Where in the primary place of artistic experience do we encounter the Black subject? That is one of the questions that artist Kerry James Marshall has asked throughout his career. MOCA Los Angeles values in the first US retrospective Marshall’s lifelong contribution to the depiction of non-stereotypical Black life

The black in Kerry James Marshall’s work is never accidental or immaterial. Marshall’s black is matte, and deep and it is a reflection: of the Black subject that is often missing from the museum space, of ourselves as Black agents in the space of the visual.

Marshall’s work was born out of the lack of Black images in paintings he encountered during museum and gallery visits as a student. He found that Black artists of the 1940s to the 1960s had increasingly been making abstraction their oeuvre and that the Black figure was largely ignored. Yet he did and does find that it is essential to see oneself in the art on the walls. “It’s psychologically damaging to continue going to places to observe other people in the place of privilege and never finding yourself able to get there,” he says.

Kerry James Marshall, A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, 1980, egg tempera on paper, 8 x 6.5 in., Steven and Deborah Lebowitz, photo by Matthew Fried, © MCA Chicago

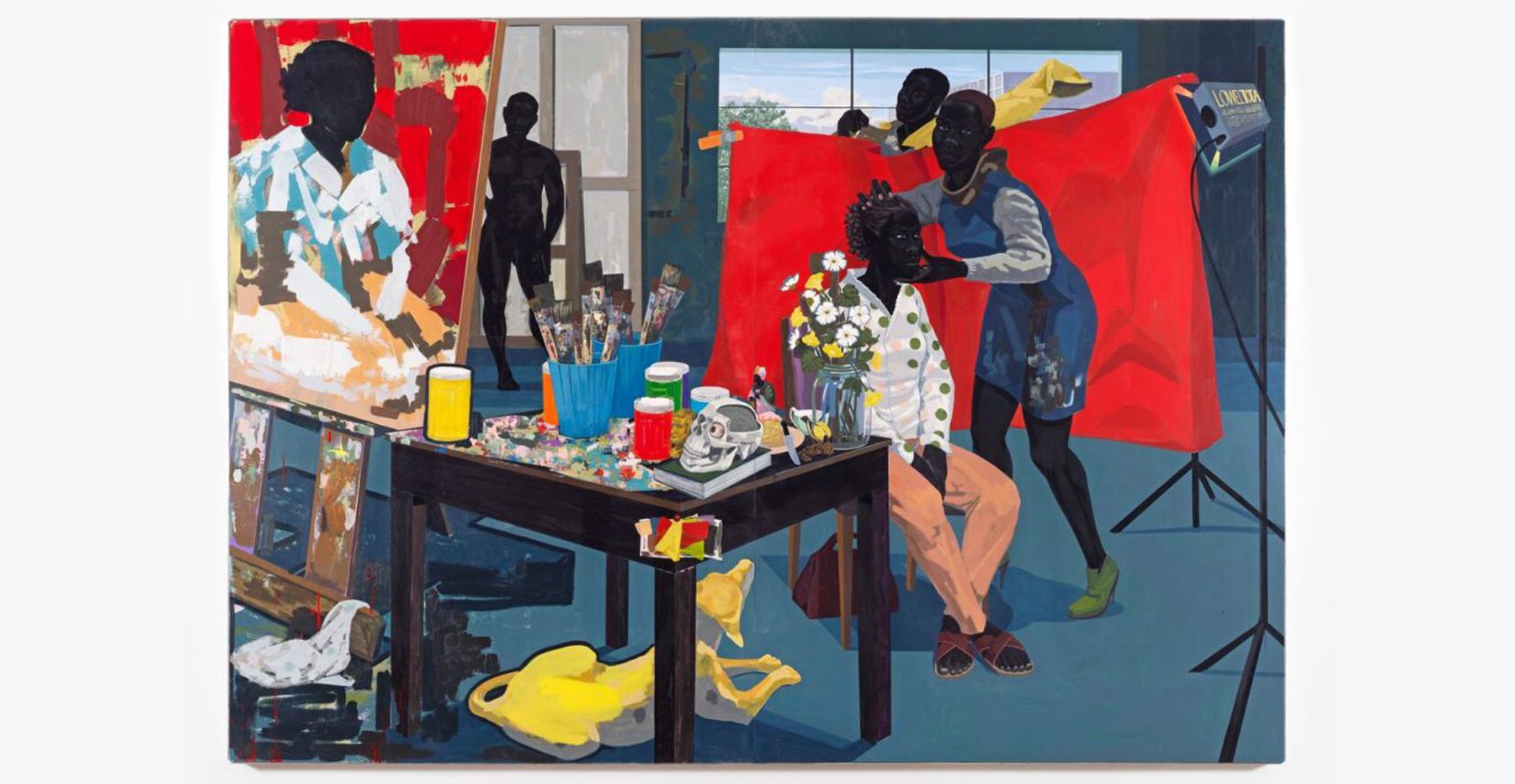

Marshall explains that he doesn’t want his subjects to collapse into one another, but for each one to maintain some form of individuality. He therefore thoughtfully manipulates the pigment to create a multi-textured experience, a practice on clear display in his exhibition The Mastry at MOCA. Marshall uses three types of black in his paintings, derived from various natural sources: iron-oxide-based, carbon-based, and ivory black, originally derived from burned bone. Each black has a different value and as one travels through the museum, it is evident how his understanding of the blacks has changed over the course of his career. Beginning with A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, the black is less dense in contrast to his 2003 Black Painting, a mournful depiction of the minutes before the violent police attack on Fred Hampton and other members of the Black Panther Party in 1969. A similar quality can be found in The Small Pin-Up, where there’s an iridescence to the black, with an illusion of stillness and a ghost-like nature. Somehow the figures in these paintings are all there, but retracted from the surface.

This first US retrospective shows the breadth of Marshall’s work. The dynamism and life of the paintings dance from the walls despite the stillness of the subjects. What Marshall is communicating is vast and will keep you thinking long after leaving the museum. It charts his journey from what he describes as the flat, schematic, highly stylized Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self to what Helen Molesworth, MOCA’s chief curator, describes as paintings with more subjectivity, more of an “individualized” capaciousness.

In a conversation between the two, at MOCA in March 2017, Marshall explained that his entry into the world of painting diverged from many of his peers of the Pictures Generation: “Conceptual Art, Performance, Video, I understood and I had access to all of that too,” he says. “But it seemed to me to not be worth my while to adopt any of those strategies as my primary mode of address when the problem that I thought was most paramount had not been solved. This problem was the one of absence of black subjectivity.”

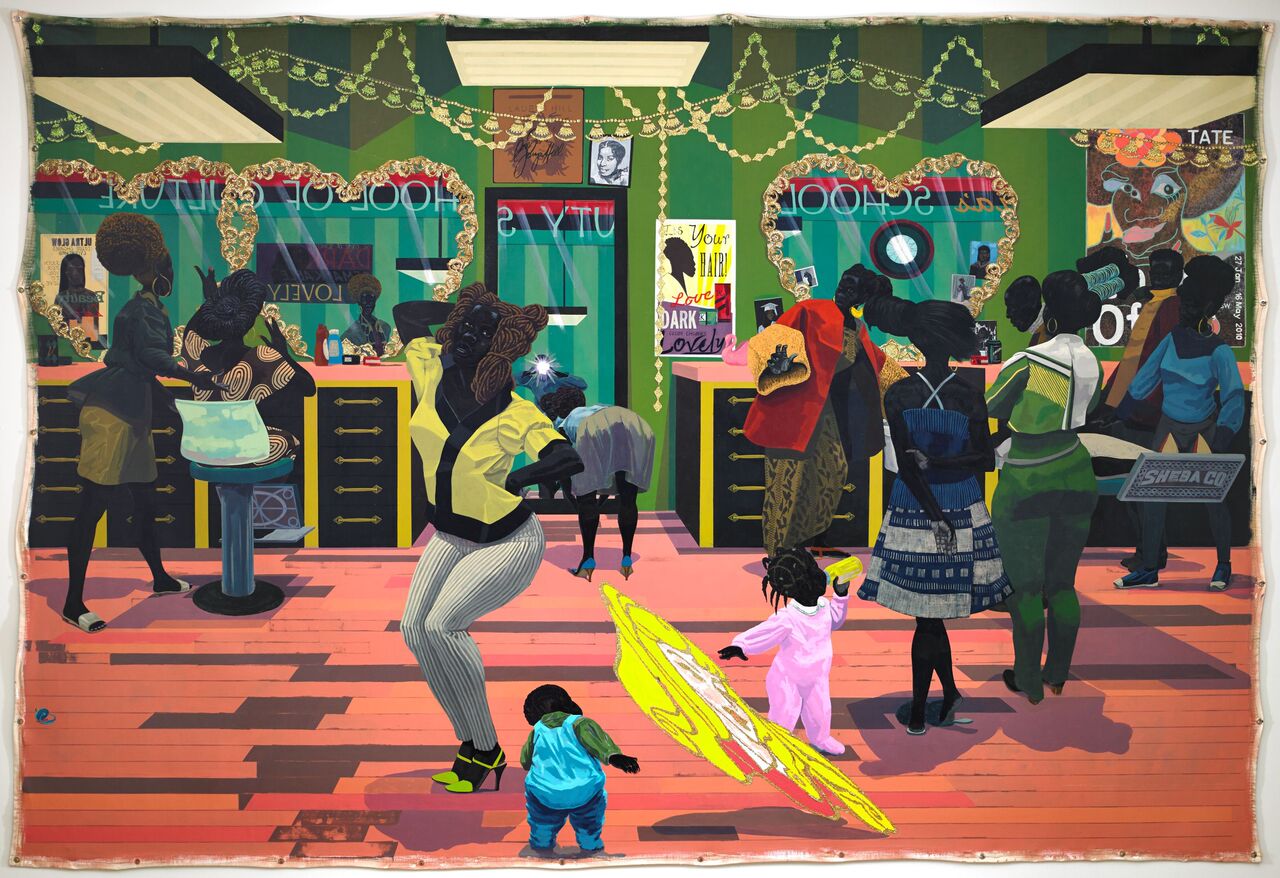

Kerry James Marshall, School of Beauty, School of Culture, 2012, acrylic and glitter on unstretched canvas, 107 7/8 x 157 7/8 in., collection of the Birmingham Museum of Art; Museum purchase with funds provided by Elizabeth (Bibby) Smith, the Collectors Circle for Contemporary Art, Jane Comer, the Sankofa Society, and general acquisition funds, photo by Sean Pathasema

The Black figure here is extraordinary, all-encompassing, demanding of our gaze. There is no distinction between the subjects’ shades: each person is painted a deepest black, deriding any possibility of shadism or self-hatred, removing any space for division or disconnectedness. There is only love amongst these subjects, and specifically Black love. We see this in the painting entitled School of Beauty, School of Culture – the children playing gently, women focused on hairstyling and beautification – and in a rendering of a Tate poster for the 2010 Ofili show with his Blossom painting featured (breast covered). The walls are simply filled with notions of celebration of self-love, a foretelling of Black love. And Marshall cleverly transforms the piece with his Holbein reference (The Ambassadors, 1533) to vanitas. At center stage, he includes a huge blonde-haired Sleeping Beauty and explains that “black women are haunted by the specter of white beauty embodied in Sleeping Beauty.” The reference is an uneasy one, because whilst the painting holds so much hope and elevation of Black forms of beauty, we are immediately brought back to the impact cultural determinism has on Black women.

Installation view of Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, March 12–July 3, 2017 at MOCA Grand Avenue, courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Brian Forrest

The retrospective’s most alluring and free form is the space where Marshall shares his collection of magazine and paper cuttings, the Baobob Ensemble (2003) in the Frederick and Joan Nicolas gallery. While you look through the scattered images of Black people in the center space, everything from Black Barbie to Benetton ads, there comes a warmth from the paintings surrounding you, as if this were your living room. The opulence in the room is pervasive and one feels free to look at the collected magazine cuttings but also feels watched by the surrounding gazes. This countering of “a lack in the image bank” of Black subjects as central actors in the media and other spheres is very powerful, and the paintings are a reflection of Marshall’s efforts to reverse this lack. This series of untitled works made in 2009 contain central black figures painting themselves without the colors required to paint their skin tone. It is a political commentary, but also a practical one, pointing out the scarcity of resources for Black artists across the board, from Black models having to do their own hair and make-up to Black actors being shot in lighting not complementary to their skin tones.

The color black is its own character in the show, such a dominant and repetitive motif that it becomes the norm here, much as Lucian Freud’s many-hued canvases saturate a room and make us reflect on the complexity of white skin color. Marshall explains that he’d been working towards achieving a black hue that had a complexity to it, and was not flat.

Installation view of Kerry James Marshall (Heirlooms and Accessories in the middle): Mastry, March 12–July 3, 2017 at MOCA Grand Avenue, courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Brian Forrest

The most powerful work, for me, is Heirlooms and Accessories (2002). Here Marshall does brilliantly what maybe Schutz could have done in her rendering of Emmet Till that gained so much notoriety at the 2017 Whitney Biennale. He sources a 1930s photograph of a lynching of two black teenagers, Tom Shipp and Abram Smith. He paints three of the white women spectators of the horrific scene, encasing each in an ornate brass painted locket. The sparkling gems that surround the frame remind us of the elevation and celebration of the use of violence perpetrated against Black people in the US in that particular era. It also foregrounds the safety that those willing spectators and perpetrators of the violence have within the legal and political systems of the US. The women in these three paintings are alert and excited by the prospect of witnessing the murder of two young black men; they remain anonymous and protected by the culture and social status that permeates US society.

Marshall is avowing that unless the “historical absence” is addressed directly – by the increased representation of the Black subject in the gallery/museum space – then one would be keeping intact “a kind of regime of representation that didn’t include enough people.” He expects the audience to engage with the intellect of the artist, that his art practice is a “communicative act, just like any other linguistic form.” “You want to be heard, you want to be understood, and you want a response that recognizes or demonstrates that you comprehend,” says Marshall. Making work that is inherently an intellectual activity is central to his mission. He wants the audience to experience the emotion and the beauty of seeing art, but fundamentally expects us to engage in an intellectual dialogue to understand his meaning within the work.

Kerry James Marshall, ‘The Mastry’ is showing at the Museum of Contemporary Art until July 3rd 2017.

Nan Collymore is a writer and ponderer. Materiality and embodiment are central to her work. She writes, programs art events and makes brass ornaments in Berkeley California. Born in London, she has lived stateside since 2006

More Editorial