C& talks to young photographer Namsa Leuba

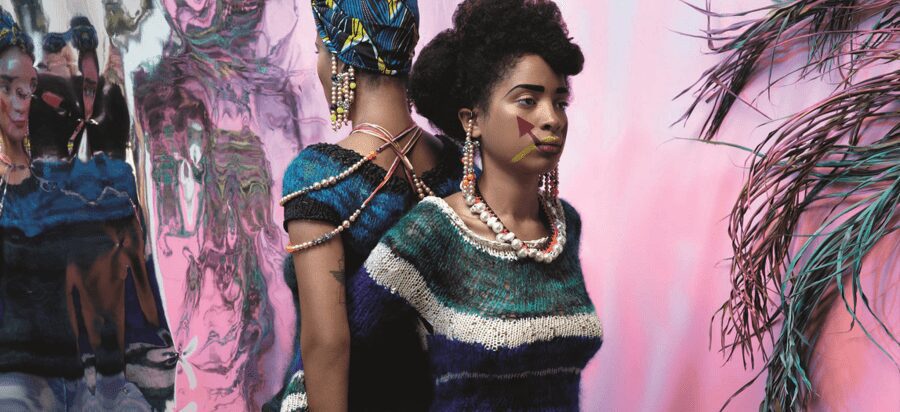

Namsa Leuba, Untitled V, The African Queens, 2012. Fibre pigment print. Courtesy of the artist and Echo Art

C&: What made you choose photography as a medium?

Namsa Leuba: Before I studied Photography and for my Master in Art Direction at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, I did Information Design during which, in my second year, I had a photography class. At that moment I felt in total harmony with the medium and knew I wanted to get better at it. A picture sometimes speaks much more than a thousand words.

C&: How did the Zulu Kids and Ya Kala Ben series come about?

NL: Both series were inspired by statuettes. My Guinean mother is Muslim and animist, and my Swiss father is Protestant, although I’ve not been baptized. I became very interested in the religious aspect of my mother’s country. I discovered an animistic side to Guinean culture and I was exposed to the supernatural side in Guinea when I was a child. I visited “marabouts” (a kind of witch) when I was younger and for Ya kala Ben (2011), I took part in many ceremonies and rituals. For me it was important to do this work, because I feel more aware of the existence of a parallel world, and the world of spirits.

The series Zulu kids was produced during my residency in South Africa in 2014 with Pro Helvetia, the Swiss Art Council. Following Ya kala Ben, which explored rituals common to the cosmogony of Guinea, I continued my research into indigenous cultural practices in Africa. Working with the communities of the Khoi San, Zulu, and Lesotho ethnic groups in South Africa, I staged photographs that juxtapose characters with landscapes and traditions from the local environment. I try to acknowledge my position as both an insider and outsider – my works toes that line to portray African culture as both fantastic (from the outside) and contemporary.

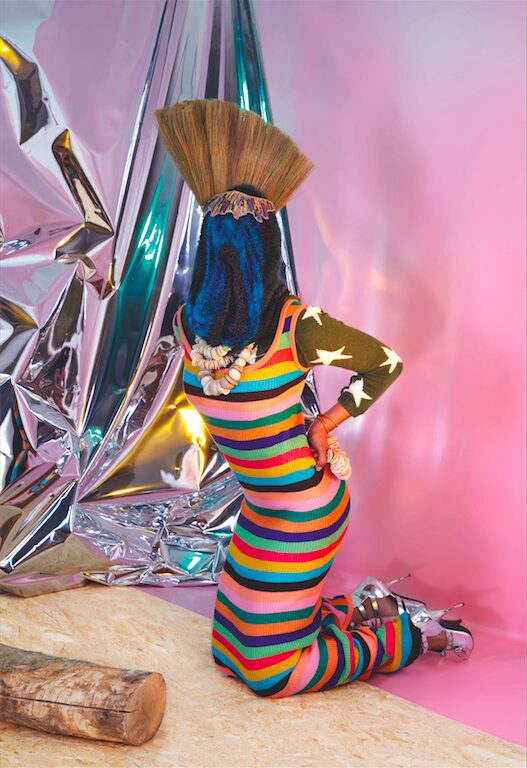

Namsa Leuba, Patience, from the series Zulu Kids, 2014. Fibre pigment print. Courtesy of the artist and Echo Art

C&: The images in your series Ya Kala Ben are beautiful aesthetic pieces, yet they maintain a cultural richness for viewers to appreciate. You have said, “I sought to touch the untouchable” in this series. To what extent did you achieve this?

NL: I was interested in the construction and deconstruction of the body, as well as the depiction of the invisible. I travelled through Guinea and observed different rituals and ceremonies to find the ones I wanted to create the series from. The statuettes I looked at are ritual artefacts common to Guinean ceremonies; they represent another world. They are the roots of the living. In this way, I sought to touch the untouchable. Photography allows me to exteriorize my emotions and my past, telling my story through different shots, in some kind of syncretism.

Namsa Leuba, Untitled IV, from the series The African Queens, 2012, Fibre pigment print. Courtesy of the artist and Echo Art

C&: What kind of stories about African and diasporic identities do you want to tell through your portraits?

NL: My work focuses on African identity through Western eyes. I am interested in African cosmogony in order to start a dialogue with my origins.

.

Interview by Aïcha Diallo

More Editorial