The Stories Between Us

3 Février 2016

Magazine C&

15 min de lecture

‘The Work Between Us: Black British Artists and Exhibition Histories’ [The Work Between Us – Full Symposium Programme] was held at The Bluecoat, Liverpool. This is a research context that I would not usually jump into (especially right at the end of my PhD) however, it examined contexts of curating and translating (trans)cultures, and the placement …

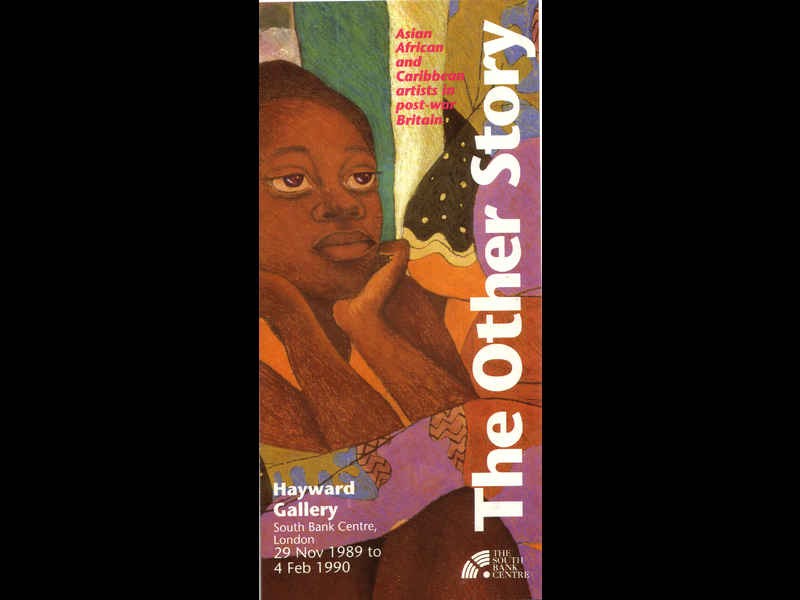

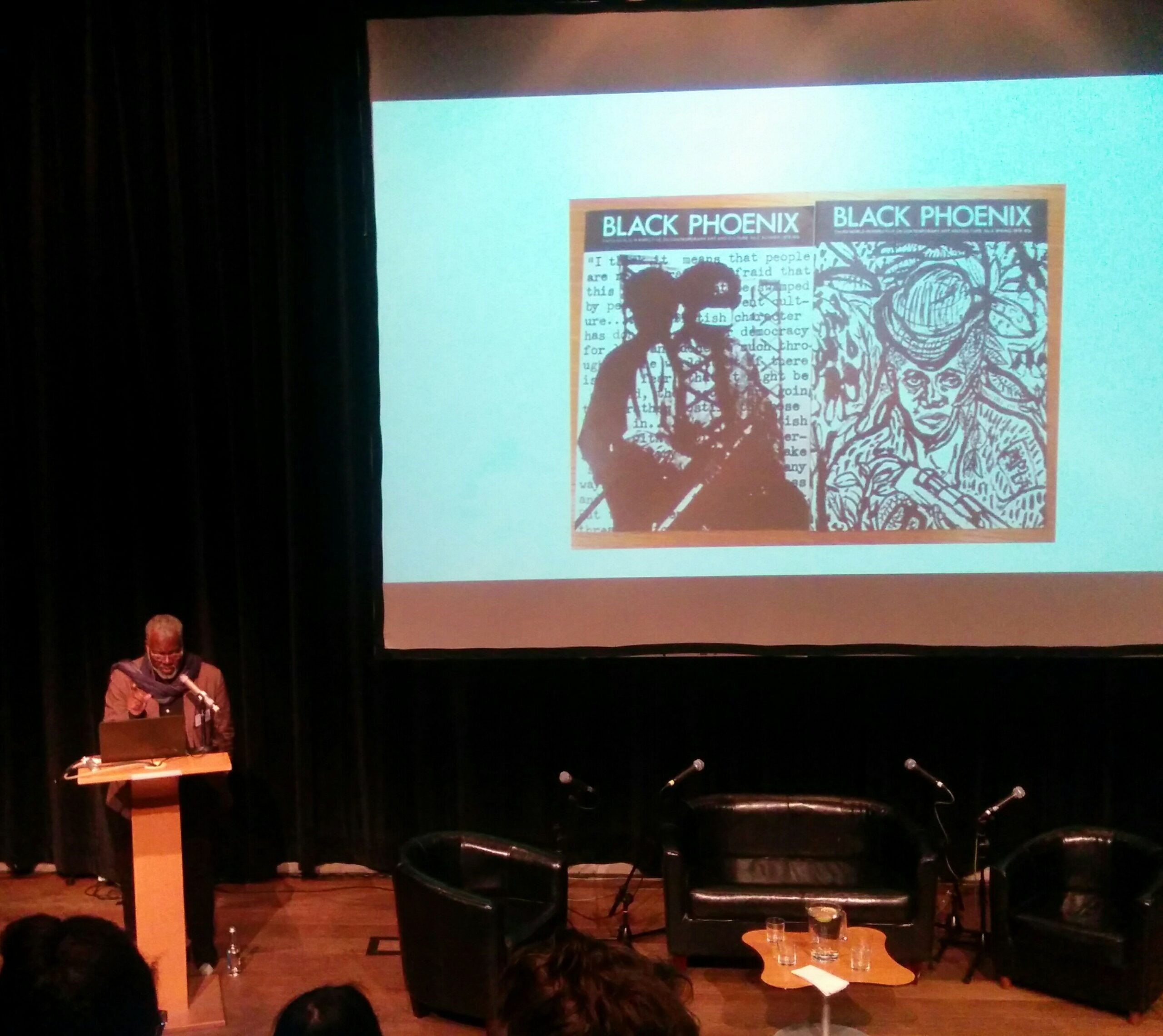

‘The Work Between Us: Black British Artists and Exhibition Histories’ [The Work Between Us – Full Symposium Programme] was held atThe Bluecoat, Liverpool. This is a research context that I would not usually jump into (especially right at the end of my PhD) however, it examined contexts of curating and translating (trans)cultures, and the placement of Chinese arts under the umbrella of “black arts” in the 1980s…the latter I am very interested to know more about, especially in relation to the languages used to define Chinese art in the UK at that time.Sonia Boyce began the day with ‘Presumed Outside – The Other Story and Exhibition Histories’.The Other Story was a national touring exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in 1989-90 curated by Rasheed Araeen. It was a contribution of African and Asian diasporic artists to modernism and contemporary art…then “groundbreaking”. How they relate to modernism and how they have contributed to the story of twentieth century art. At a time preoccupied with race and racism…where was the “elsewhere” situated and how was it different to the “here”…how did it relate to the artwork and institutional racism?

At that time, Brian Sewell was the critic of the year – his words were taken seriously. Modernism’s ambition was that it would be seen as a universal language…who can speak the language of modernism, its modernist terms…and who was outside of this “language”.

1989 was an important year socio-politically and culturally. Although The Other Story is seen as a key exhibition of black arts, contributing to the history of black arts in the UK, it is also seen as a parochial event in art history….the most requested archive in the Hayward archive collection.

The opening paper was ‘Retelling ‘The Other Story’ Now’ by Lucy Steed. A revisitation of the exhibition atHayward Gallery. It is through the exhibition catalogue that the exhibition has become so well researched.

</a> Paul Goodwin, The Work Between Us. Photo by Rachel Marsden</figure>

The exhibition was a ‘tricky contraction and unity of Afro-Asian artists of post-war Britain.’

Show sections included:

<ul>

<li>‘In the Citadel of Modernism’ (‘Humanism and Figuration’ and ‘Towards a New Abstraction’) artists beliefs in modernist aesthetics and a modernist commitment to media specificity, all male artists;</li>

<li>‘Taking the Bull by the Horns’ groups artists who address not only the questions of art as an outcome of bourgeois society but with a connection to life as a whole, art as activism and the critical function of art, incorporating the utopian vision of art as an ultimate goal, art as an idea, again all male artists including Chinese artist Li Yuan-Chia. Li onto show at Signals, Lisson Gallery, ICA London, MOMA Oxford, LYC in Cumbria (which ended in 1989) where Li’s work then become hard to access;</li>

<li>‘Confronting the System’ and ‘Recovering Cultural Metaphors’ offered two paths and then 1980s readings of contemporary art. ‘Confronting the System’ asked how to address contemporaneity and art of the present. Post-modern art on the one hand and post-conceptual art on the other. Post-colonial thought sharpens the post-modern mind;</li>

<li>The final room ‘Recovering Cultural Metaphors’. Post-modern and the post-conceptual…does it fit here or there, upstairs or downstairs…the palpable viability of post-modernism at the time and the creation of an alternative art regime through post-conceptual art.</li>

<li>The density of the show creates a laboratory. There is a certain didacticism through the linearity of the show. It addresses art history and is therefore, a canonical presentation so needs to speak in those curatorial terms. Some artists didn’t want to be ghettoised or put in this box…often a career and political decision for artists not to be part of the show.</li>

<li>Other questions included:</li>

<li>Is there an absence in the exhibition?</li>

<li>Is there such a thing as a “black aesthetic”?</li>

<li>How are specific forms of medium part of the debate about Afro-Asian arts practice at this moment?</li>

<li>How did it change an understanding in art history?</li>

<li>How do you find the discursive impact of the exhibition beyond the catalogue?</li>

<li>Professor Paul Goodwin followed with ‘Eleven Years: Notes Towards A Pre-History of The Other Story’. His paper talked through the eleven years it took Rasheed Araeen to conceive the show through three frameworks:</li>

<li>Conjunctional analysis;</li>

<li>Plotting the course and the eleven year period;</li>

<li>Speculative conclusion of a pre-history and what it means for exhibition histories.</li>

<li>The Other Story was framed within a Eurocentric understanding of modernism, what was called “a cold shoulder”, specifically from the Arts Council:</li>

<li>“There are cracks and crevices in its white pyramid by which on can penetrate its inner space. The Other Space is a story of this explorations” – Rasheed Araeen (Postscript, The Other Story Exhibition catalogue, 1989)</li>

<li>“Polyvocal” and “hybrid” art practice as a new representational space that the black arts emerged in the 1980s.</li>

<li>“When the historical conjuncture changes – as it did significantly between the 1960s and the 1980s and again, between the 1990s and the present – the problem space, and thus the practices, also change since, as David Scott puts it, what was a ‘horizon of the future’ for them has become our ‘futures past’ – a horizon which we can ‘no longer imagine, seek after, inhabit’, or indeed create in, see or represent in the same way.” – David Scott [Black Diaspora Artists in Britain article].</li>

<li>Critic after critic framed the work of black artists in social or political terms rather than in the terms of the art itself…“secret semiotics leading the way to secret puzzles”…“the aura of the primitive unleashed”. This creates a “theatre of refusal” for black arts…when compared to the “white pyramid”, renders visible the role of the white critic during the eleven years of planning.</li>

</ul>

Sophie Orlando’s paper ‘The Other Story, La Méprise’ examined the exhibition as a story of misunderstanding. How does art criticism write The Other Story? There is a clear lack of analysis of the exhibition…they rewrite the legitimacies used to describe modernism. One clear misunderstanding is the lack of criticism of modernism.

She cited a case study in comparison to The Other Story –Multiple Modernities 1905-1970 at Centre Pompidou in 2013 [PRESS KIT MULTIPLE MODERNITIES] and understandings of “PRIMITIVISM”. She noted phrasing and descriptions – the centre versus periphery, the artists as manipulators, exoticism and “otherness”, older versus younger artists, colonial views, relentless assaults of devaluation, primitive and primitivism, and occidental art.

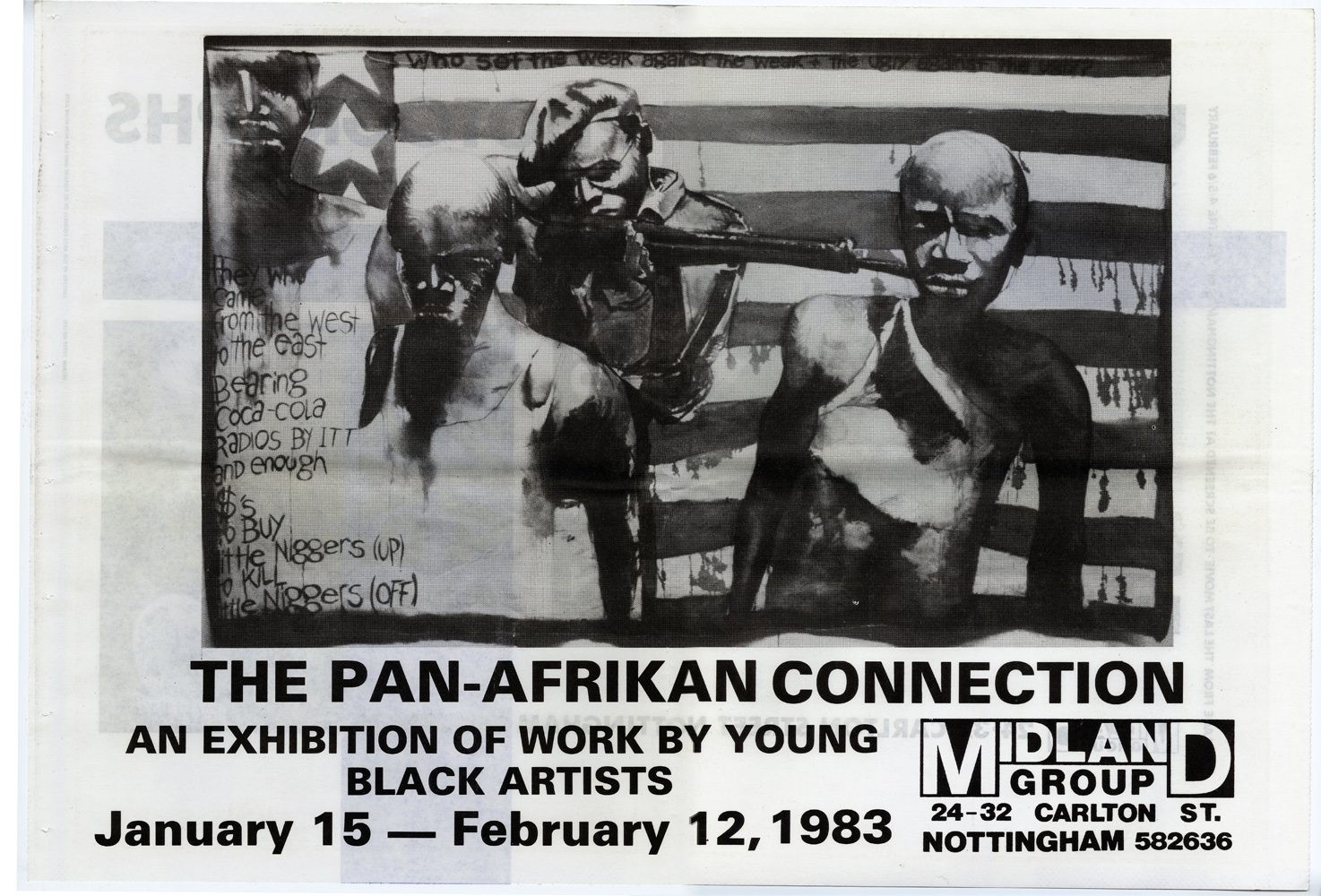

</a> The Pan-Afrikan Connection exhibition poster, 1983</figure>

The final paper before lunch was ‘Where are the Asian Artists? The Horizon Gallery Responds to The Other Story’ by Alice Correria. She opened by discussing who and who wasn’t selected for the show and the palpable tension at the opening…specifically over the lack of South Asian artists and those artists who had migrated to, not been born, in Britain. She questioned why exhibitions of this kind are necessary in relation to the work of the Horizon Gallery, London. According to Rasheed Arareen, The Other Story was ‘never meant to be a contemporary art show but a historical exhibition’. Horizon Gallery was initially seen as a space of defeat (in response to setting up a space explicitly for Asian art), not interested in questioning the system and representative of only their cultural backgrounds. What impact did the Horizon Gallery have and its legacy? It offers us access to another “other story” that is waiting to be written.

Whilst image searching, I came across this poster for the 1983 exhibition The Pan-Afrikan Connection. After the mornings words and deliberations, it made me consider the role of language, terminologies and definitions in defining, creating and (mis)translating an art history, here black British artists and exhibitions histories.

Questions unravelled in my head on this and in relation to the perspectives on The Other Story:

<ul>

<li>Who is the definer? The curator, the funder, the audience, the artists, the critic? In the case of The Other Story, it seems that the critic held the power of translation and through the canonical tunnel vision of Eurocentricism, therefore responsible for mistranslations…</li>

<li>The artists create a visual language yet their works are often mistranslated through textual translation. Does the visual always need a textual prop?</li>

<li>Do languages and definitions restrict rather than encourage discursive criticism and critique?</li>

<li>Can we only understand an art history through reflection, revisiting, re-understanding rather than in real-time when the exhibition is taking place? Will we always try to place the exhibition within other past art histories?</li>

</ul>

Funnily enough some of my thoughts were raised by other audience members in the end of morning panel, where discussion unfolded into questioning:

<ul>

<li>Geography and the geographical frame;</li>

<li>Black arts in the wider frame not just the UK at the time of The Other Story;</li>

<li>The understanding of contemporary art is a global formation and framing – you can’t understand modernism within a national framework, it has to be transnational (Paul Goodwin);</li>

<li>The illusion to “otherness” in the title…does this title-ing separate ethnicities in terms of art? The other story implies there is only one story to be differentiated from. The rhetoric at the time was “multi-culturalism” at the time…main issue at the time that it is compared to one other story, the other story of modernism;</li>

<li>Paradox of trying to undo a dominant discourse…we have to think about it in terms of tactics, not as essentialism. This comes through conjunctive thinking (Paul Goodwin);</li>

<li>In the geographical and temporal shifts, there are shifts in the signification of terms. There are references and illusions to the ways in which Black, Afro-Caribbean, Asian have signified particular individual and places at particular moments. The terms continue to be in flux and produce problem spaces (Susan Pui San Lok);</li>

<li>Were there any unified languages that were used? What is a modernist critic? What do they do and what do they create? Are we in or out of modernism or centre or periphery to modernism? (Ella S. Mills)</li>

<li>It is a temporal rupture…a moment of radical conceptual strategies…what apparatus do we use to create an archive? (Ella S. Mills)</li>

<li>Is The Other Story stuck in a void of acceptance? The way the language has been framed Afro-Asian, it does create some sort of restriction. Are black artists or Asian artists stuck? Or are they stuck in a straight jacket of trying to fit into something that is never going to fit for them and reconnect with what makes them, them – are we caught in the frame of the canon? Or always being “the other story”?</li>

</ul>

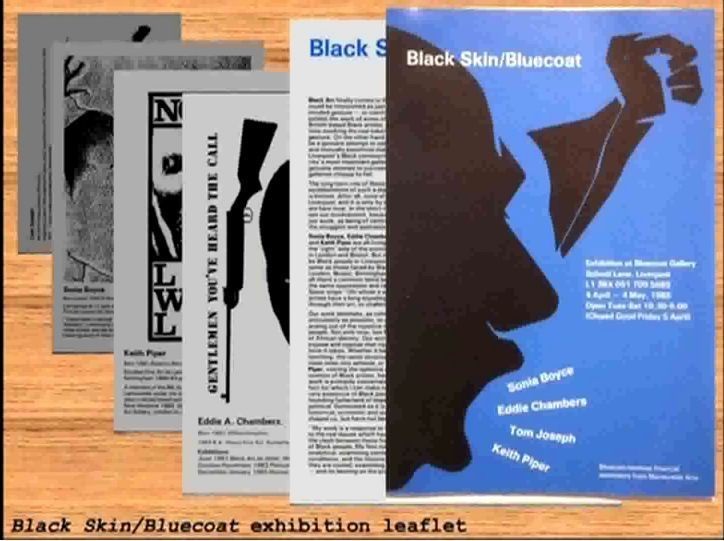

After a far too brief blue sky wander through Liverpool over lunch, Anjalie Dalal-Clayton began the afternoon with ‘Re-Cognising Black Skin/Bluecoat’, a case study of the four-week exhibition in Liverpool in 1985.

Black Skin/Bluecoat exhibition leaflet, 1985 “There is limited mileage in collectivising and exhibiting the work of individuals linked by no other factor beyond the colour of their skin. If ‘INTO THE OPEN’ is to be seen as it is, an important first step then once in the open, individual Black artists should be given access to the type of total control” – Keith Piper The catalogue was to act as a form of consciousness raising versus looking into the politicising of black people. The representational and referential as part of the exhibition showed its relationship to 1980s avant-garde. What happens to our memory and understanding of an exhibition if we look at media, style, the artists and lineage? Text and image beyond linguistic tradition from printed, typography and hand-written texts creating a double narrative arch both visual and textual, AND personal and political. Here, modernism was the appropriation of culture and the society at large, appropriating the status quo. Text was conceptual through vision rather than perceptual through language. Jean Hui Ng, the new research curator atCFCCA presented ’30 years of exhibitions at the Centre for Contemporary Chinese Art’. Bluecoat turns 300 next year versus CFCCA turning 30 this year, which put things into perspective. CFCCA originally began as the Chinese View festival in 1986, then the Chinese View Arts Association in 1988, organising workshops for Chinese children to understand their own Chinese heritage…celebrate their culture and way of life. At that time, the Arts Council coined African, Asian and Chinese Arts as “black arts”. Focussing on its annual festival, to space in the northern quarter, now to its RIBA award-winning space in Manchester’s Northern Quarter. In May 1992, Chinese Arts Centre opened the project ‘Beyond Chinese Takeaway’ acknowledging there was very little recognition of the talent inside and outside of Manchester’s Chinatown. Then more of a cultural centre, it moved into a new space on Edge Street to become more of a visual arts centre. Locations and dislocation of Chinese art across the world…web of knowledge began to develop CAC began to show artists outside of China. “Assessing the cultural through a critical lens of pastiche and parody.” Open the debate of the role of Chinese arts and it’s relationship to the black arts through conferences (‘RE:ORIENT, RE:ACT’ and ‘New Moves’ (1999) at V&A). Umbrella terms of cultural diversity and black arts were too broad for the contexts within which they worked. A new vocabulary for Chinese art…consolidate and rethink…build a larger narrative for Chinese art. Jean cited the work and projects of Suki Chan and Xu Bing as examples of visual hybridity, including cultural objects, which were placed in a liminal hybrid space of political, social, cultural and colonial histories. ‘The Image Employed: the use of Narrative in Black Art’ was a conversation rather than a paper presentation between Bev Bytheway, Keith Piper and Marlene Smith, moderated by Alice Correia. They spoke about their mutual experiences of the exhibition ‘the image employed‘ (1987) at Cornerhouse, Manchester. What are the images and objects within black arts doing? Questioned in relation to the “image employed” or the “image deployed”. The exhibition functioned as a proposition. In terms of the title, it was a tension and gap…where the subtitle would also shift the direction of the exhibition and would change the ways in which the artists responded and also the writers, writing about the show. The idea of a strategic anxiety at that moment that was shared by practitioners at that time…how do you approach or leave a trail of your discourses in a gallery? Was it a tokenistic gesture on behalf of the gallery? It arose from a set of intimate conversations and friendship groups where it could be seen as nepotism…whereas Keith Piper saw it as a growing set of responses to those social spaces – a recognition of these groups of people, ideas generation through conversation. It was reflection of the current debates at that time. Time for the final plenary session…opening with comments from Nina Edge: White art palace curated by a black man and showing work of a paki…”noisely black”… The work was viewed by critics…did it fit the expectation of what art should be? What should go in a culture palace? Did it give visibility to culture and art-making? Who do we expect to be there and is it ok to be there? Would it still be logical to have a black art expectation now? Can we reach a point where art is defined by its cultures or visual deliverers? By discussing the black perhaps it lets us avoid what arenas it may fall into. Is the white mainstream going to constantly be a tourist in the worldwide cultural environment? There is oriental symmetry to this. Leon Wainwright responded to these set of questions speaking of his academic experience since 1997 and research into Caribbean artists. Historiography and canonisation are about archiving and recollection. There were ways in which black and asian artists contributed to the academy in 1980s and early 1990s. What kinds of “histories” have been used as exhibition approaches? The rhetoric of multiculturalism relating to funding patterns were banded together in an ideological fashion…it is our role to transcend this and find value beyond this and balance our problems of difference and division along racial lines. There has to be something more about art-making, another basis for understanding for these kind of exhibitions that go beyond social and racial explorations. It is about brokering social relationships and acknowledging changes over several decades. Susan Pui San Lok stated some of the most interesting things happen between the exhibitions through the conversations and dialogues. She acknowledged the strategic alignment of Rasheed Araeen’s work now part of the Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong, now in a place that reminds us of the narratives of colonialism and imperialism. She referenced back to Jean’s paper and the subsumption of Chinese art under black arts…this was a bureaucratic arts administrative categorisation only and reminded her of Sarat Maharaj’s multicultural managerialism. There are Chinese shows and interrogations on why the categories and distinctions succeed or fail. An exhibition history that hasn’t been spoken about today that speaks more of subsumption is Lesley Sanderson’s exhibition These Colours Run (1994), another show that highlights the problematic reductive readings of black art and art of colour. This article was first published on the author's blog, Rachel Marsden's Word. Rachel Marsden is an arts writer, curator, researcher and educator.

de

Critique

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir : surréalisme, abstraction et figuration panafricains

de

Curation

Naomi Beckwith présente l’équipe artistique qui l’accompagnera pour la documenta 16

Paula Nascimento et Angela Harutyunyan nommées commissaires de la 17ᵉ édition de la Sharjah Biennial