Our author Gauthier Lesturgie took a closer at the retrospective exhibition dedicated to legendary studio portraitist Seydou Keïta

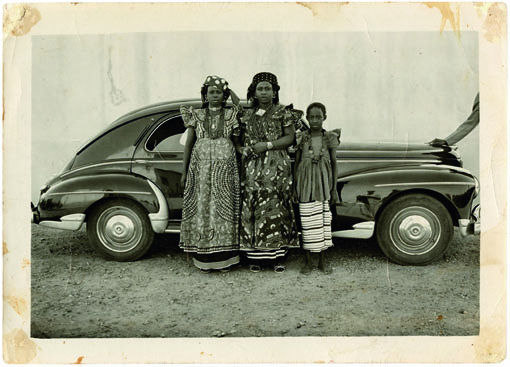

Seydou Keïta. Untitled, 1954. Silver print. Contemporary African Art Collection © Seydou Keïta / SKPEAC / photo courtesy CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva

In 1991 in New York, André Magnin visits the exhibition Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art at the Museum for African Art. He is struck by two photographic portraits by an anonymous artist from Bamako, and decides to go to Mali to look for him. Once there the photographer Malick Sidibé quickly identifies the photos of his erstwhile mentor: Seydou Keïta.

At the time, Magnin was working for the collector Jean Pigozzi and was putting together a collection with him dedicated to contemporary African art: the Contemporary African Art Collection. In 1994, Pigozzi organized the first solo exhibition of Keïta’s photographs at the Fondation Cartier in Paris.

The story of Keïta’s work tells us about certain plans that were in motion to create an African-oriented art market. The retrospective exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris provides us with an opportunity to view these works and to get away for a moment from the stories that are consistently appended as subtitles to them.

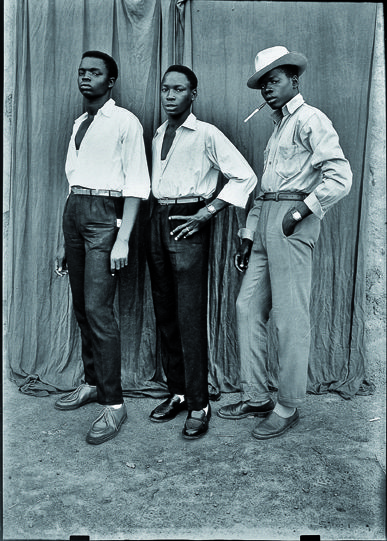

Seydou Keïta. Untitled, 1959 (Autoportrait). Silver print made in 1994 under the supervision of Seydou Keïta et signed by him. Contemporary African Art Collection © Seydou Keïta / SKPEAC / photo courtesy CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva

Seydou Keïta was born in 1921 in Bamako, the then capital of French Sudan. In 1935 his uncle returned from Senegal with a camera, which he gave to his nephew: it was a Kodak Brownie. The young man explored the medium with the help of Mountaga Kouyaté, who taught him the rudiments of photography. In 1948 he opened his own studio in Bamako. It was an immediate success. He played a part in the growing desire for representation among the middle classes, whose ranks were also swelling as a direct consequence of the industrial boom that followed World War II.

On September 22, 1960, French Sudan gained its independence and became the Republic of Mali. Modibo Keïta was elected president. Two years later, Seydou Keïta, who was enjoying considerable commercial success, was promoted to the post of official government photographer, at which point he closed his studio. We have almost no photographs from the period that followed this closure up until Keïta’s retirement in 1977 and subsequent death in 2001.

Seydou Keïta. Untitled, 1956. Silver print made in 1995 under the supervision of Seydou Keïta et signed by him. Contemporary African Art Collection © Seydou Keïta / SKPEAC / photo courtesy CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva

The exhibition starts off with some large “modern” prints that apply contemporary exhibition standards; thereafter, we find period prints presented in display cabinets in a circular room. Here we see an interesting shift in status in the photographer’s work as it moves between two poles: from pieces conceived for the satisfaction of a certain clientele to “works of art” to be put on display. Although he was retired, the photographer suddenly became an “artist”—again according to the modern “Western” definition of the term—and was to play an essential role in constructing his own mythology. Significantly, he started signing his work in the early 1990s.

Faced with a mosaic of photographs, located at the midpoint of the route through the exhibition, one visitor exclaimed, “The characters and costumes are superb!” A surprising comment to make in front of a series of portraits of thoroughly “real” individuals. However, these individuals have very studied postures and are using different narrative props and accessories in simulated situations, which gives them the appearance of characters to whom we can immediately assign roles: the soldier, the young dandy on his Vespa, the intellectual, etc.

Seydou Keïta. Untitled, 1952-56. Silver print. Contemporary African Art Collection © Seydou Keïta / SKPEAC / photo courtesy CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva

Keïta took most of his photographs in natural light in the inner courtyard of his house. He made various items available to his clients: objects, clothes, and backdrops, so that each picture could be dramatized with a personal flair. From the outset, the almost systematic use of fabric backdrops creates a setting that immediately gets away from a mundane situation or evades the attempt at illusion.

These portraits reveal to us something about the fantasies of Bamako’s middle class in the 1950s and 1960s: from the props and accessories that are selected through to the postures and poses, one finds in them an astonishing collection of constructed and predictable attitudes for each age group, of genres, professions, and roles assumed within the family. We discover authentic choreographies where the positions in space, the gestures, or the looks we encounter give a clear account of the relationships between the characters.

On the eve of independence, the photo studio thus freed itself from the anthropometric mode of photography that had been used by the colonists since the end of the 1840s to classify the people they colonized and to document these “unknown” territories, by shifting the question of who is representing who. Studio portraits made it possible for clients to lay claim to their own image to the point of disguising and recasting it.

The photo studios that flourished in the continent’s cities would gradually give ground as certain photographers went out on the street. This trend would open photography up to a narrative field more concentrated than that of the studio, where the very act of taking a photo corresponded per se to the event that was photographed. The photographic desire would thus escape from the manufactured world of the studio in order to invest in the ordinary. These changes coincided, needless to say, with the technological advances that the camera underwent. All the same, it is interesting to note this shift at the moment of independence, as if the public space could finally play its part in the desire for representation.

The (re)discovery of Keïta’s work is thus absolutely essential—this is true on the multiple levels that accompany the evolutions his work went through, a series of developments that this retrospective once again shared. Symptomatic of the dynamics of a market in a state of constant transformation and with real importance in analyzing the history of photography and Bamako’s society, these portraits make an irreversible break with their original status, their commercial nature, and the private sphere.

Seydou Keïta, March 31 – July 11, 2016, Grand Palais, Paris

Gauthier Lesturgie is an independent art writer and translator (English to French) based in Berlin. Since 2010, he worked with several contemporary art projects such as Den Frie Centre for Contemporary Art (Copenhagen), 2nd and 3rd Rennes Contemporary Art Biennal or SAVVY Contemporary (Berlin). He is regularly writing for contemporary art journals such as Sleek (Berlin), Contemporary And (Berlin), Espace art actuel (Montreal), Inter art actuel (Quebec), Momus (Toronto), Mouvement (Paris), etc media (Montreal) or 02 (Nantes).

More Editorial