The First Artist to Challenge the White Queer Gaze in a Biennial

In this series, C& and ArtsEverywhere commission texts inspired by the books in C&’s Center of Unfinished Business installed at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin. C&’s Deputy Editor Will Furtado is inspired by Biennials and Beyond: Exhibitions that Made Art History: 1962–2002 and writes about the legacy of Glenn Ligon’s pioneering work that unpacks the colonial gaze in Robert Mapplethorpe’s The Black Book.

I have a theory that, albeit not inherently, all art is political and inseparable from identity politics. The former because all artworks communicate the political context in which they were created. And the latter because—unwittingly or not—all artists position their biography and heritage in relation to the worlds around them.

Identity politics as a topic of discussion has been waning in the past years. Yet when it entered the art discourse it rocked a system that had flattened out artists’ very specific differences and particularities beyond the artwork. One of the events that shot identity politics to the top of the Western art world’s plinth was the 1993 Whitney Biennial in New York. Curated by Elisabeth Sussman, Lisa Phillips, John G. Hanhardt, andThelma Golden, the biennial was seminal for its fierce social conscience that challenged the establishment at the time.

Artist Daniel J. Martinez designed admission buttons that read “I CAN’T IMAGINE EVER WANTING TO BE WHITE”. Coco Fusco locked herself in a cage in the courtyard, costumed as a Native American; and Nan Goldin showed pictures of deceased people. Needless to say, the mainstream art media blasted it for being the “wrong kind” of political. A headline in the Village Voice read: “Art + Politics = Biennial. Missing: The Pleasure Principle.” And even Thelma Golden’s very position was questioned by art critic Hilton Kramer simply for being African American.

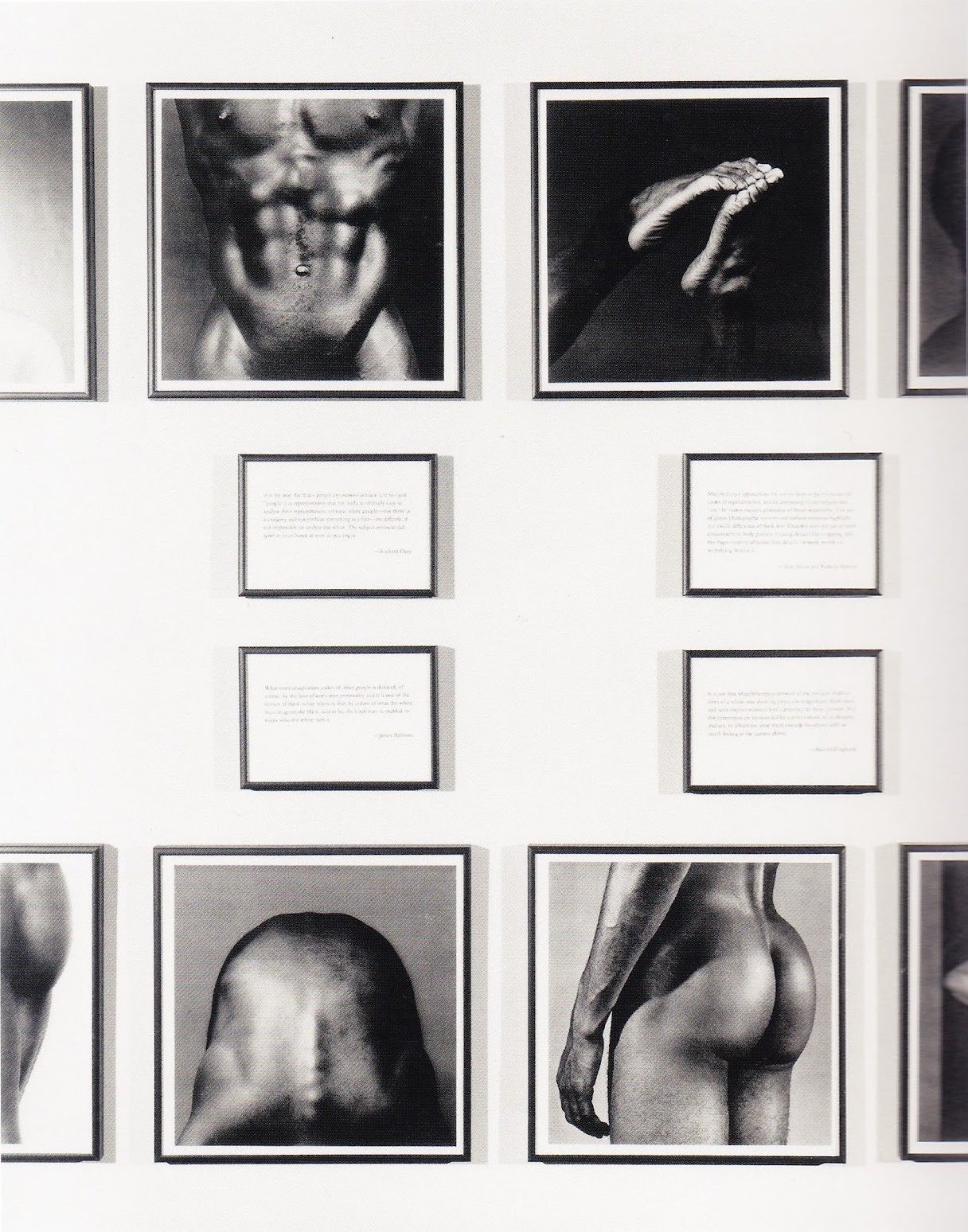

Glenn Ligon, Notes on the Margin of the Black Book, 1991–93. Off-set prints and text, 91 off-set prints, framed: 11 1/2 x 11 1/2 inches (27.9 x 28.6 cm) each; 78 text pages, framed: 5 1/4 x 7 1/4 inches (13.3 x 18.4 cm) each. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York,Gift, The Bohen Foundation 2001.180. © Glenn Ligon. Photo: Ellen Labenski

Arguably all of the artists taking part in the biennial made history and are now well renowned, including Kiki Smith, Lorna Simpson, and Cindy Sherman. However, here I will highlight Glenn Ligon who uniquely and deftly explored the intersection of sexuality, race, privilege, and fetish(ization). The Bronx-born conceptual artist made history by showing Notes on the Margin of the Black Book (1991–93), a series of texts and reappropriated images commenting on Robert Mapplethorpe’s The Black Book.

As the name might suggest, the 1986 book features mostly idealized and homoerotic nude photographs of Black men. When it was first published, Mapplethorpe’s publication split audiences. Some thought it was a stylish homage to the beauty of Black men, others thought it was mindless fetishization, while others claimed it was naive at best. And decades later it’s still divisive. In 2016 the Getty Museum in Los Angeles honored the artist with the retrospective show Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium. The museum decided to include images from the Black Book, but not without explanatory notes.

In addition, the museum in conjunction with LACMA and ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries held a panel discussion about the series which I was fortunate enough to attend. The talk was between multidisciplinary artist M. Lamar, who uses performance and video to interrogate the violent and sexualized surveillance of Black male bodies, and Uri McMillan, the author of Embodied Avatars: Genealogies of Black Feminist Art and Performance. They discussed white supremacist fantasies and the recovery of Black male subjectivity in relation to Robert Mapplethorpe’s Z Portfolio. And what became apparent to me during the talk was that their analysis of the white queer gaze had been heavily influenced by Glenn Ligon’s early critique of it.

Notes on the Margin of the Black Book (1991–93) is pioneering in how it challenges not only the white gaze but also the queer white gaze, while pulling a myriad of references and connecting them to expose a whole system of oppression behind a single unassuming body of work.

Maintaining Mapplethorpe’s initial order, Glenn Ligon had installed two rows of the pages from The Black Book on a wall, sandwiching two rows of typed texts by various writers, thinkers, historians, evangelists and activists. Some of the texts were written specifically for the work, while others offer possible interpretations and contextualize the multiple fears and fantasies that are often projected onto the Black male (nude). One James Baldwin quote reads: “What one’s imagination makes of other people is dictated, of course, by the laws of one’s own personality and it is one of the ironies of black-white relations that, by means of what the white man imagines the black man to be, the black man is enabled to know who the white man is.”

In the imperfect conditions we live in, sex, gender, ethnicity, skin tone, desire(ability), power, money or social status cannot be untwined from art—and by extension everything else that comes from humans. Ligon’s Notes on the Margin of the Black Book (1991–93) as well as many other of his works complicate representations in art and expose the complexities and the importance of identity. And in a world that demands simple explanations and solutions for complex situations, Ligon’s legacy remains as relevant as ever.

by Will Furtado.

C& Center of Unfinished Business is on show until 30 March 2018 in the foyer of Akademie der Künste, Pariser Platz, Berlin.

Essai

The Museum of Black Futures

Sons caribéens : les possibilités connectives de la radio

Cultures Imprimées Noires Canadiennes : de Legs Discrets et Persistants

Essai

The Museum of Black Futures

Sons caribéens : les possibilités connectives de la radio