Meeting the artist Meschac Gaba at his home in Rotterdam.

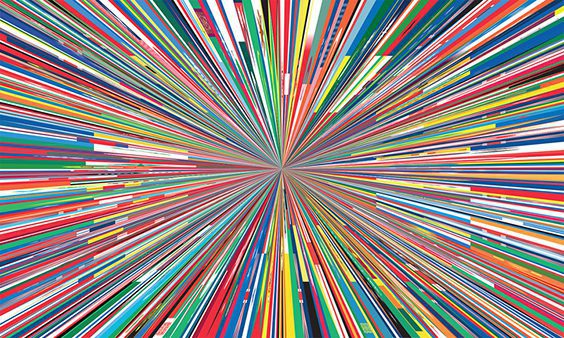

Meschac Gaba, Citoyen du Monde, 2012. © M.Gaba

Rotterdam may not be the most beautiful city in the Netherlands. But it welcomes you as the country’s architectural capital. It’s around noon on Saturday, and tourists stream relaxedly out of the city’s recently inaugurated central railway station. After walking a few yards, they turn around and take pictures of the eccentric entrance area that slants up like a giant metal splinter.

Meschac Gaba lives just a few minutes by taxi from the station. In the neighborhood, nice bars stand next to dog parlors and bicycle stores, and there are reduced, dark-red-brick family houses in the side streets. “I would have loved to be an architect,” says the artist, who was born in 1961, with a laugh as he sits down on the large sofa in his living room. But if he had he might prefer to build in Cotonou, the economic capital of Benin, where he spends at least six months of every year. His studio in Cotonou is not far from the airport, and has enough room to accommodate his installations, his art library, and a guesthouse for artists. Since the late nineties, Meschac Gaba has investigated constructs of cultural identity. Inspired by his own reality between the Netherlands and his native country Benin in West Africa, his work playfully explores various relationships—between Africa and the West, the local and the global, art and everyday life. He translates themes such as globalization, capitalism, ecology, migration, religion, and power into a visual language that is jolting without being shocking, that brings people together without cloaking them in social romanticism. In Rotterdam, he lives with his wife and their two children in a lightflooded apartment, in which he also works. “But most of my production occurs in my studio in Cotonou,” he says. “The climate there is very pleasant for working.”

.

.

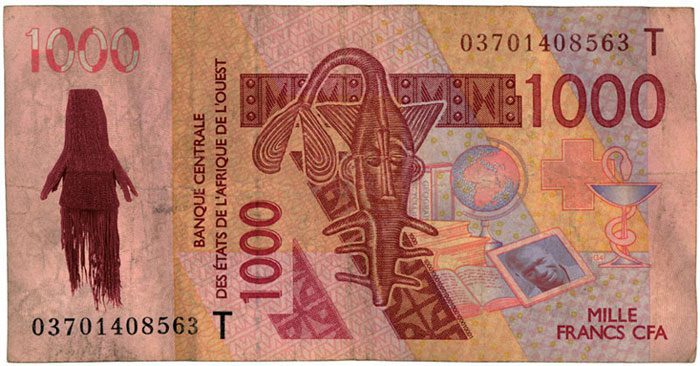

Gaba’s first exhibition with his New York gallery dealer Tanya Bonakdar was on view this summer. In the white cube in New York City, there are market stalls with symbols of value, ranging from gilded stones and cell phones to banknotes. “There is no originality in my work other than my own. In this sense, I have no artistic nationality,” says Gaba, looking over at his children’s two guinea pigs fighting over their lunch in a cage. “I love Benin, but that doesn’t mean my inspiration ends there. I can also do what I do in New York or London.” As an artist, he has worked for years the way many young artists from African countries are discovering they can work today: basing their identity on their own life and not on geographic origins. In 1996, Gaba opted to study at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, for one thing, because the Netherlands and Benin, which was socialist until 1990, do not share a colonial past. “The exchange about my work with colleagues and professors at the academy inspired me a great deal.” One work he created during his two-year stint there was “Bread and Hammer,” a large sculpture consisting of two wooden blocks out of which he sawed a bread shape and several hammers. His work was still influenced by Communism at the time, says Gaba with a grin, eyeing the massive sculpture leaning against the wall. Small works are on display on the mantelpiece and windowsills. Some of them are preliminary studies, including two animal-shaped coin banks, covered with a pattern made from cut-up devalued banknotes from Benin. The large versions of these coin banks, shaped like animals or the logos of African banks, are currently hanging in Tanya Bonakdar’s New York gallery. Banknotes are a recurrent and important component of Gaba’s visual language, and he uses them abundantly to playfully refer to the unstable value of money.

.

Meschac Gaba, Artist with African Inspiration: Salle de Francophonie. 2004 Digital print. Courtesy: M.Stevenson. © M.Gaba

.

The curator and critic Simon Njami describes Gaba’s artistic production as a continuum, an oeuvre in continual development, in which the creations communicate with one another; as though his work is never finished, as though he is engaged in an eternal search for a great solution for a better, functioning society. Indeed, hardly any of Meschac Gaba’s works can be viewed as being singular. They contain recurrent symbols, such as banknotes and flags, and playful aspects come up again and again. Gaba’s most extensive project to date is his “Museum of Contemporary African Art.” The installation grew to twelve rooms between 1997 and 2002 and toured the art world, from documenta 11 to Tate Modern, which purchased the work. Now the “Museum” is on view in the Deutsche Bank KunstHalle.

Meschac Gaba, Art and Religion Room, from Museum of Contemporary African Art 1997-2002 Installation shot at Tate Modern, © Meschac Gaba, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

.

There is a room for religion and art, one for architecture, a museum store, a library, and a restaurant. A chief source of motivation for Gaba’s museum was the notion harbored for years in the art world that contemporary African art is nonexistent. Another early trigger was Jean Hubert Martin’s Paris exhibition “Les Magiciens de la Terre” in the Centre Pompidou in 1989. The exhibition featured spiritual objects, artistic coffins, and sand paintings that were presented as “contemporary African art.” “This show depicted contemporary artistic production in Africa that was not ours,” Gaba recalls. His museum has no walls, he says, emphasizing the freedom he has to show his large installation however and wherever he wants. And when there is no physical museum, no white cube in London, Berlin, or Cape Town, then he creates his own floor plan or uses a different infrastructure. For example, in 2010 he initiated MAVA (Musée de l’Art de la Vie Active), a project he launched in Cotonou, declaring the whole city to be MAVA. A procession-like performance was presented that was later also shown in Karlsruhe. Around thirty people wore wigs made of synthetic hair that referred to historical figures in the history of the world, from Martin Luther King and Kwame Nkrumah to Joan of Arc. By juxtaposing personalities from African history with Western icons, Gaba points to the need for a global narrative. He showed the first of his “Tresses” series, consisting of hair sculptures based on architectural landmarks in Cotonou and New York City, in Studio Museum Harlem in 2005.

.

.

Gaba’s rolling library shows how unexpectedly and humorously he brings the art world and the “non-art world” together in various works. Taxi drivers race through Cotonou during the Benin Biennale, but the artist replaced the license plates with quotes from culture producers, such as “Life=art=life,” and “But this is not the endpoint.” One of the taxi motorcycles stood in the Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town last year, accompanied by the video of the art action in Benin. The presentation of the motorcycle seems like a tongue-in-cheek reaction to what Gaba found for years in ethnological museums: everyday items— the tools of “the others”—which in the display case had suddenly transformed into objects with no real context.

.

.

Meschac Gaba’s art is there to play with and he presents it like a game master with a penchant for political satire. At the Tate Modern show, adult visitors lay on their stomachs and erected their ideal city out of building blocks. In “Rules of the Game” (2001), he had countries compete by inviting visitors to play table tennis with a different national flag on each paddle. The painting “Citoyen du Monde” shows the flags of the countries of the world, which Gaba hurtles toward a point in the distance. The type of portrayal has almost comic-like features, as each country shrinks to the point where it is beyond recognition. There is humor in this work, but not cynicism. Rather, it symbolizes Gaba’s absolutely confident vision of non-hierarchical interaction between people. First,though, he wants to initiate a very concrete museum of contemporary art in Africa. “But not a copy of a Western museum,” he says, putting on his sunglasses. The temperature outside is now in the nineties, and Gaba needs to do some quick shopping. “I dream of a museum without walls, in the form of a village, where artists can live, produce, exhibit, and sell their works.”

Julia Grosse is chief editor of Contemporary And (C&). This feature initially appeared in Art Mag by Deutsche Bank.

More Editorial