The Midcentury Style

04 October 2017

Magazine C& Magazine

Words Dagara Dakin

8 min de lecture

Fatoumata Diabate’s traveling studio revives the golden age of Malian studio portraiture.

Fatoumata Diabate is one of a few women in Mali who practice photography professionally. Born in 1980, she first appeared on the photography scene in 2005 during the sixth edition of the venerable photography festival Rencontres de Bamako, also known as the Bamako Biennale, where her work was awarded the Afrique en Créations prize from the Institut Français. After studying at the Center for Photographic Education (Centre de formation de la photographie/CFP) from 2002 to 2004, she interned at the Center for Professional Education in Vevey (Centre d’enseignement professionel/CEPV) and another at Central DUPON’s professional printing laboratory in Paris. In 2010, following a World Press Photo training workshop in Senegal, she has undertaken various photo reporting projects.

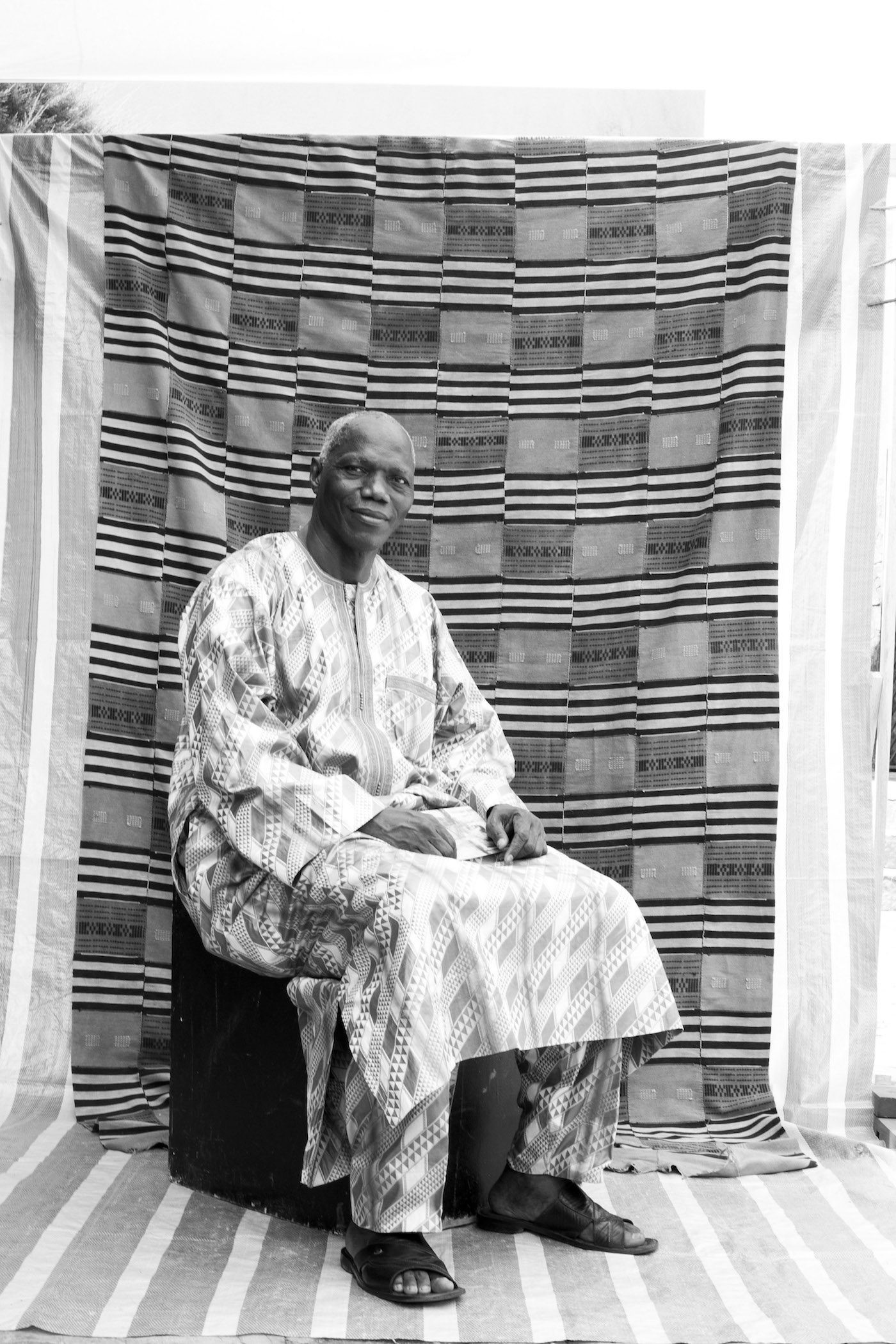

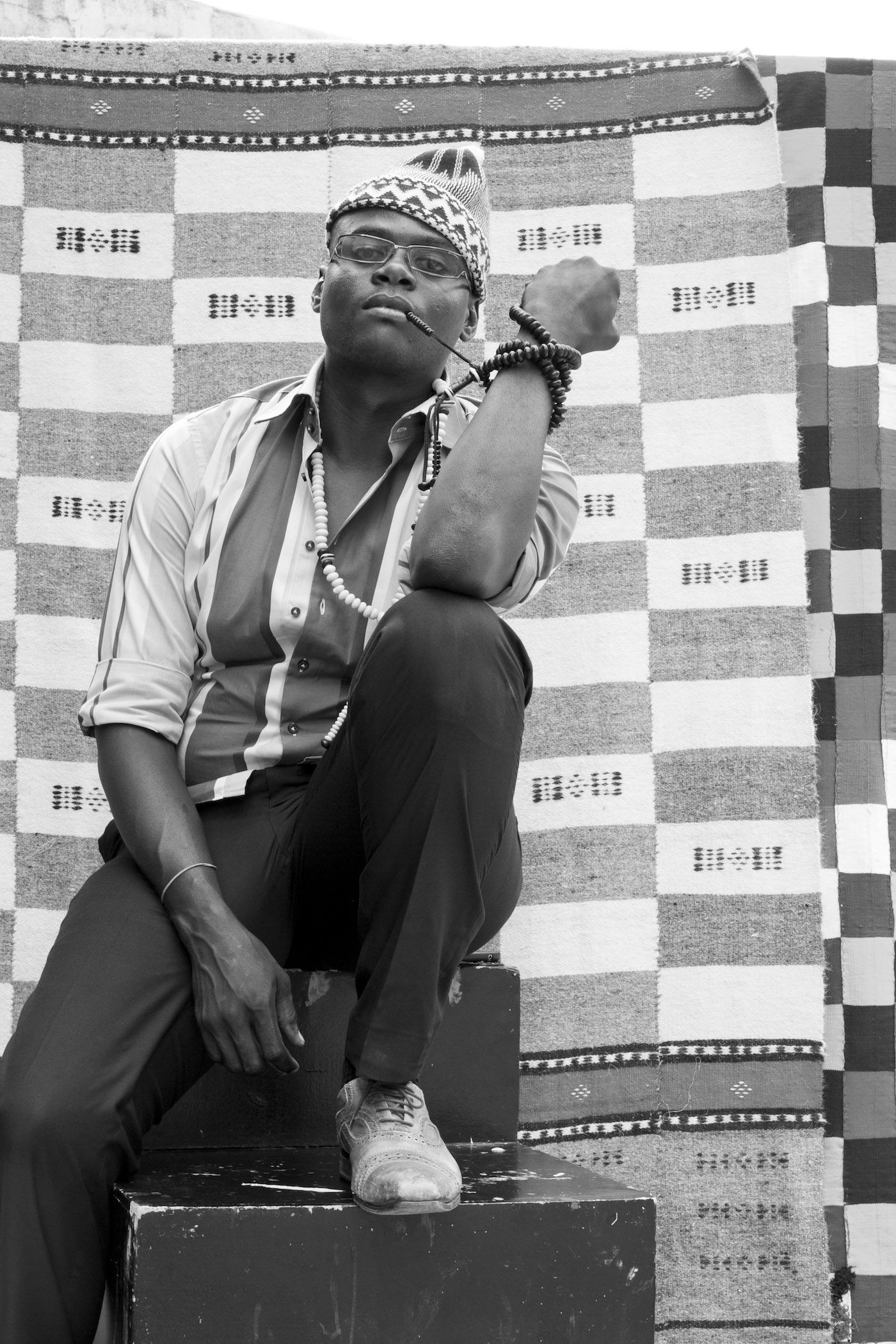

As Franziska Jenni wrote in Aperture’s summer 2017 issue, “Platform Africa,” Diabate’s most recent project, Studio Photo de la Rue revives Mali’s famous portraitists Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé. Her mobile studio, where subjects pose in front of a textile backdrop, “is a stage-like, open-air installation” that become a performance. “The final portraits create something of a time lag: Diabate’s twenty-first-century clients enter her small time machine, which transports them back to the golden age of studio photography in Bamako.” When we spoke recently by email, I was curious to learn more about Diabate’s practice by revisiting her career and touching on her current projects.

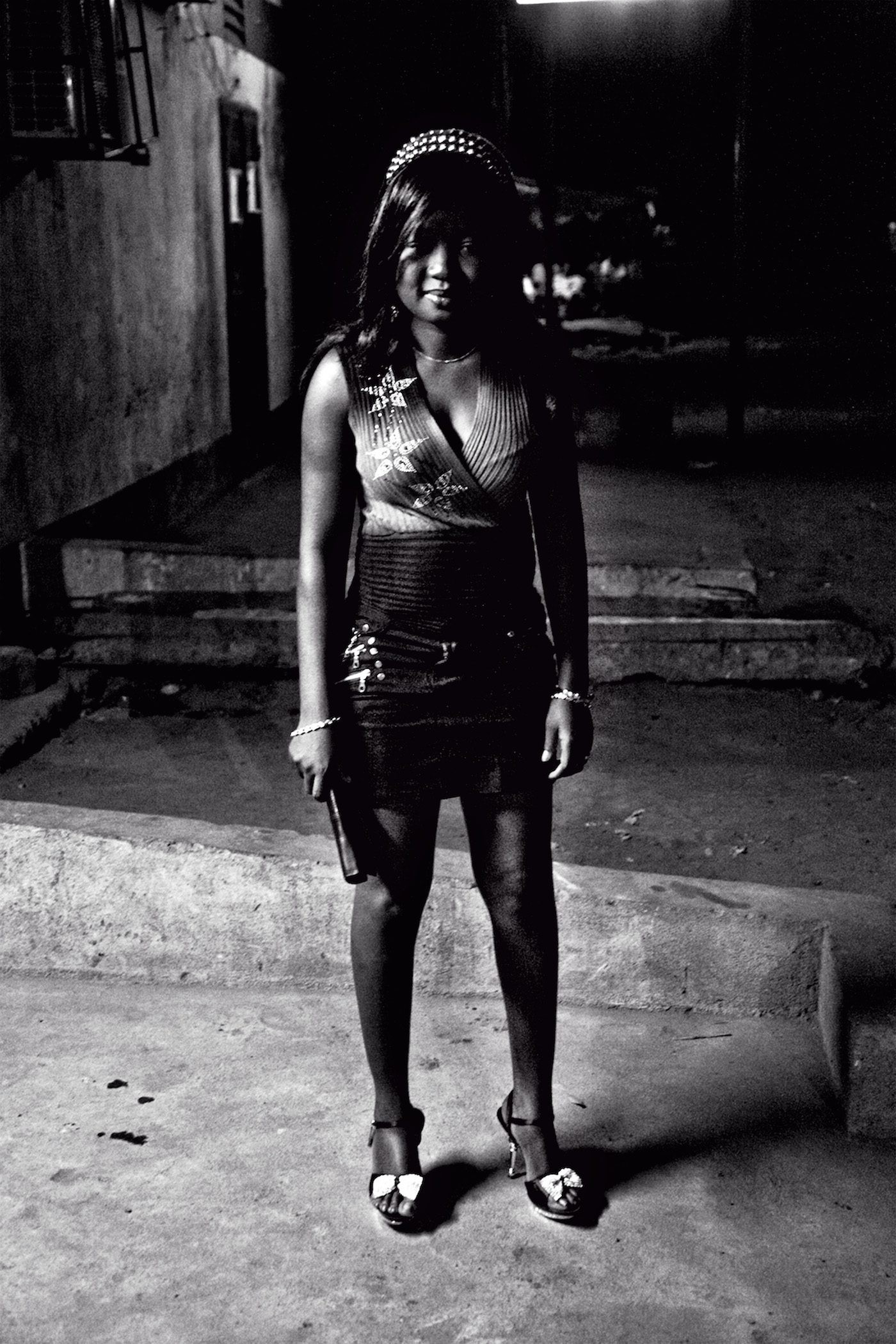

Fatoumata Diabate, Portrait of Sali, Badialan 3, Bamako, 2012, from the series Sutigui (à nous la nuit). Courtesy the artist

Dagara Dakin: What has the Bamako Biennale meant to you?

Fatoumata Diabate: The Biennale’s role is to make young photographers known internationally. I can testify that it has opened numerous doors for me: residencies, exhibitions, publications, et cetera.

DD: Do you think that this event still holds the same place that it used to occupy in the West African photography scene at the beginning of the 2000s, even though it was suspended after the 2011 edition before starting again in 2015, under the artistic direction of curator Bisi Silva?

FD: Mali is a very large country with a lot of cultural diversity. At the same time, it is a big family. Bamako, the capital, is a city that represents this rich mix of populations: Toucouleurs, Bambaras, Bozos, Dogons, Fula, Soninkes, Mandinkas, Khassonkés, Songhais, Tuaregs.

In the same way, Americans, Europeans, and Africans from across the continent come together during the Bamako Biennale to celebrate the love of life, the beauty of the encounter, and the need for the other’s gaze, in all its diversity. So, it is a major event of our time at the national level, the West African level, and on the international stage.

Fatoumata Diabate, Portrait of painter Abdoulaye Konaté, Bamako, 2015, from the series Studio Photo de la Rue. Courtesy the artist

DD: The Biennale is designed to serve as a showcase to the actors in the international art market. It also aims to enable healthy competition among the continent’s photographers. Do you have the sense that the Biennale is well-established at the local level, that the public supports the event?

FD: I can say that, thanks to the Bamako Biennale, other young people have found inspiration in me and my work, like at the presentation of the Afrique en Créations prize that I received in 2005, for example—people like Amsatou Diallo, president of the Association of Women Photographers of Mali, who, incidentally, has proposed to pass the torch to me in that position, or Bintou Camara, and so many others. All of these educational centers have been created to go along with the Bamako Biennale. In addition, to make the show even better established locally, my partners and I are in the process of setting up an “Inter-Biennale,” which will last a month and give pride of place to photography studios from Bamako’s various neighborhoods.

DD: You have done a number of photo reports, notably for World Press and Oxfam. Is that a way for you to take up a commitment in relation to the African continent?

FD: The reports for Oxfam and World Press, as well as for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Rolex, OMS, and others, allowed me to put my gaze to the service of humanist causes and to gain artistic autonomy.

DD: How do you reconcile the practice of photojournalism and NGO-commissioned reporting with your artistic process? What distinction do you draw between the two approaches?

FD: I work in and combine these two practices without difficulty. While taking into account the constraints of photo reporting, I allow myself to tell stories, to have personal points of view. The people who commission photo reports welcome so-called artistic images, such as detail-oriented work, for example, or sometimes abstract depictions.

Fatoumata Diabate, Caméleon.20, Senegal, 2015, from the series Caméléon. Courtesy the artist

DD: The question of the mask and, consequently, of identity reappears rather frequently in your photographic work, whether it is in the series L’homme en animal (Man as animal, 2011–13), L’homme en objet (Man as object, 2012–13), or Caméléon (Chameleon, 2015). Could you tell us more about that?

FD: Masks are tied to my culture and my personality. The sacred, ritual, even mystical dimensions speak to me and call me back to the world of my childhood. The tales that I have heard are still with me and are a source of creation for the series L’homme en animal or L’homme en objet.

DD: Do you ever establish a protocol or set rules for yourself that you force yourself to follow during a shoot, depending on whether your projects are of a documentary or artistic nature?

FD: For me, the protocol of a shoot comes down to respecting the main principle that I learned during my education: the subjects (the people) should recognize themselves in the image, and the image should speak to its viewers, whether it is abstract, a landscape, or a portrait.

Fatoumata Diabate, Portrait 03, Bamako, 2015, from the series Studio Photo de la Rue. Courtesy the artist

DD: What determines the choice of black and white or color in the treatment of your subjects?

FD: Before anything else, I love black and white, especially the gelatin-silver process. Obviously, I do analog photography, but that doesn’t stop me from making color photographs, especially for my latest series, Caméléon. Depending on the subject, I feel at liberty to go back and forth between black and white and color, like in the series Sutigi (à nous la Nuit) (The night is ours, 2012). With that series, I showcase a way of life, a desire to make an appearance that is characteristic of a part of the youth, a testament to my era and to the subject’s ease in front of the camera. In view of our traditions, we feel better at night than during the day.

DD: What place do you give in your work to the condition of women in Mali or on the continent, and what form does that take?

FD: I want to bear witness as an African woman who practices photography. There are a few of us (Aida Muluneh, Joana Choumali, Zanele Muholi, Nontsikelelo Veleko, Ayana V. Jackson, Hien Macline, among others) who have gotten a solid reputation on a global level, but it remains difficult to make one’s place on the African continent, outside the shows dedicated to photography. In a more general sense, in Mali, the civil service gives women roles as secretaries, accountants, and the like. In Bamako, the capital of African photography, despite our results and our commitment to the field of the image, we are hardly given any consideration for our creations. If you compare the status of women photographers in West Africa to that of their peers in South Africa, you will see that the latter enjoy a great reputation, and that that has led to the emergence of a new generation of artists in South Africa.

Fatoumata Diabate, Mah-Traoré ka boutiki, Bamako, 2012, from the series Sutigui (à nous la nuit). Courtesy the artist

DD: What are your current or future projects?

FD: I have recreated a mobile studio, Studio Photo de la Rue, which is an installation inspired by the photography studios of the 1950s and ’60s in Mali and West Africa, and which allows everyone to see themselves through the lens, alone or in a group. The participants leave with their prints as a souvenir. I offer lots of accessories and costumes, which I use to reveal another dimension, a hidden dimension within every man and woman!

Since its creation, Studio Photo de la Rue has been regularly invited to the biggest international photography shows—the Bamako Biennale, the Rencontres d’Arles, La Gacilly Photo Festival in France, and others—to put on a performance at the exhibitions of masters who used mobile studio photography throughout their existence—Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé, Mama Casset, Oumar Ly, James Bernon, Samuel Fosso—whose historic work we still revere today.

Dagara Dakin is a freelance writer and curator based in Paris.

Translated from the French by Matthew Brauer.

This article is part of a series produced in collaboration with Aperture magazine, coinciding with Aperture’s summer 2017 issue, “Platform Africa.”

Plus d'articles de

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge