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, and has not stopped since.

Betye Saar, Sketchbook, 2009–2010, 2009–2010, Overall: 5 1/2 x 4 in.; Sheet: 5 x 3 1/2 in., Collection of Betye Saar, courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, © Betye Saar, photo © Museum Associates/ LACMA

The title of the touring exhibition now at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Betye Saar: Call and Response,references the West African form of interaction between two groups in prayer or song where one group responds directly to the other’s voice. This form of interaction is one often seen in churches across the US and in folk traditions. In this case Saar’s works respond to her collection of sketchbooks, which outline an idea or problem and call for an explicatory vision – which she always fulfills. This is the first time her sketchbooks have been exhibited and it’s a wonder that artists are so rarely asked to show their thoughts in this way. Sketchbooks often contain the first rumination of an idea, they may recall phone calls, conversations, sketches, or fabrics swatches. They give us a window into process, helping build a clearer vision of how artists create.

Her 1998 installation I’ll Bend But I Will Not Break is incendiary. An ironing board engraved with the infamous depiction of the cruel and violent arrangement of African bodies forcibly moved from the continent to the Americas (the 1788 rendering of the Brookes ship), along with a chained iron and outstretched white cotton hanging proudly over rope, is a horrifying visual proclamation of an America that has never answered to its violent past. In Saar’s sketchbook partnered with this installation, we notice that an invisible Black woman would have been laundering the perfect white sheet in which the owner would have subsequently attended his Ku Klux Klan rally.

Betye Saar, A Loss of Innocence, 1998. Mixed media installation, 50 x 12 x 12 in (127.0 x 30.5 x 30.5 cm), Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California

Likewise from the same year, the installation A Loss of Innocence puts us in the place of a young Black girl encountering racist slurs that some still encounter today, maybe through different means – through condescension, or assumptions about wealth or lack thereof. Saar used the conceit of a vintage lace dress that might be worn for a christening or baptism, and hand embroidered onto it phrases like “nigger baby,” “coon,” and “tar baby.” From afar the sweet-looking dress hangs from the ceiling over a small framed image of a Black child, casting haunting shadows onto the wall. There are these moments throughout the exhibition where you want to cry into your sleeve and thank artists like Betye Saar for their courage to create such work and give voice to feelings that otherwise lie dormant in our bodies for decades.

Betye Saar. Black Girl’s Window. 1969. Wooden window frame with paint, cut-and-pasted printed and painted papers, daguerreotype, lenticular print, and plastic figurine, 35 3/4 × 18 × 1 1/2″ (90.8 × 45.7 × 3.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Candace King Weir through The Modern Women’s Fund, and Committee on Painting and Sculpture Funds. © 2019 Betye Saar, courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles. Digital Image © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Photo by Rob Gerhardt

More moments like these will soon occur in New York at the Museum of Modern Art, hosting more of Betye Saar later in October. The Legends of Black Girl’s Window, organized by Christophe Cherix and Esther Adler, is an in-depth solo exhibition exploring the deep ties between the artist’s iconic autobiographical assemblage Black Girl’s Window (1969) and her rare prints from the 1960s. This is a revisiting, some fifty years on – a look into Saar’s early print-making and a response to a vision of her younger self – a rambling, questioning, dreaming self. I wonder what that self might conjure up today with the political shenanigans in the White House and the press’s rarely impartial reporting. I wonder what mystical, ethereal musings the young Saar might muster with her inks and tiny sketches.

Betye Saar: Call and Response, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. On view from September 22, 2019 through April 5 2020.

Betye Saar: The Legends of Black Girl’s Window, NY MoMA. On view from October 21, 2019, through January 4, 2020.

Nan Collymore writes, programs art events and makes brass ornaments in Berkeley California. Born in London, she lives in the United States since 2006.

This text was commissioned within the framework of the project “Show me your Shelves”, which is funded by and is part of the yearlong campaign “Wunderbar Together (“Deutschlandjahr USA”/The Year of German-American Friendship) by the German Foreign Office.

INVENTING YOUR OWN GAME

More Editorial