The Rising Contemporary African Art Brand and the Burden of Africanness

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? borrows its title from Sidney Poitier’s 1967’s epic comedy-drama, a fitting metaphor, in reference to the astute observation of art historian Chika Okeke-Agulu that African artists have indeed mastered the realpolitiks of contemporary art and can now be counted as legitimate stakeholders. They have invited themselves to the dinner table …

<i>Guess Who's Coming to Dinner? </i>borrows its title from<i> </i>Sidney Poitier's 1967’s epic comedy-drama, a fitting metaphor, in reference to the astute observation of art historian Chika Okeke-Agulu that African artists have indeed mastered the <i>realpolitiks</i> of contemporary art and can now be counted as legitimate stakeholders. They have invited themselves to the dinner table of the international mainstream on their own terms. The exhibition celebrates this unfolding development without losing sight of the fact that the growing acceptance of contemporary art by African artists is a work in progress. It presents works byAida Muluneh, Amalia Ramanankirahina, Amina Menia, Beatrice Wanjiku Njoroge, Chika Modum-Udok, Chike Obeagu, Ephrem Solomon Tegegn, Gopal Dagnogo, Halida Boughriet, Onyeka Ibe, Sam Hopkins, and Uche Uzorka. Though plugged into the circuits of the international art world in various ways, they are not well-known in the somewhat insular New York art scene.

While the understanding of contemporary art has taken on a capacious nature, one observes that the work of a majority of artists from Africa is still mostly read against the grain of how it conveys cultural values or imagined ideas about the continent. The exhibition takes this peculiar system of value as its conceptual basis. Through the works on display, the exhibition problematizes this burden of “Africanness,” which, arguably, continues to inform the reception of contemporary art by African artists in the Western and international imaginary. Yet the twelve exhibiting artists do not disavow their connections to Africa either as a place of birth or a context of immense significance. Individually, they reflect localized experiences, histories, memories, and extant material conditions that intersect with the global or the universal.

Amina Menia focuses on Algeria’s recent past, fraught with colonial violence and anti-colonial pushback, which feed postcolonial anxiety. Her work in the exhibition is a selection from the ongoing photography series entitled Chrysanthemums which captures commemorative stelae and monuments dedicated to martyrs who laid down their lives in service to Algeria during the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62). Uche Uzorka’s connect the past and the present in addressing the challenges of nation building in Nigeria in the riveting ink drawings Alien Citizen, Alien Indigene (2014) and One Night’s Crossing of Color and Dream (2014). His other work Tear and Wear (No Place like Home (2014) explores processes of urban street culture in Lagos.

Though working with a conventional medium (woodcut) and a limited color palette in the new Forbidden Fruit series, Ephrem Solomon’s interlaces bold human figures and visually-arresting geometric backgrounds. Content-wise, they reflect his continued interest in the power relations between the individual and the public. Sam Hopkins examines the mushrooming industry of NGOs in Africa in Logos of Non Profit Organisations working in Kenya (some of which are imaginary) (2010–ongoing). Gopal Dagnogo’s mixed media paintings combine figural, geometric, and abstract elements, some drawn from everyday objects and artifacts with active social lives. With politically charged titles such as Waiting the Vote of the Beasts, no. 1 (2014), and End of an Era No. 4 (2014), Dagnogo draws attention to his sustained interest and engagement with events in his home country of Ivory Coast from his current place of domicile in Paris.

Beatrice Wanjuku’s art finds a delicate balance between how reality is imagined and how it actually manifests. Employing a language of figural abstraction, she addresses the pressure to conform to societal expectations in The Sentiment of the Flesh III and IV (2015) and The Strangeness of my Madness (2015). Amalia Ramanankirahina’s photographic installation entitled Portraits de Famille (2013) charts a historical biography of her family and its intersection with the colonial history of her home country of Madagascar. Her work Le Jardin d'Essai (2013) addresses memory and history as it relates to French colonialism and its aftermath. The Bois de Vincennes was created in 1899 as a site of agronomic experimentation with exotic plants from French imperial holdings. Today, the garden is largely forgotten and in ruins yet remains a monument to colonialism.

Installation view at Richard Taittinger Gallery Aida Muluneh addresses the meaning of blackness in the so-called age of multiculturalism and globalization vis-à-vis the staying power of racism in The Wolf You Feed series (2014). Working with settings and spaces inspired by indoor scenes in Flemish paintings’ and Western pictorial traditions in Diner des anonyms (2014), Bichromie au regard Trompeur (2014), and Les enfants de la République (2014), from the Pandora series, Halida Boughreit presents a remarkable insight on the challenges of belonging and acceptance faced by immigrants and their first-generation French children. Chika Modum’s recent project Outer-Shell (2015) comprises of photographic images of re-purposed human skin types that are fashioned into garments and accessories. New York-based Onyeka Ibe deploys a language of colorful abstraction and conceptualism in Double Walls (2015), Identity (Self-Portrait 1) (2014), and Crumbling Walls (2013). The three works are recent experiments with African architectural forms and built space. Chike Obeagu has a peculiar approach to depicting figural forms by exaggerating facial features such as eyes and lips. His interest in everyday experiences, the banal as well as the poignant, is apparent in Private Viewing (2015), Isi Ewu na Nkwobi (2015), and What It Takes To Get a Pet Name (2014). For those seeking a tangible Africa, there is none in the works of these artists. Africa is neither a label nor a badge of identity and identification. Instead, for Muluneh, Uzorka, Wanjiku, Solomon, Menia, and Obeagu, who live and work from the continent, it is a familiar space of everyday experience. And for Boughriet, Hopkins, Ibe, Ramanankirahina, Modum, and Dagnogo, who live and work from elsewhere, they return to Africa as some sort of archive of received, imagined, lived experience and memory, filtered through their realities of expatriation or emplacement. The longer version of this essay is published as the catalogue’s introductory text ofGuess Who’s Coming to Dinner exhibition currently on view at Richard Taittinger Gallery, New York, from July 16 – August 22, 2015, and curated by Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi.

Contemporary art

Naomi Beckwith présente l’équipe artistique qui l’accompagnera pour la documenta 16

La Biennale de Venise 2026 suivra la vision de feu Koyo Kouoh

Kapwani Kiwanga remporte le Prix Joan Miró 2025

Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi

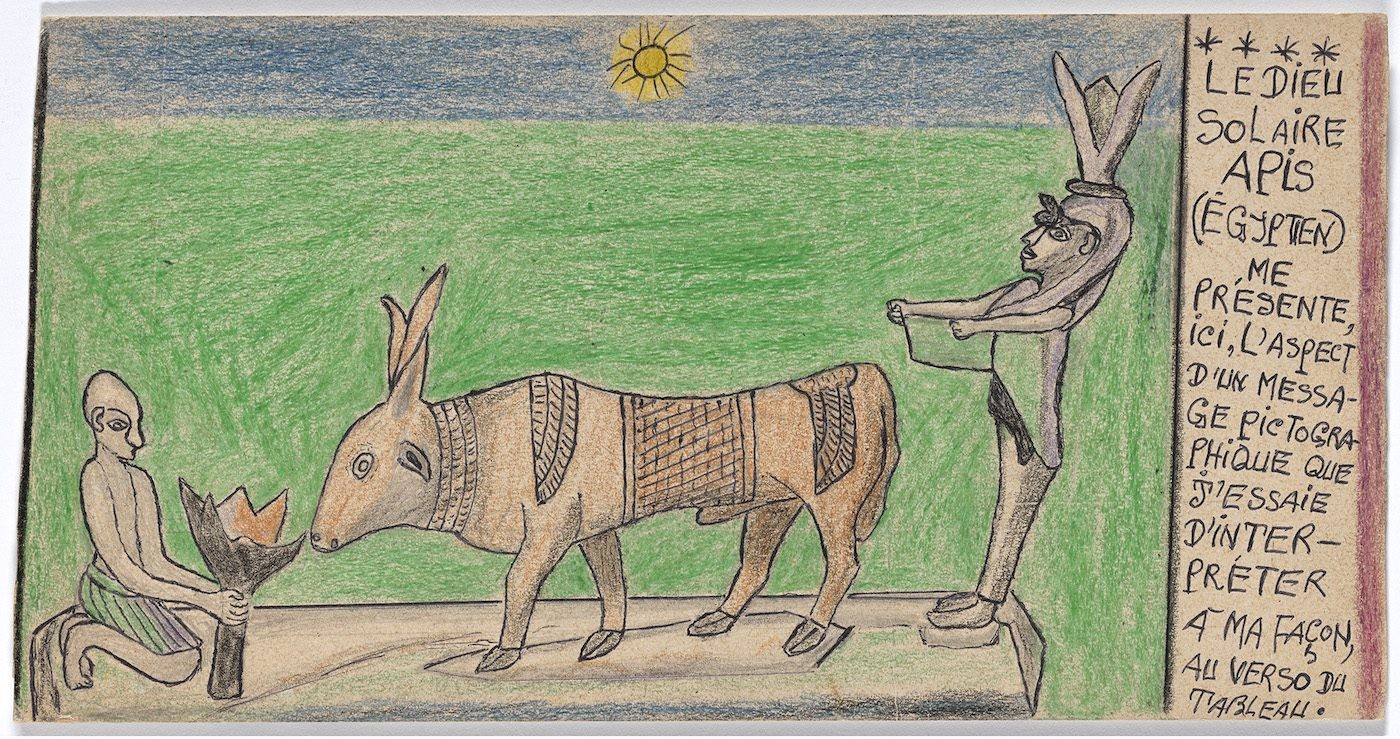

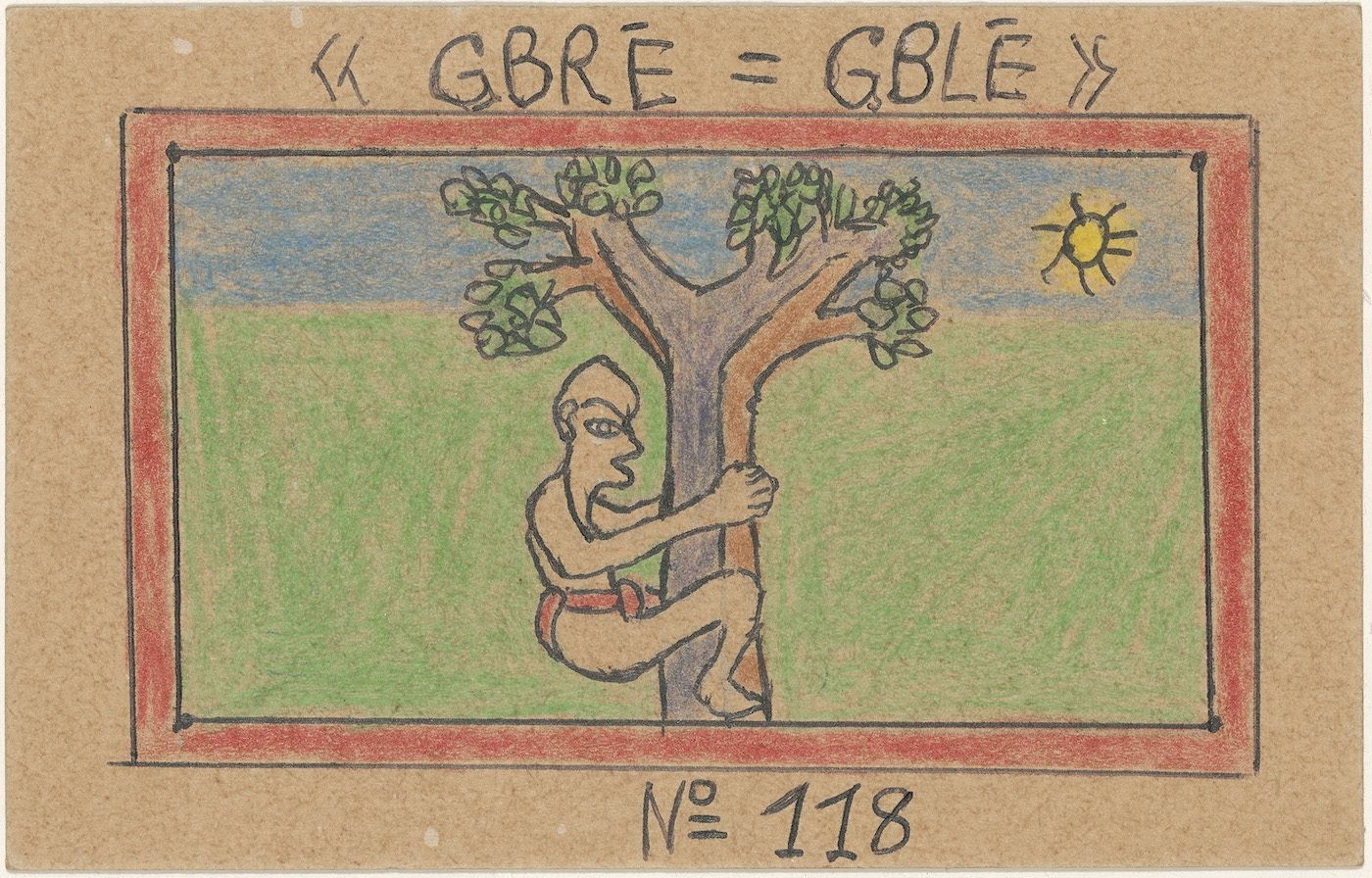

Substance et contexte contre les erreurs d’interprétation : la rétrospective de Fédéric Bruly Bouabré au MoMa

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: World Unbound